I don't like those: they're rather arbitrary; they pit films against each other, and there's always one or two that should be on the list that aren't because something better shoved it down the trash-bin.

So, I came up with this: "Anytime" Movies.

Anytime Movies are the movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, sometimes it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again (and again!) and never tire of them. There are ten (kinda). They're not in any particular order, but the #1 movie IS the #1 movie.

What's George Lucas' best film? For most, it's probably Star Wars (I'm sure there's some poor soul out there who likes Radioland Murders). There's a lot to like about his charmingly scruffy homage to the Buck Rogers serials. But one wonders what direction his career might have gone if he hadn't felt the need to exploit that first "Star Wars" movie as much as he did. It seems the more he explained about his initial concepts the worse the movies got, and the more rich and famous they made him, the more elephantine and fossilized they became.

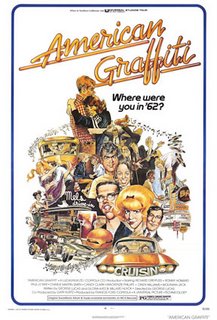

What's George Lucas' best film? For most, it's probably Star Wars (I'm sure there's some poor soul out there who likes Radioland Murders). There's a lot to like about his charmingly scruffy homage to the Buck Rogers serials. But one wonders what direction his career might have gone if he hadn't felt the need to exploit that first "Star Wars" movie as much as he did. It seems the more he explained about his initial concepts the worse the movies got, and the more rich and famous they made him, the more elephantine and fossilized they became.For me, Lucas has yet to top American Graffiti. Made for under a million dollars and filmed mostly at night using a skeleton crew (albeit one headed by Haskell Wexler), it showed just how ingenious Lucas could be when he was strapped for cash. It has the structure and froth of a Shakespeare comedy with the values and budget of an AIP teen flick. Seemingly aimless, American Graffiti follows four storylines of small town kids on the last night of summer before heading to college. Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) has a scholarship to a big university but is reluctant to go, and spends the night bounced around by local toughs, and diverted by his quixotic pursuit of a phantom blonde in a white Thunderbird. Steve and Laurie (Ron "Ronny" Howard and Cindy Williams) are a couple in transition. Class President and Head Cheerleader, they're the Royal Couple of the Sock-Hop. But Steve can't wait to head out of town to conquer new territory, and Laurie-still in high school-knows she'll lose him when he goes. John (Paul LeMat) is a high school drop-out and legendary hot-rodder endlessly cruising the streets of town, looking for the next race. And Terry (Charles Martin Smith) lives a rich fantasy life (that's a kind way of saying he's deluded) where he can imagine himself everything that he's not.

|

| The Village Square |

In the background are the constant echoes of rock n' roll pouring out of car windows and reverberating down the hallways and back-alleys, broken only by the howls and shrieks of the common thread in their lives, Wolfman Jack. All the kids have their Wolfman myths and he acts as sage, seer, siren and Master of Ceremonies for the evening's adventures. He's also the Fool and "The Man Behind the Curtain." Ultimately the long night's journey leads to his door-step, and, in disguise, dispenses his wisdom to the seeker.

|

| The Siren |

|

| The Knight-Mentor |

The Trailer for "American Graffiti"--in the style of Beach Blanket movies

I'd just done a "Don't Make a Scene" segment for American Graffiti and was looking forward to writing new "insights" on this film, but reading it again, no, I pretty much covered them all. Not that American Graffiti is that simple—it's just that given Lucas' skimpy out-put, there's not a lot of complexity in his ouvre. It is interesting that Lucas goes the Joseph Campbell route in this film before he actually read "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" and used the "seeker's path" for the construction of Star Wars. He was already using it here and doing variations of it for the four Lucas-aspects, each with different fates (a cautionary tale, indeed). He also uses the cross-cutting on different fronts that would be his staple in the "Star Wars" films, but interestingly in his first Star Wars (A New Hope) and this film, there is no cross-cutting at the end, everyone is melded into the final story-line, buttoning everything up nice and neat.

He wouldn't do that again.

American Graffiti

To Kill a Mockingbird

Goldfinger

Bonus: Edge of Darkness

Scout(reading): "I had two cats... which I brought ashore... on my first raft. And I had a dog."

Scout(reading): "I had two cats... which I brought ashore... on my first raft. And I had a dog."

Scout: Atticus, do you think Boo Radley ever really comes and looks in my window at night? Jem says he does. This afternoon when we were over by their house...

Scout: Atticus, do you think Boo Radley ever really comes and looks in my window at night? Jem says he does. This afternoon when we were over by their house... Atticus: Scout...I told you and Jem to leave those poor people alone. I want you to stay away from their house...and stop tormenting them.

Atticus: Scout...I told you and Jem to leave those poor people alone. I want you to stay away from their house...and stop tormenting them. Scout: Yes, sir.

Scout: Yes, sir. Atticus: That's all the reading for tonight, honey. It's getting late.

Atticus: That's all the reading for tonight, honey. It's getting late. Scout: May I see your watch?

Scout: May I see your watch?

Scout: "To Atticus, my beloved husband." Atticus, Jem says this watch is gonna belong to him someday.

Scout: "To Atticus, my beloved husband." Atticus, Jem says this watch is gonna belong to him someday. Scout: Why?

Scout: Why?

Atticus: Well... it's customary... for the boy to have his father's watch.

Atticus: Well... it's customary... for the boy to have his father's watch. Scout: What are you gonna give me?

Scout: What are you gonna give me?

Atticus: I don't know that I have much else of value that belongs to me.

Atticus: I don't know that I have much else of value that belongs to me. Atticus: But there's a pearl necklace, there's a ring that belonged to your mother. I put them away, and they're to be yours.

Atticus: But there's a pearl necklace, there's a ring that belonged to your mother. I put them away, and they're to be yours.

Atticus: Good night, Scout.

Atticus: Good night, Scout. Scout: Good night.

Scout: Good night.

Atticus: Good night, Jem.

Atticus: Good night, Jem.

Scout: Jem?

Scout: Jem? Scout: How old was I when Mama died?

Scout: How old was I when Mama died? Scout: Was Mama pretty?

Scout: Was Mama pretty? Scout: Was Mama nice?

Scout: Was Mama nice? Scout: Did you love her?

Scout: Did you love her?