or

Going For the Fences

You've got to hand it to Kevin Costner. He takes chances. He's parlayed his television success on "Yellowstone" to make a movie he's been dreaming of for a couple of decades, in times both fallow and flush, cast it with a steady stream of great character actors who've never passed onto the A-list, split it into two chapters (although hopefully there will be more) and released the first one—in which various story-lines do not intersect—as a 3-hour set-up...the sum of which would spell box-office poison to a movie-going audience that wants its product pre-digested and easily grasped like fast-food.

And who can blame him? He's done it before. When he was making it, Dances with Wolves was being derided as "Costner's Folly" for making a Western when they weren't fashionable, for it's extensive location shooting, for the supposed grandiosity of writing, directing, producing and starring in it, for it's planned use of sub-titles, and for its cost overruns.

But, as William Goldman wrote, nobody in Hollywood knows anything. Dances with Wolves became a box-office smash, its elegaic, and unconventionally seditious, story becoming a hit with audiences and garnering the Best Picture Oscar, beating out Goodfellas (which some may argue was a mistake, but, to my mind, really wasn't). So, here's "Coster's Folly" Chapter Two, the ungainly titled Horizon: An American Saga - Chapter 1, with a story by Mark Kasdan (who co-wrote Silverado, a favorite of mine), Costner and Jon Baird, photographed by J. Michael Muro, who shot Costner's lovely Open Range.

And it's great. Simply great.

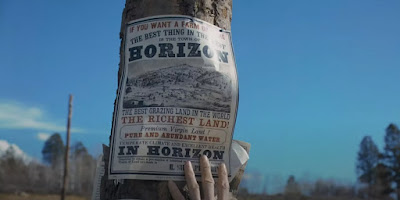

For a 3-hour movie, it sails right by, packed to the sprockets with detail, period and story-wise, never seeming to waste a frame in telling three...four? five?...stories about a plot of land in the San Pedro Valley in the American west that may—or may not —be available for homesteading, and the people who are attracted to the promise of it (whether it is true or not) and the people already living there who take it for what it is.

There are the first white settlers, there to survey and parcel, but as they're alone in the wilderness and, unbeknownst to them, surveying Apache hunting grounds, they soon fall victim to a war party. Their graves are the first semi-permanent structures of Horizon. They won't be the last.

But, the pattern will remain the same. By 1863, there is a well-established colony on the site, across the river from those three original graves. They, too, are attacked by Apache, leaving a limited number of survivors: some, like Frances Kittridge (Sienna Miller) and her daughter, Elizabeth (Georgia MacPhail) will take shelter at nearby Fort Gallant; others, like the boy who rode to the fort to get help, Russell (Etienne Kellici) form a hunting party to track down the Apache who burned down the encampment.

That attack has caused a dispute between the leader of the war party, Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe) and the leader Tuayeseh (Gregory Cruz), resulting in the younger man splitting from the tribe, taking one of Tuayeseh's sons with him.

In Montana, James Sykes (Charles Halford) is shot by Lucy (Jena Malone), who takes her son David and flees for the Wyoming territory. Sykes' sons Junior (Jon Beavers) and Caleb (Jamie Campbell Bower) are sent to find her and the child. They catch up with her where she now goes by the name Ellen, married to hopeful lands-trader Walter Childs and living with a local prostitute Marybelle (Abbey Lee). When the Sykes boys show up, there is a confrontation between the vicious Caleb and saddle-tramp Hayes Ellison (Costner), a potential customer of Marybelle's. She and Hayes and the child escape town to avoid repercussions of the murder.

Also heading for Horizon is a wagon train, moving along the Santa Fe Trail, under the auspices of Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson), who is having trouble keeping the eclectic group of settlers (including a naive British couple and the family of Frances Kittridge's late husband) of the mind that, although they may be headed for a paradise, they're not there yet, and water and team-spirit are in short supply in a desert.

In the mix are interesting characters, like the leaders of the Army detachment at Ft. Gallant, who are straight out of John Ford's Cavalry films: Lt. Trent Gephart (Sam Worthington, the most effective performance I've seen of his), who's a pragmatic soldier and would just as soon have settlers somewhere else and the "indigenous" (as he calls them) left to their land to keep the peace, a sentiment acknowledged but considered historically unrealistic by Gallant's leader, Col. Albert Houghton (Danny Huston) and his sergeant major, Thomas Riordan (Michael Rooker, in a slightly less garrulous version of the parts Victor McLaglan played in Ford films). One likes these people and you get the feeling everybody's doing the best they can under the conditions and the inevitability of time.

That's a novel's worth of people and a lot of stories and one suspects everybody's going to converge in Horizon (the town itself will probably end up being the focus of the series), their characters already established and with ensuing complications in the offing—Costner has previews of the next chapter at the end of this one and my appetite for it is whetted.

Despite the obvious nods towards Ford, Horizon: an American Saga, so far, feels more in the vein of the sprawling How the West was Won, but, in character, more like "Lonesome Dove", where individuals weave in and out of the fabric of the narrative, and sometimes—as in life—are never to be seen again in an indifferent Universe, lost in the stream of History. Costner may love his Westerns, but he acknowledges there's less romanticism to it when the survival rate hovers around 50%.

It was in Ford's film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, where a reporter states "This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." Ford's career peeled back veneers of western legend varnish in his films and in his later work stripped off more layers of his own earlier myth-making. Costner goes even farther, taking into account the grubbier myths of Leone and Peckinpah (and Eastwood) with his hard-scrabble porous towns in need of light and cleaning and extermination. He goes a step further by putting back all the practicalities of the settler experience that Ford cut

out—the burying of the dead, the scarcity of water, the bugs

and critters, the difficulty of killing a man with ball-shot, the necessity of self-sustainment by farming, the ritual of hard work, more important community matters than tea-dances and ceremonies.

If there's anything more to wish for, for me, it would be that there's more of it (despite others quibbling about length). A couple transition sequences seem to have been excised just to speed things along that might not have added much but may have smoothed a passage of time.

No comments:

Post a Comment