|

| The first "Peanuts" strip: a punch-line with a palpable punch |

Like a Warm Puppy

or

Keeping the Grief Good, Charlie Brown

So, there's two "Peanuts" (or "Peanutses"). There's the strip that Charles M. Schulz created that created the sensation, and then there's "the sensation"—the more positive, merchandisable version that adorns Hallmark cards and is "Peanuts"-lite, full of soft-ball aphorisms and "warm puppy" thoughts. It's the "Peanuts" of the TV specials—"A Charlie Brown Christmas" and the like. Schulz had creative control over those, just as he did over the strips. But, he made the "Tube"-"Peanuts" less tragic, less biting, and less mean.

And less meaningful.

The new Blue Sky production of The Peanuts Movie is like those—you can tell by the music and the call-backs (check out when the kids dance) to those earlier hand-drawn cartoons. Charlie Brown is the perpetual loser, but in the end, he is celebrated and "has his day." In the strips, the only time Charlie Brown had a triumph was when he got a rash that made his round head look like a baseball and he started wearing a paper sack to cover it up. All of a sudden, he was looked up to as a sage and a more respectable person (and isn't that a commentary on how perception and "worth" are controlled by pre-conceived notions and looks?).

|

| AAAAUGH! |

|

| The Charlie Brown POV |

|

| A "Chuck Jones" moment |

|

| "Our hands touched, Chuck" |

|

| You Blockhead! |

He was nicknamed “Sparky.” He taught me how to read. He taught me what was funny. He probably had more than a hand in making me appreciate suffering and melancholy.

And he always made me laugh. He still does. One of the great joys in snatching up the new publications of “The Complete Peanuts” is to see the early, humbly ground-breaking work of Charles M. “Sparky” Schulz—his gentle skewering of life and ideas in Eisenhower-era America-a kind of combination of "The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit" and “The Button-Down Mind” dressed in shorts and penny-loafers. The consistent chagrin of Charlie Brown at another talent un-achieved. The constant harpiness of Lucy that ever expanded into inventive new areas of abuse. Linus, the intellectual, who, although he always had a fact or a scripture quote at the ready, still depended on a security blanket. Schroeder-an obsessive compulsive deifying Beethoven to the point he can play classical pieces on a toy piano. Schulz’s kids were doomed to be seen from two angles only: straight-on or profile--like a “wanted” poster. They walked six inches above the ground at all times. Linus’ little cult of “The Great Pumpkin” turned religion and the pageantry of Christmas on its materialistically-tinseled ear. The complete neuroses of these little losers that, of course, turns the dog to flights of fancy. You’d escape, too, if your lemonade stand had been replaced by a “psychiatric booth.” (“5¢ The Doctor is In”)

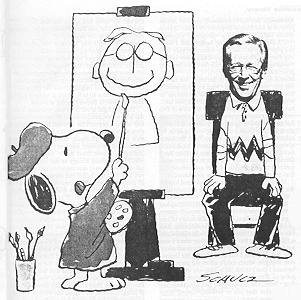

It became the norm (I was going to say fashionable, but that takes some effort) to simply dismiss Schulz and his work. You couldn’t ignore him, he was everywhere—TV specials, greeting cards, Macy’s Parade balloons, hawking Dolly Madison sugar snacks and Met-Life Insurance. Al Capp once wheezed that Schulz was the only man in history who made a fortune selling “clean” postcards. Schulz’s scribbles made him a multi-millionaire with a big skating rink as his own private Xanadu. It’s easy to look at all that and discount the work he was doing. Anything that popular, so universally received, couldn’t be of any REAL value, could it? And sure, he could play it safe. But the basic concepts of “Peanuts” (he hated that name—it was the idea of a publisher) are bizarre. We just grew used to them. And then we took them for granted.

The fact that Schulz, day after day, faced his white cardboard and created a strip six days a week with an expanded Sunday strip by himself with no assistants for nearly 50 years is an amazing achievement (something that is endlessly written about in the links below). That he could still go to that well-spring of creativity and come up with fresh concepts with the exquisitely-timed four panels of his strip makes him that much more inspiring than his contemporaries. Trudeau couldn’t do it. Breathed, Watterson, Larson—they all quit, fearing the dreaded “staleness” that Schulz—humble Charlie Schulz—nimbly avoided for nearly half a century. And his ambitions were rather small: a good quality gag, a fine ink line.

The strip was so much a part of the man and the man the strip, that he only retired, very reluctantly, when he feared he was dying. And when the nation heard that he was hanging it up, it was like somebody pulled a football out from under them. Suddenly, the book collections that stopped being printed every year like clockwork, reappeared. There was a crush for interviews. Tributes were made. At the end of it, Schulz saw just how relevant he was. That must have meant something very special for him in his last days. Or he might have seen it as another “Peanuts” irony, hung his head against a brick-wall and said “Augh!” For me, there is something awe-inspiring and just a little sacred that on the eve of the publication of his very last original strip, Schulz died in his sleep. When his creation ended, so did he. And it outlasted him just a little bit. From a lifetime documenting the frustrations and heart aches of failure, he got that one exactly right. But then, Schulz’s timing, comic and ironic, was always perfect.

Among the links below are some of those last tributes, and I’ve included Art Spiegelman’s rather cold (and admiring) analysis of the man and his work. Plus, there’s my favorite strip of his…at least today’s.

No comments:

Post a Comment