I don't like those: they're rather arbitrary; they pit films against each other, and there's always one or two that should be on the list that aren't because something better shoved it down the trash-bin.

So, I came up with this: "Anytime" Movies.

Anytime Movies are the movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, sometimes it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again (and again!) and never tire of them. There are ten (kinda). They're not in any particular order, but the #1 movie IS the #1 movie.

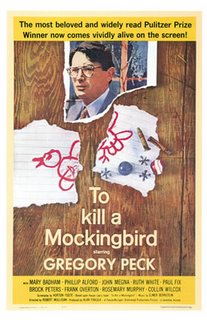

What is it about this film that puts it on so many favorites lists. Horton Foote’s masterful telescoping of Harper Lee’s frail, powerful novel? The fact that, as movie adaptations go, this is certainly one of the best? That it has an impeccably picked cast, directed to feel absolutely real, including three of the best child-performances in all of movies, by one of the best directors of actors, Robert Mulligan? The beautiful, fragile score by Elmer Bernstein, certainly contributes.

What is it about this film that puts it on so many favorites lists. Horton Foote’s masterful telescoping of Harper Lee’s frail, powerful novel? The fact that, as movie adaptations go, this is certainly one of the best? That it has an impeccably picked cast, directed to feel absolutely real, including three of the best child-performances in all of movies, by one of the best directors of actors, Robert Mulligan? The beautiful, fragile score by Elmer Bernstein, certainly contributes.I remember seeing To Kill A Mockingbird when I was seven years old, and not “getting it” much. I remember being annoyed with my Mom for trying to cover my eyes during the “scary” parts—although Robert Duvall as “Boo” Radley did genuinely creep me out back then (in fact, he still does, a bit). I didn’t “get” the dog-shooting (“He won’t kill a mockingbird, but he’ll sure-as-shootin' kill a dog!”) But I remember that it was a scary movie for a kid. In the film, the night was so dark, and any light cast spooky elongated shadows and trees moved and leaves rustled. The World seemed restless and alive when it should have been still and asleep. It was a world that, under the pretense of peace and calm, seethed with menace and dread just under the surface.

And that’s the key, I think. There seemed to be, in the movie, at least, a sense that the tremulous world was lurching and struggling to change—that the very earth was metamorphosing and demanding it, while the people entwined in that world, moved along, oblivious to the change, holding onto a complacent life that would inevitably end. At the same time, Mockingbird has the feel of nostalgia—the palpable sense that life flows through our fingers like sand, and that we’re always in danger of losing that life we hold precious.

But you don’t think of these things when you’re a child. Summers are endless. Life is eternal. If born into a nurturing, protecting household (and that is key) there is the illusion that the world is benign and all things are possible…under heaven.

Like integrity.

Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) awaits a lynch-mob, that first to his initial dismay

and then wonder is shamed and turned away by his own children. He shouldn't have wondered.

and then wonder is shamed and turned away by his own children. He shouldn't have wondered.

When the American Film Institute held a vote for the cinema’s best hero, the honor did not go to the Sergent Yorks or the Skywalkers or the Bonds or any of the roles played by Eastwood, Willis or Schwarzenegger. It went to a character of gentle heroics who in the course of the movie only fires one shot, who does not raise a hand in anger, and with jaw set and quiet voice does what he knows to be right. It was a shock that Atticus Finch would be voted the greatest movie hero, but it was the best choice possible, and legitimized the idea of holding such a silly poll in the first place.

Stephen Frankfurt's evocative title sequence.

Music by Elmer Bernstein

Horton Foote died March 4th, 2009. Director Robert Mulligan died right before Christmas, 2008. William Windom, in 2012. Brock Peters died in 2005. Peck, in 2003. My favorite actor in this and many things, Frank Overton, died in 1967. Survivors are Robert Duvall (Arthur "Boo" Radley), Rosemary Murphy ("Miss" Maudie Atkinson), and the Finch kids.

And Harper.

Except for her one gentle novel that stood like a golden spike in the Civil Rights Era, Nelle Harper Lee has published no other novels, only a scattering of essays. Not a recluse, she merely avoids the public spotlight. She, in her shy ways, does no public speaking. She has said what she is going to say. And that should be enough.

Harper endures.

Afterword: Harper Lee died on February 19, 2016, shy of her 90th birthday. Her agent published her first novel "Go Set a Watchman,"-the rejected first novel that inspired her editor to tell her to "write about the kids"

To Kill a Mockingbird

Goldfinger

Bonus: Edge of Darkness

No comments:

Post a Comment