"Put Back What You Use"

or

"I-Yi-Yi-Yi-Yi'm Not Your Stepping-Stone"

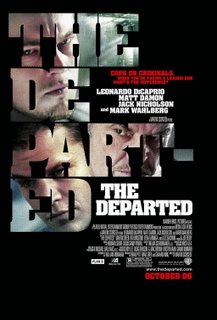

The family that preys together, stays together. For the extended family of boxer Micky Ward (Mark Wahlberg), the preying is mostly internal although they have the illusion that they're getting the best of everybody else.

Micky is the younger brother (step-brother, actually) of Dickie Eklund (Christian Bale), former up-and-coming boxer, who had one glory moment: knocking down Sugar Ray Leonard in a match some years before. Now, he's a part-time trainer for his half-brother and a full-time crack addict. HBO is making a documentary about Dickie, who, despite his years and habits, still thinks he's on the comeback trail. But the pipe keeps him missing training sessions with Micky, leaving the heavy lifting to his trainer (Mickey O'Keefe playing himself). While the boys' lioness of a mother (Melissa Leo) manages Micky and enables Dickie, it leads to some bad decisions on matches for Ward, leaving him battered and disillusioned. The higher-ups at the sports networks have Ward pegged as a "stepping-stone," the fall-guy they use to advance other fighters in the winning circle to boost ratings, and that reputation follows him around his home-town of Lowell, Massachusettes. Ward's on a downward spiral, and any outside help is treated with suspicion. "You can't trust that guy. He ain't family." says Dickie, lounging in the limo his brother's money rented, sucking a beer.

Yeah. About that...

Perspective is all in The Fighter. And the boxing motif is the perfect setting. Micky is caged by his relations with his family, but every time he tries to strike out on his own, he gets attacked by Mom (playing the suffering card), step-brother hangs back and then takes his licks, and a coven of sisters and half-sisters are a unified greek-chorus of mom-ditto-speak. All you need to make this a match is a soft canvas to fall on, so Micky's a fighter always on the defensive. It's no reason he doesn't say much, but the eyes are far away, looking for a way out, looking for an opportunity to make a move, looking for anything.

"Your fahther looks at my ass, too, but at least he tawks ta me," says Charlene (Amy Adams, while not looking at him), the "bah-girl" Micky keeps staring at. Micky's so down for the count, he thinks even she's out of his league. And she might be, but she keeps showing up in his corner, alarmed at the punishment he's taking. When she questions it, Micky tells her everybody's not concerned. "Who's 'everybody?'" she asks. "My mother, my brother," he replies.

Yeah. About that...The Fighter is a mostly true story. Ward is a better, tougher fighter than the movie wants to give credit for (the underdog status makes for a better story, I'm sure, but the dismissive commentary on the soundtrack during the fight sequences is the real thing...taken from the actual broadcasts...Ward was considered an underdog), and Dickie DID do all those things, but his timing was a bit better in real life. One wants to say that the best character arc in the movie is Dickie's, but that would be falling into the appreciation trap the movie sets up.

Because Micky's is the best character arc, although it seems a very simple Rocky-like success story on the surface. It's the approach that Micky takes with the forces in his life that are tearing each other apart which is the most interesting aspect of the story. Micky has been wronged by his family, but he won't discount their worth, or their place in his life, even over the objections of his new supporters—they have to find a way of dealing with each other and their conflicts, with or without him. For a fighter to take the stance that he does, reaching compromise with the warring factions in his life—to stand up and take control, risking everything from everybody—is a complete negation to what he does for a living and how he was raised.*The acting kudos are going to go to Bale (who is incredible, not to slight him) and Leo and Adams (who has two great scenes involving an intercom, and throws some nice punches in a chick-fight), but Wahlberg is the champ in this movie, with the tougher part (he trained for this through his last six roles), which he does almost purely physically. Micky is a man of few words, and not too many moods, but Wahlberg, restrained and less showy, does all of it with body language and does the difficult fight scenes, as well—in the latter taking a lot of body-blows that are not hidden with oblique camera angles or trickery. Wahlberg has worked with director David O. Russell before—in fact it was Russell's war pic Three Kings that first showed how good an actor "Markey-Mark" could be. Russell keeps the movie on edge with quick cutting and an improvised feel, even managing to make the final fight scenes nerve-rattling, despite the suspicion that one is going to see a typical boxing picture ending. But, his assurance with good material, performed by such a dedicated cast, manages to keep the movie on its feet, even at the final bell.

|

| Micky and Dickie at the time of the events of the film |

* The real-life Ward did much the same thing, often befriending his opponents, including Arturo Gatti, the fellow he boxed in his last three epic fights, often described as the greatest in the sport. Ward was a dedicated, fearsome fighter, but admired his opposites in the ring, and their talents. The two fighters, who put each other in the hospital, continue to be good friends. I find that amazing...and admirable.