or

"Time Sure Does Fly, Doesn't It?" ("And Then I Blink...")

I kept thinking of Robert De Niro in The Deer Hunter while watching Here, the latest film by director Robert Zemeckis.

"One shot." "One shot."

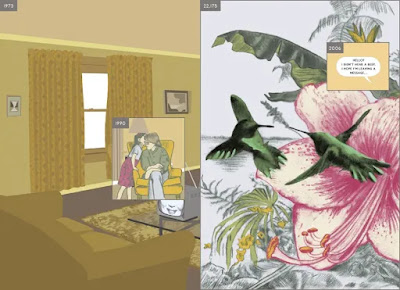

Which is what Here is. Based on a graphic novel* (by Richard McGuire, which is done the same way), the film eliminates the one major creative decision for a director—"where do I put the camera?"—and takes it, literally, out of the picture. Zemeckis, as a director, is a weird cat. Where a lot of directors will look for thematic material and then build the technical aspects around it, Mr. Z seems to think of the technical challenge first and then find the story to fit it. He was ground-breaking in making mo-cap animation films and as the Uncanny Valley started to get flooded with product so that nobody could see it any more, he started to trust the CGI with drama. It can be done. But, as amazing as Zemeckis' films can look, they sometimes have the heart of a demonstration disc. Inspiration but not aspiration.

So, here's Here. And, technologically, it is pretty amazing, but for reasons that have nothing to do with story-line (except in some nicely worked-out places) or the fact that it re-teams Tom Hanks and Robin Wright nostalgically from Forrest Gump. They are basically irrelevant other than box-office draw (frankly, I was more intrigued to see Kelly Reilly—from "Yellowstone" and the Downey Jr. "Sherlock" movies—and Michelle Dockery—from "Downton Abbey"—in it. It's not a movie where you can judge performances, scattered as they are in this movie's timeline.And the incidences feel like snap-shots—or worse, like "Saturday Night Live" skits—they pop up, do a bit of business and generally exit on a laugh or a dramatic hit ("And...scene"). God forbid that they should interrupt one of those slices-of-life in mid-chaos and have it resolve later in the story. That would have felt random, instead of calcified and calculated as this movie too-often feels like.It starts out with its gambit efficiently enough—that one angle—whether it's in a house on that particular parcel of real estate or in its origins as primordial ooze when the boxes start fading in, initially with subtle borders around them until we get the knack of it and then those borders start fading away and they begin to make transitions so we see the neighborhood go from dinosaur stomping ground to hellish landscape to ice age (only one of two times when the camera actually moves) to Native American habitat to the neighborhood of William Franklin (Benjamin's ever-loyal-to-the-king non-rebellious son) to the story-heavy 20th century. The Franklins' eventual neighbors are The Harters (he's excited that an "aerodrome" will be built nearby and intends to fly—something his wife is dead-set against); there's the bohemian Beekmans, she's a free-spirit and he's an inventor, perfecting a chair he calls the "Relaxo-boy"; post WWII, the non-surnamed folks we'll spend most of the time with (let's call them "The Gumps") move in, sail through the 50's and television, raise Tom Hanks, who gets his girlfriend Robin Wright pregnant, they get married and move in with the folks and eventually age out of the house; then we get the Harris', the only minority couple—besides the Native Americans—that reside there. We get nudged a lot about how things change—the Harris' give their son "The Talk"—and not—frailty and death are inevitable, as apparently is influenza.

For the most part, these folks are chess-pieces that get moved around depending where the boxes show up and those boxes highlight the transitions between entertainment systems, gas-lights to electric, rugs versus hardwood (versus verdant forest), couches to sectionals. Art changes, but the view rarely does. Dramatically, the film underwhelms except in some key places. But, it's not a waste of time...or space. Not at all.We are used to being manipulated in movies by mise-en-scene and blocking. Directors let us see what they want us to see and use blocking to change the focus of our attention. This gives us the illusion that we're peeping through a letter-boxed slot-view a 360° world-view (we're not, of course; it's an illusion). Here subverts that. We are given one angle to look at—the world may change within it, but it's basically that one section of cinema real-estate, like we're looking at the Closed Circuit Camera of Eternity.

So, here's Here. And, technologically, it is pretty amazing, but for reasons that have nothing to do with story-line (except in some nicely worked-out places) or the fact that it re-teams Tom Hanks and Robin Wright nostalgically from Forrest Gump. They are basically irrelevant other than box-office draw (frankly, I was more intrigued to see Kelly Reilly—from "Yellowstone" and the Downey Jr. "Sherlock" movies—and Michelle Dockery—from "Downton Abbey"—in it. It's not a movie where you can judge performances, scattered as they are in this movie's timeline.And the incidences feel like snap-shots—or worse, like "Saturday Night Live" skits—they pop up, do a bit of business and generally exit on a laugh or a dramatic hit ("And...scene"). God forbid that they should interrupt one of those slices-of-life in mid-chaos and have it resolve later in the story. That would have felt random, instead of calcified and calculated as this movie too-often feels like.It starts out with its gambit efficiently enough—that one angle—whether it's in a house on that particular parcel of real estate or in its origins as primordial ooze when the boxes start fading in, initially with subtle borders around them until we get the knack of it and then those borders start fading away and they begin to make transitions so we see the neighborhood go from dinosaur stomping ground to hellish landscape to ice age (only one of two times when the camera actually moves) to Native American habitat to the neighborhood of William Franklin (Benjamin's ever-loyal-to-the-king non-rebellious son) to the story-heavy 20th century. The Franklins' eventual neighbors are The Harters (he's excited that an "aerodrome" will be built nearby and intends to fly—something his wife is dead-set against); there's the bohemian Beekmans, she's a free-spirit and he's an inventor, perfecting a chair he calls the "Relaxo-boy"; post WWII, the non-surnamed folks we'll spend most of the time with (let's call them "The Gumps") move in, sail through the 50's and television, raise Tom Hanks, who gets his girlfriend Robin Wright pregnant, they get married and move in with the folks and eventually age out of the house; then we get the Harris', the only minority couple—besides the Native Americans—that reside there. We get nudged a lot about how things change—the Harris' give their son "The Talk"—and not—frailty and death are inevitable, as apparently is influenza.

For the most part, these folks are chess-pieces that get moved around depending where the boxes show up and those boxes highlight the transitions between entertainment systems, gas-lights to electric, rugs versus hardwood (versus verdant forest), couches to sectionals. Art changes, but the view rarely does. Dramatically, the film underwhelms except in some key places. But, it's not a waste of time...or space. Not at all.We are used to being manipulated in movies by mise-en-scene and blocking. Directors let us see what they want us to see and use blocking to change the focus of our attention. This gives us the illusion that we're peeping through a letter-boxed slot-view a 360° world-view (we're not, of course; it's an illusion). Here subverts that. We are given one angle to look at—the world may change within it, but it's basically that one section of cinema real-estate, like we're looking at the Closed Circuit Camera of Eternity.

That's where McGuire's boxes come in. Yes, blocking will direct the eye, but it's those moving boxes and their shifting perspectives through time (but not space) that directs your attention, whether it's what's on the television screen, or the silhouette of the car (or buggy) going by the window. Transitions flash in the wink of an electrical storm or a camera flash. Things shift, warp, grow their hair out and stoop but only for a moment of time. If only to have The Beatles on Ed Sullivan accompany the wedding shot (see below).And—as with McGuire's work—that's the point it's making. Life seems long. But, in the scope of things, it's transitory, gone in the blink of an eye. And that little plot of space we inhabit will still be there, long after the seas rise, the epidemics cull us, idiots atomize us, and we're just dust. Like George Carlin said "Earth Day?! The Earth will be FINE! WE'RE screwed!" Enjoy the details, the movie seems to tell us. We're just passing through.A couple of shots—little clever instances I liked. The one below, which is the only time we see the rest of the main floor courtesy of a moved bureau.

And this one haunts (and pays a little respect to the McGuire work): while Paul Bettany's "Dad" sleeps on the couch, a box appears to show an earlier version of his long-since-passed wife (Reilly) and she says the first words of McGuire's graphic novel: "Hmm. Now why did I come in here again?" That raised goose-bumps.

It's an interesting experiment for a movie that somebody might come up with a dramatic reason to exploit. But, the point's been made. Like the guy who invents the La-Z-Boy you have to ask yourself—what's it good for?

And this one haunts (and pays a little respect to the McGuire work): while Paul Bettany's "Dad" sleeps on the couch, a box appears to show an earlier version of his long-since-passed wife (Reilly) and she says the first words of McGuire's graphic novel: "Hmm. Now why did I come in here again?" That raised goose-bumps.

It's an interesting experiment for a movie that somebody might come up with a dramatic reason to exploit. But, the point's been made. Like the guy who invents the La-Z-Boy you have to ask yourself—what's it good for?

* McGuire's work is so seminal and so tied to the film's strategy—and expanded to different platforms—that the Zemeckis film is almost unnecessary. It started out in 1989 as a 6 page story in Raw Volume 2 #1:

The original's time-frame is from 500,957,406,073 BC to 2033 AD

In 1991, the story was adapted into a student film by Timothy Masick and Bill Trainor, students at RIT's Department of Film and Video.

In 2014, McGuire expanded "Here" into a 304-page graphic novel with vector art and watercolors and extending the timeline from 3,000,500,000 B.C. to A.D. 22,175:

That would be a herculean jump enough, but the Ebook addition of "Here" allowed you to scroll between pages with animated gifs inserted. Which is mind-blowing enough, but at the 2020 Venice Film Festival, a VR version of it was presented.

See what I mean about the 2024 movie being "unnecessary"—it feels like, artistically and technologically, we've already moved beyond it.

No comments:

Post a Comment