"More Human Than Human"

or

"If We Could Talk to the Animals (Speaking to a Chimp in Chimpanzee)"

or

"If We Could Talk to the Animals (Speaking to a Chimp in Chimpanzee)"

"It was the 70's...," says one of the interviewees in Project NIM, as if in explanation.

"It was the species," says I, looking for my tranquilizer gun.

The new film by Man on Wire

For just as Man on Wire is a study of hubris and the arrogance of man (which results in a marvelous, magical thing), Project NIM does the same thing, while showing just how lousy human beings are, even with the best (or most curious) of intentions. We meet a lot of talking heads in Project NIM and few can be considered the best examples of our species to teach another anything. In fact, Project NIM is more of a study of human behavior than it is anything to do with monkeys'.

The guy who devises the study is Dr. Herbert Terrace (after Project Washoe which was an earlier, more disciplined study and was more convincing of anecdotal evidence), and one wonders what his motivations are, besides the obvious personal ambitions of getting attention and using it as a means of attracting young interns.** The first person to raise NIM is Stephanie, a self-described "hippie-chick," and it's a mystery that Terrace picked her to be the initial teacher for NIM, as she had no desire to keep notes and records, did not know sign language, and eventually grew impatient with all the insistence on "process," preferring to just interact with NIM as a member of her family. Terrace makes some comment about her being a "warm" "empathetic" person and then drops the bomb that the two had had a previous "relationship," (which will prove to be a common—all-too common—theme throughout the documentary, as the humans seem more concerned with "hooking up" than concentrating on their charge—"it was the 70's, after all" says one laughing). Eventually another trainer is found for NIM, Laura-Ann, and it's readily apparent that there is no love lost between her and Stephanie, as some mutual passive-aggressive sniping occurs between the two. Laura-Ann is much more successful in teaching sign to NIM (Stephanie says on-camera "Words are a fucking nightmare to communication..." which makes one wonder about her qualifications even more) and the chimp's knowledge of ASL increases at a fast clip. Terrace and she also begin "a relationship," just as two other therapists begin working in the study. Also, at this point, Terrace steps out of the day-to-day monitoring, that is, unless a camera shows up for a photo op, or a news-story, and there are some amusing out-takes of Terrace trying to handle NIM, but being quite incapable of it. "Herb Terrace was an absentee landlord" grouses one of the researchers.It becomes readily apparent in Marsh's timeline and necessary compression of the events that the humans were far more concerned with their own lives, and that, however much affection and wonder is expressed at NIM's progress, he is little more than an amusing lab-rat, albeit one you can talk to about food. And, as with "Frankenstein," pretty soon the subject of the study is considered less valuable, and, ultimately, disposable.

It cannot end well and it doesn't, even with the best of intentions, and the heroes of the story, if there can be any, come from the most unlikely of places. What I find amazing is that Marsh, as he did with Man on Wire, can coax such naked honesty in a documentary that makes the researchers look like such creeps. Philippe Petit, the subject of Man on Wire came across as something of a jerk, but his accomplishment was so amazing one could forgive his idiosyncrasies and foibles. These men and women have no such stunts to hide behind, and although they may act like the end justifies the means, in the end, they simply abandoned a project and left the life they'd altered on its own, not quite chimp, not quite human. That ivory tower looks a little less spotless in the aftermath.

Makes one wonder if this evolution "thing" is all it's cracked up to be, given the evidence.

|

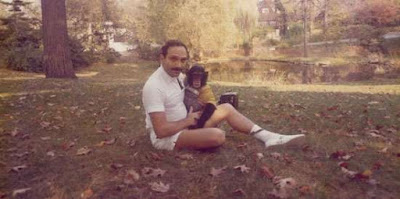

| Two of "the good guys"—Bob Ingersoll and Nim Chimpsky |

** I seem to be coming down hard on Terrace ("That's DR. Terrace..." he says at one point in the film), but he comes across as smug, arrogant...and a tad clueless in Marsh's film (Don't these folks know how they're going to come off?). Also, slightly retributive. After his slap-dash study—heavy on the personal agenda—ends he writes a book about the study saying "Nah...chimps don't use language because they have no syntax"—merely parroting words they've been taught to get what they want, without proper sentence structure, or tense. True. It's the same way I communicate with my dog, Smokey. We pick up on each other's "cues" of behaviors and words we recognize and respond appropriately. For example, if I command my dog to go to the bathroom (he does this by suggestion) and he doesn't "have to go," he'll simply sit. Which tells me "No, really, it's not necessary. How about a cookie, though?" NIM was doing this with his trainers and with other apes...and taught other apes basic ASL (shades of Planet of...), just as he communicated with ape-cues to other apes. The thing that struck me about NIM (which I remember from some of the docs made when the study was going on), was that he learned to curse. If he got mad at something, he'd make the sign for "Dirty," which was related to his toilet training. Nobody taught him that "Shit!" was an expression of frustration. He came up with that on his own. Explain that.