Well, Nobody's Perfect

Samuel "Billy" Wilder was born June 22, 1906 in Sucha, Galicia, Austria-Hungary ("with a brain full of razor blades" as Jack Lemmon remarked, admiringly). His father, Max, ran a cake shop in Sucha's train station, expanded into several cafes and moved to Krakow to run a hotel before settling in Vienna. Instead of attending University, young "Billie" became a journalist and, interviewing bandleader Paul Whiteman, traveled with the jazz great to Berlin, where he worked as a taxi dancer in the city's Eden Hotel, then a newspaper stringer specializing in sports and crime reporting.

Samuel "Billy" Wilder was born June 22, 1906 in Sucha, Galicia, Austria-Hungary ("with a brain full of razor blades" as Jack Lemmon remarked, admiringly). His father, Max, ran a cake shop in Sucha's train station, expanded into several cafes and moved to Krakow to run a hotel before settling in Vienna. Instead of attending University, young "Billie" became a journalist and, interviewing bandleader Paul Whiteman, traveled with the jazz great to Berlin, where he worked as a taxi dancer in the city's Eden Hotel, then a newspaper stringer specializing in sports and crime reporting.

During his reporter days, Wilder tried writing screenplays, producing films between 1929 and 1933, working with other young directors like Robert Siodmak and Fred Zinnemann. When Hitler became chancellor, Wilder fled to Paris where he wrote and co-directed (although star Danielle Darrieux confessed that Wilder's co-director was barely on-set) his first film, then immigrated to Mexico and, after the required six months (where he learned English), the United States, where his career as a screenwriter took off, earning his first Academy Award nomination (with partner Charles Brackett) for Ernst Lubitsch's Ninothcka. A subsequent script, Ball of Fire, saw Wilder diligently attending the filming and studying the techniques of director Howard Hawks. Hawks' mentorship allowed Wilder the "insider's knowledge" and "set-time" to demand that he direct his scripts from thenceforth.

Wilder tells the story—whether apocryphal or not, it doesn't matter—of having to re-enter the U.S. from Mexico after his six month work-visa ran out. "I've often told this story, about waiting in the consul's office in Mexico, hoping and praying the guy would show me some pity, and let me back into the U.S. The guy asked me for my papers—all I had was a passport and a birth certificate and some letters I'd gotten from Americans who vouched for the fact that I was honest...So I was truly at his mercy."

"So this guy asks me, 'What do you do professionally?' And I tell him I write movies. He says 'Is that so?' He gets up and paces up and down and then behind me, I guess he was measuring me, something like that. Comes back to his desk, picks up my passport, takes a rubber stamp and he stamps it! Then he hands it back to me, and says 'Write good ones.'"

"God bless the guy. Never knew his name, he was just an assistant or something, but I've spent the rest of my career trying to write good ones for him."

Mauvaise Graine (aka "Bad Seed")("co-directed" with Alexandre Esway, 1934) To hear star Danielle Darrieux say it, Esway was never on-set—he was an established director, and his name was used when Wilder (on the run from Nazi Germany) and some fellow ex-patriates filmed this cobbled together screenplay (the title translation is "Bad Seed") about car thieves in Paris. Rich scion Henri Pasquier (Pierre Mingand) has his "wheels" sold out from under him by his disapproving doctor-father (who had bought the car for him, anyway). What's a boy with a playboy lifestyle to do? Steal it back, of course! But, his crime is seen by three toughs in another car and after a frenetic car chase, Henri is stopped and told to follow them to a secreted garage—the hub of a car-stealing ring. At first, he's grilled to see if he's part of a rival gang, but when he explains the situation, his skill is looked upon highly enough to be asked to join. He then hooks up with fellow thieves Jean-La-Cravatte (Raymond Galle) and his sister Jeanette (Darrieux), who serves as a distraction for potential thievery victims.

Wilder tells the story—whether apocryphal or not, it doesn't matter—of having to re-enter the U.S. from Mexico after his six month work-visa ran out. "I've often told this story, about waiting in the consul's office in Mexico, hoping and praying the guy would show me some pity, and let me back into the U.S. The guy asked me for my papers—all I had was a passport and a birth certificate and some letters I'd gotten from Americans who vouched for the fact that I was honest...So I was truly at his mercy."

"So this guy asks me, 'What do you do professionally?' And I tell him I write movies. He says 'Is that so?' He gets up and paces up and down and then behind me, I guess he was measuring me, something like that. Comes back to his desk, picks up my passport, takes a rubber stamp and he stamps it! Then he hands it back to me, and says 'Write good ones.'"

"God bless the guy. Never knew his name, he was just an assistant or something, but I've spent the rest of my career trying to write good ones for him."

Mauvaise Graine (aka "Bad Seed")("co-directed" with Alexandre Esway, 1934) To hear star Danielle Darrieux say it, Esway was never on-set—he was an established director, and his name was used when Wilder (on the run from Nazi Germany) and some fellow ex-patriates filmed this cobbled together screenplay (the title translation is "Bad Seed") about car thieves in Paris. Rich scion Henri Pasquier (Pierre Mingand) has his "wheels" sold out from under him by his disapproving doctor-father (who had bought the car for him, anyway). What's a boy with a playboy lifestyle to do? Steal it back, of course! But, his crime is seen by three toughs in another car and after a frenetic car chase, Henri is stopped and told to follow them to a secreted garage—the hub of a car-stealing ring. At first, he's grilled to see if he's part of a rival gang, but when he explains the situation, his skill is looked upon highly enough to be asked to join. He then hooks up with fellow thieves Jean-La-Cravatte (Raymond Galle) and his sister Jeanette (Darrieux), who serves as a distraction for potential thievery victims.

For a first film, it's technically assured with some impressive chases (that, if they're under-cranked to appear faster, is only done minimally—only human running appears sped up). It's fast-paced and has some quite clever visual gags that keep the tone light even if the ethics displayed are questionable. Wilder tweaks authority figures left and right and the poor saps who get their cars stolen usually do something to deserve it. Although hard lessons are learned by the end of the film. It's rough-and-tumble, but Wilder would eventually learn to smooth things out without losing any "edge."

The Major and the Minor (1942) Wilder's first directing gig in America (after a successful script-writing career and some apprenticeship with Howard Hawks during Ball of Fire) was this screwball comedy ("a chaste version of 'Lolita'" said Wilder) where Ginger Rogers (as Susan Applegate) quits her New York job in frustration and decides to go back home to Iowa. But, she doesn't have the money to take the train as an adult, so she poses as a child named Su-su for a reduced fare. When a suspicious conductor catches her smoking, Susan takes refuge with an Army officer (Ray Milland) teaching at the military academy. Hilarity ensues. It actually does because Milland is a perfect foil for slow burns and embarrassment and Rogers is a gifted screwball comedienne. Milland's role was written for Cary Grant, but when the two were both stopped for a red light in Hollywood, Wilder called out "I'm making a picture. Wanna be in it?" "Sure!" shouted Milland. And that was it. Milland has the continental qualities of Grant, and the same comedic gifts, but has a vulnerability Grant can't be imagined with. The movie has the same hallmarks as Bringing Up Baby. Milland's officer is engaged to the wrong woman, and eventually, Susan conspires to break them up to have him for herself. So, how do you transition from a kid to an adult to convince him to fall in love with you? I mean, we're not talking Roman Polanski here. The Major and the Minor is clever, saucy, spirited and smart, It was a big hit for both Rogers and Milland, who would do another film with Wilder very soon.

Best line: "Why don't you slip out of that wet coat and into a dry martini?"

Double Indemnity (1944) Wilder tackles the post-WWII world of film noir and takes it out of B-pictures and puts it on the A-list. For writing it, he turned to an authority—Raymond Chandler and the two had a prickly relationship. You'd never know it from the script, adapted from James M. Cain's novel, which is a variation of his "The Postman Always Rings Twice"—Boy Meets Girl, Girl Convinces Boy to Murder her Husband. Boy Wises Up Too Late.

The Major and the Minor (1942) Wilder's first directing gig in America (after a successful script-writing career and some apprenticeship with Howard Hawks during Ball of Fire) was this screwball comedy ("a chaste version of 'Lolita'" said Wilder) where Ginger Rogers (as Susan Applegate) quits her New York job in frustration and decides to go back home to Iowa. But, she doesn't have the money to take the train as an adult, so she poses as a child named Su-su for a reduced fare. When a suspicious conductor catches her smoking, Susan takes refuge with an Army officer (Ray Milland) teaching at the military academy. Hilarity ensues. It actually does because Milland is a perfect foil for slow burns and embarrassment and Rogers is a gifted screwball comedienne. Milland's role was written for Cary Grant, but when the two were both stopped for a red light in Hollywood, Wilder called out "I'm making a picture. Wanna be in it?" "Sure!" shouted Milland. And that was it. Milland has the continental qualities of Grant, and the same comedic gifts, but has a vulnerability Grant can't be imagined with. The movie has the same hallmarks as Bringing Up Baby. Milland's officer is engaged to the wrong woman, and eventually, Susan conspires to break them up to have him for herself. So, how do you transition from a kid to an adult to convince him to fall in love with you? I mean, we're not talking Roman Polanski here. The Major and the Minor is clever, saucy, spirited and smart, It was a big hit for both Rogers and Milland, who would do another film with Wilder very soon.

| |||

| "There's an epidemic going around...they all think they're Veronica Lake" |

Five Graves to Cairo (1943) Wilder's second directing job was far more dramatic—based on a World War I play ("Hotel Imperial"), but transported to the currently rumbling Second World War. Franchot Tone plays John Bramble (Grant didn't want this role, either), sole survivor of his British tank unit's run-in with Erwin Rommel's Afrika Corps, who hides out in a hotel, The Empress of Britain, run by Akim Tamiroff. The Empress has taken a shelling the previous night, and, with the cook having run off during the British evacuation and the waiter being killed in the attack, they are short-staffed except for Tamiroff and the French chambermaid Mouche (Anne Baxter). So, after a brief recuperation, Bramble is pressed into service as waiter when Rommel (Erich von Stroheim) rides into town and requisitions The Empress for his headquarters to hold a special summit with his commanders. Things get complicated when Rommel demands a meeting with Bramble—the waiter he's posing as was a German spy. Perilous situation if he's found out, but he uses the opportunity to ascertain where Rommel had hidden five ammunition dumps before the war that will help the Allies if he can get the information to them in time.

Given the war-climate at the time, Five Graves to Cairo was a risky venture with news headlines threatening to make the story past its prime. But Wilder and Brackett manage to throw in topics that keep it contemporary, like the attitude of the French and Germans concentration camps, and makes a busy piece of war propaganda without waving too many flags.

The film was nominated for Oscars for Best Cinematography, Best Editing, and Best Art Direction. Having already won an Oscar for co-writing Ninotchka, Wilder the director was already receiving accolades from Hollywood.

Double Indemnity (1944) Wilder tackles the post-WWII world of film noir and takes it out of B-pictures and puts it on the A-list. For writing it, he turned to an authority—Raymond Chandler and the two had a prickly relationship. You'd never know it from the script, adapted from James M. Cain's novel, which is a variation of his "The Postman Always Rings Twice"—Boy Meets Girl, Girl Convinces Boy to Murder her Husband. Boy Wises Up Too Late.

The Boy in question is the narrator of the piece, telling the story into his Dictaphone. He's an insurance salesman named Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray*), who pays a call on the Dietrichson's (Tom Powers, Barbara Stanwyck) about taking out a life insurance policy. The Mister is interested in the policy. Neff is interested in the Mrs, Phyllis, and she seems to return the attention. Neff's smart, cynical, but in all the wrong places and she's smart enough to make him very, very dumb. If he weren't so hot and bothered, cooler heads would prevail—cooler heads like fellow agent Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), who's been at the insurance game for awhile and knows far more than he lets on. He's a mentor of sorts to Neff, but Neff is an up-and-comer, full of himself enough to think that brio and guile can make up for integrity.

McMurray had previously played tall, comfortable light romantic leads, but Wilder cast him against type, and he gives an inspired performance, evoking intelligence and oiliness, while delivering even the most forward dialogue with a clipped, joking growl. Stanwyck had been in Ball of Fire, written by Wilder, and he knew she could play a sex-pot (she had, after all, been in one of the most salacious films of the pre-Code era, Baby Face), but her Dietrichson has a cold veneer that seems to go right to the heart and right through to her soul, no matter how much heat she puts out. And Robinson gives another scholarly performance, like his detective in The Stranger, he is the moral compass, but also a slightly threatening figure. Double Indemnity is tough-as-nails and as cold-blooded a noir as they come.

Best line: Phyllis: I wonder if I know what you mean.

Walter Neff: I wonder if you wonder.**

Chandler and Wilder

The Lost Weekend (1945) Don Birnam (Ray Milland) is an aspiring writer, drunk and sober, caught in a self-defeating loop of dependence and neurosis. His dependence on, and devotion to, alcohol has put him into a tail-spin of false confidence and self-loathing where his dreams are only out of reach because he can't pick himself off the floor. His "rye" attitude drowns his dreams and feeds his nightmares and without it, he's brittle, paranoid and living in the future, waiting for the shot-glass aimed at his destruction.

Sounds like so much fun. Sounds like a "speech" or a lecture coming on. Sounds like one of those movies "for your own good." Sounds like I'd rather have a drink. Fortunately, Billy Wilder's in charge, and yes, it's preachy at times, but most of the time, it's tough as nails and doesn't hold back on what a louse Birnam is without alcohol, and how pathetic he is with it. It's not "Pity-Party: The Movie." Wilder makes it clear that Birnam is his own worst enemy and the alcoholism is just a symptom. At movie's start with Birnam barely through a week of sobriety and packing for a trip in the clean country upstate New York with his brother (Phillip Terry), it's all he can do to keep from eyeing the bottle he has hanging out his apartment window. Milland's performance is brittle, officious—like Cary Grant without the stick pulled out. But, once his brother and girlfriend (Jane Wyman, pathetically co-dependent) are out of the way, Milland's eyes go snaky looking for alcohol in his apartment's old familiar places. Then, once he's got a burn going on, Milland is in full glory as an actor—an amazing performance, eerily reminiscent of Gloria Swanson's Norma Desmond four years in the future (and also directed by Wilder).

There are joys aplenty in this film, not just from some cracker-jack writing, but also Wilder's direction—putting Milland in front of a subtly discombobulating projection-screen for his long "wild turkey" chase to find a liquor store open on a Jewish holiday, the nightmare sequence of the "alky" ward and the subsequent "screamin' meemie" sequence in his apartment. There are also great performances by Howard Da Silva as a particularly wary bartender, and a wonderfully creepy performance by Frank Faylen, who is eerily complacent telling Birnam about the tortures of DT's.

Part tract, part horror film, but without the absurd homilies or Reefer Madness hysteria, The Lost Weekend lets you off with a warning this time. The Lost Weekend was a co-winner of the Grand Prix at the very first Cannes Film Festival (Ray Milland won Best Actor), and it went on to win Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Actor. Only three films in history have won both the best prize at Cannes and the Best Picture Oscar (the others being Marty and Parasite. Premiere Magazine voted it one of it's "25 Most Dangerous Movies."

Best line: One's too many and a hundred's not enough. The Emperor Waltz (1948) Wilder was interested in making a film about post-war Europe and went there to do some scouting and research. What he saw of his former homeland so depressed him, he decided to make a musical-comedy, instead, with his home-studio's biggest star, Bing Crosby. The story, by Wilder and Brackett, is based on a true story about a Dutch inventor petitioning Emperor Franz Joseph to finance his magnetic recording device. It is 1910, and Crosby plays Virgil Smith, a traveling American gramophone salesman from Newark, New Jersey, trying to sell the Emperor in order to boost sales. But, his persistent "foot-in-the-drawbridge" aggressive sales tactics runs afoul of another schemer trying to get Franz Joseph's attention—the Countess Johanna von Stolzenberg-Stolzenberg (Joan Fontaine, who shows a flair for light comedy her dramatic roles never implied) whose family fortunes will be improved by the arranged mating of her prize poodle Scheherazade with the Emperor's dog. Trouble is Virgil's gramophone mascot Buttons keeps getting into a scrap with her and the resulting nervous breakdown of the dog—Wilder and screenwriter Charles Brackett even bring in a Viennese psychiatrist to try and cure her—may throw a bone into the whole works.

The Emperor Waltz (1948) Wilder was interested in making a film about post-war Europe and went there to do some scouting and research. What he saw of his former homeland so depressed him, he decided to make a musical-comedy, instead, with his home-studio's biggest star, Bing Crosby. The story, by Wilder and Brackett, is based on a true story about a Dutch inventor petitioning Emperor Franz Joseph to finance his magnetic recording device. It is 1910, and Crosby plays Virgil Smith, a traveling American gramophone salesman from Newark, New Jersey, trying to sell the Emperor in order to boost sales. But, his persistent "foot-in-the-drawbridge" aggressive sales tactics runs afoul of another schemer trying to get Franz Joseph's attention—the Countess Johanna von Stolzenberg-Stolzenberg (Joan Fontaine, who shows a flair for light comedy her dramatic roles never implied) whose family fortunes will be improved by the arranged mating of her prize poodle Scheherazade with the Emperor's dog. Trouble is Virgil's gramophone mascot Buttons keeps getting into a scrap with her and the resulting nervous breakdown of the dog—Wilder and screenwriter Charles Brackett even bring in a Viennese psychiatrist to try and cure her—may throw a bone into the whole works.Eventually, the Countess and the Traveling Salesman reach a fait accompli to achieve both their goals, but in Lubitschian irony, things can never run too smoothly, and don't quite turn out the way either intended, falling in love and, for the best of intentions, falling out of love again.

Reportedly, Crosby and Wilder did not get along; Crosby—with a couple "Road" movies under his belt—felt every right to change the screenwriters' words, and as a box office star for the studio, played it the way he wanted to. This also nettled Fontaine, who, despite her performance, barely spoke to the crooner between takes, as he was aloof throughout the shooting. One thing amazing about it is its cinematography (by George Barnes) and art direction are eye-popping in vivid Technicolor, for Wilder's first color film.

It's actually a rather charming and subtle satire about class and European and American contrasts in all things...everything. There's even a dig at the idea of racial purity.

Like poets say "it's perfectly swell."

Countess Johanna: What's that noise?

Virgil Smith: Oh, that? That comes from the village. Ya know, in the day-time, they make violins. In the evenings, they fiddle."

A Foreign Affair (1948) Wilder's post-war Europe film features a lot of devastating footage of a pulverized Berlin. It's a romantic comedy mixed with duplicitous motives as a congressional committee travels to Berlin to see how efficiently the taxpayer's money is being spent on the Marshall Plan. The Army wants to co-operate, of course, but the G.I. assigned to chaperone Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur), Captain John Pringle (John Lund) doesn't, lest she find out about his black-market concerns and of his consorting with one Erika von Schluetow (Marlene Dietrich, a Wilder friend), a chanteuse and the suspected mistress of a high SS officer. The tension comes from the by-the-book Frost being led astray, both professionally and—to serve that purpose—romantically by Pringle who will bend every rule to keep the status quo.

A Foreign Affair (1948) Wilder's post-war Europe film features a lot of devastating footage of a pulverized Berlin. It's a romantic comedy mixed with duplicitous motives as a congressional committee travels to Berlin to see how efficiently the taxpayer's money is being spent on the Marshall Plan. The Army wants to co-operate, of course, but the G.I. assigned to chaperone Congresswoman Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur), Captain John Pringle (John Lund) doesn't, lest she find out about his black-market concerns and of his consorting with one Erika von Schluetow (Marlene Dietrich, a Wilder friend), a chanteuse and the suspected mistress of a high SS officer. The tension comes from the by-the-book Frost being led astray, both professionally and—to serve that purpose—romantically by Pringle who will bend every rule to keep the status quo.It would have been a perfectly smart, cynical film for the likes of Cary Grant (he and Arthur had previously been paired in Howard Hawks' Only Angels Have Wings and whom Wilder continually sought, unsuccessfully, to star in one of his films). Instead, John Lund—a second-hand (slightly used) Clark Gable—plays the lead and does a fairly decent job with the sharply cynical Wilder-Brackett dialog. But, it's Dietrich and Arthur who are revelations in this, the two women on either side of a basically duplicitous snake-in-the-grass, in a tug of war to see who will get the rotten apple. Dietrich has always played the mischievously duplicitous well, but she's darkly humorous and tragic simultaneously in her role as an opportunist down on her luck and finding the next step to pull herself back out. And Arthur's quick-silver reactions still come to the fore even though she's playing a stereotypical Hollywood stick-in-the-mud—she even pulls off the most unbelievable character transitions and still has you rooting for her. It's a richly cynical film (over footage of the bombed out Berlin, Wilder has the audacity to accompany it with the ballad "Isn't It Romantic?"), but Wilder was only getting started with that approach, as his next films would attest.

Best line: Underneath (that building) is a concrete basement. That's where (Hitler) married Eva Braun and that's where they killed themselves. A lot of people say it was the perfect honeymoon.

Sunset Boulevard (1950) Billy Wilder's poison-pen letter to Hollywood and its excesses might be Wilder's greatest film. It certainly has inspired casting going for it. It is probably the most vituperative, back-stabbing, self-hating, malicious and just-plain-cynical look at the glamour of Hollywood. It is also a brilliant film with a capital "B". Joe Gillis, is a down-on-his-luck writer who, when, being chased by his creditors, happens upon the estate of Norma Desmond, a once-great silent film queen.

Now, consider the casting: Norma Desmond, "once-great silent film star" is played (and played brilliantly) by Gloria Swanson, "once-great silent film star." Her servant, Max von Mayerling, once-great-director-destroyed-by-Hollywood's-system, is played by Erich von Stroheim, once-great director-destroyed-by-Hollywood's-system. Hack writer Joe Gillis is played by William Holden who, more than any other actor is director-writer Billy Wilder's cinematic alter-ego. It is cruel in how it treats the old discarded Hollywood, and it is cruel (and probably right) in the view of the 1950's Hollywood being just as bad with its over-eager starlets and corrals of hacks like Gillis. It is filled with a black steaminess—a fetid atmosphere. It shows a view of Hollywood as something like a Venus Fly-trap, something that looks lovely and inviting from a distance, but once you get up-close you find that is merely a plot to attract and drag you in.

Another thing: this movie is full, dense with ideas and brilliant strokes by its creators with reverberations that go beyond the film. When you leave the theater it haunts you even more effectively than a finely crafted horror film. It IS a horror movie—with a black widow spider at the hub of a web, dragging everything around her touch into degradation and death. Maybe I should say that, in the first of bizarre touches that create the film's atmosphere, that Joe Gillis narrates the film, even as we see him floating face-down dead in Norma Desmond's swimming pool.

Quite a few other films (and one highly-rated television series) have used that "speaking from the grave" bit since. It's the ultimate authority for putting things in perspective. But that was Wilder being conservative. He initially wanted Gillis to sit up in the police morgue and start telling the story from his slab.

I think you can make a case for Sunset Boulevard being prime film-noir (and maybe an American Grand Guignol), as Wilder was adept at it. The only thing leavens the bite a bit is the dark humor of it all, inspired by the excess and fatuousness of the movie-making scene. It's not so amazing that Hollywood let Wilder do this film. Every few years some disgusted writer or director claims to make an expose that'll blow the lid off Hollywood, be it A Star Is Born, or The Big Picture, or S.O.B., or An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn.

Yeah, yeah. They all pale in comparison to Sunset Boulevard which, with its first frame, starts in the gutter and stays there until its last shimmering-with-Vaseline fade to pitch-black. It doesn't surprise me at all that Gloria Swanson returned to movies for this part. It's a fearless performance, full of self-awareness and assured brio. It would stay with her the rest of her life, and she would play a benign version of the role in what little work she did later on. It is interesting that Erich von Stroheim agreed to his butler role as he was a silent film director (and star) whose career was stalled by the extravagant budgets on his films—in fact, the "Norma Desmond" film that she shows Gillis was directed by von Stroheim (the barely-released Queen Kelly). It's also curious that Cecil B. DeMille participated in it, but not really. Although extremely conservative, it gave DeMille an opportunity to trumpet his new version of Samson and Delilah, (and get paid doing it). That's the movie he's shown filming in his scenes.

And the movie's DID get small.

Sunset Boulevard is one of those must-see films. Just have a shower ready for after.

Best line: We had faces then!

Ace in the Hole (aka The Big Carnival)(1951) One of my favorite films (probably because it was such a box-office bomb), Ace in the Hole tells the story of an ambitious reporter playing in the minor leagues of a small town, who takes the story of a minor cave-in disaster and turns it into a story of national import. In my little piece on Ace, I tried to explain why it didn't generate an audience when the previous year's Billy Wilder film Sunset Boulevard did: The screenplay, by Wilder, Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman, has its ink mixed with venom, but it's no worse than the cynicism expressed in Wilder's previous film, Sunset Boulevard. The difference is Wilder's not looking at the easily-satirized egotism of Hollywood, he's looking at us, and the American capacity to make a buck while wallowing in tragedy. Ace in the Hole is before its time, before the mawkishness and the trivial pursuit of the 24 hour news cycle made the trend easier to spot.

And there's one other thing: Sunset Boulevard's dispassionate cynic was William Holden, "the golden boy," whose snide wise-cracks passed for intelligence. Here, he's Kirk Douglas, who is a more energetic performer, and so that constant cynicism is seen as more of a constant attack that just seems mean-spirited. And where Holden's self-loathing seemed somehow relaxed and noble, Douglas's is never less than actively self-destructive. It's a smarter, more satisfying performance that doesn't try to be likable, or a wolf in sheep's clothing, but audiences found it repellent (as well they should!). They didn't want their movie-heroes (or anti-heroes) to be too unlikable. So, even though there is no redemption for this character, and no happy ending in sight, the crowds stayed home from Ace in the Hole, even after Paramount re-released it with the deceptively sunnier title of The Big Carnival.

That doesn't stop it from being the classic that it is, of Billy Wilder (who famously said "They say that you're only as good as your last picture. You're only as good as your best picture") in his prime.

Best line: Lorraine: I don't go to church. Kneeling bags my nylons.***

Stalag 17 (1953) Writers Donald Bevan and

Edmund Trzcinski were POW's at the Nazi's Stalag 17B in Austria. They collaborated on a play about their experiences in "Stalag 17" which opened in May of 1951, and despite its subject matter, was a huge hit on Broadway. When it completed its run, it was picked up for the movies and Wilder—this time collaborating with scriptwriter Edwin Blum—brought along some of the cast for the movie. But, not the two leads. For the Camp Commandant, Wilder hired autocratic German director Otto Preminger—a witty touch. But, the lead was problematic. Wilder and Blum decided to make much of the sentiment out of the play making the lead character of Sefton more selfish and less heroic and offered it to Charlton Heston, who refused, hating the changes. So did second choice Kirk Douglas. So did third-choice William Holden. But, Holden had worked with Wilder before and Paramount insisted he take the role, so he took a chance, all the time complaining that his character was unlikable. Wilder stood firm. Holden ended up winning the Oscar for Best Performance by an Actor that year.

Edmund Trzcinski were POW's at the Nazi's Stalag 17B in Austria. They collaborated on a play about their experiences in "Stalag 17" which opened in May of 1951, and despite its subject matter, was a huge hit on Broadway. When it completed its run, it was picked up for the movies and Wilder—this time collaborating with scriptwriter Edwin Blum—brought along some of the cast for the movie. But, not the two leads. For the Camp Commandant, Wilder hired autocratic German director Otto Preminger—a witty touch. But, the lead was problematic. Wilder and Blum decided to make much of the sentiment out of the play making the lead character of Sefton more selfish and less heroic and offered it to Charlton Heston, who refused, hating the changes. So did second choice Kirk Douglas. So did third-choice William Holden. But, Holden had worked with Wilder before and Paramount insisted he take the role, so he took a chance, all the time complaining that his character was unlikable. Wilder stood firm. Holden ended up winning the Oscar for Best Performance by an Actor that year.It's interesting that, after directing a box-office flop for Paramount, Wilder chose to make Stalag 17 grittier and less sentimental than its source, not pandering to audiences, but challenging them. Not to say there aren't a load of laughs in Stalag 17. There are. But, his insistence on making Holden's Sefton a jerk and having his stalag-mates attack him viciously for suspected collaboration (as well as his opportunism) does not paint Americans in an audience-friendly light. His integrity paid off, however. Stalag 17 was a big hit for Paramount. But, Wilder's pay-out was reduced as the studio took the Ace in the Hole losses out of his paycheck.

Wilder would not renew his contract with Paramount thereafter.

Best line: Oberst Von Scherbach: I'm grateful for a little company. I suffer from insomnia.

Lt. James Skylar Dunbar: Did you ever try 40 sleeping pills?

Best line: Oberst Von Scherbach: I'm grateful for a little company. I suffer from insomnia.

Lt. James Skylar Dunbar: Did you ever try 40 sleeping pills?

Sabrina (1954) Samuel Taylor's "Cinderella" story, "Sabrina Fair: A Woman of the World," had been a hit on Broadway and, following its run, Paramount picked it up for Wilder's last film on his contract (before moving on to Warner Brothers). As usual, Wilder wanted changes to the play, so Taylor walked and Ernest Lehman came in. For the chauffeur's daughter who goes off to Paris to return as a sophisticated woman of the world Paramount cast its new sensation (and contract player) Audrey Hepburn, who'd followed up a starring role in Broadway's "Gigi" with an Oscar-winning performance in Paramount's Roman Holiday. Again, Wilder sought out Cary Grant to play the older of the two smitten Larrabee brothers, but Grant refused (as he had done with ...Holiday) saying that he was too old to play opposite such a young ingenue of 24 (although he did co-star with her in Charade nine years later in one of his last roles).

Sabrina (1954) Samuel Taylor's "Cinderella" story, "Sabrina Fair: A Woman of the World," had been a hit on Broadway and, following its run, Paramount picked it up for Wilder's last film on his contract (before moving on to Warner Brothers). As usual, Wilder wanted changes to the play, so Taylor walked and Ernest Lehman came in. For the chauffeur's daughter who goes off to Paris to return as a sophisticated woman of the world Paramount cast its new sensation (and contract player) Audrey Hepburn, who'd followed up a starring role in Broadway's "Gigi" with an Oscar-winning performance in Paramount's Roman Holiday. Again, Wilder sought out Cary Grant to play the older of the two smitten Larrabee brothers, but Grant refused (as he had done with ...Holiday) saying that he was too old to play opposite such a young ingenue of 24 (although he did co-star with her in Charade nine years later in one of his last roles).Instead, the studio cast Humphrey Bogart (at 54, four years older than Grant) as the older, more sensible head of the Larrabee Corporation, and 35 year old William Holden as the younger, less responsible second-in-line. Bogart liked the money, but thought he was too old for the part, thought Hepburn too young and inexperienced (he would have preferred wife Lauren Bacall) and irritated with Holden, and was, generally, miserable on the set (he later apologized to Wilder). But, even though he's excellent in the part as written, he was simply too old for the part, especially alongside Hepburn.

One interesting aspect to it: Wilder managed to sneak in a couple references to the play "The Seven Year Itch" which would be his next project...for the rival Warner Brothers studio!

Sabrina would be remade in 1995 by Sydney Pollack with an eye towards lessening the age disparity, but, again, it seemed a bit "off."

Best Line: The 20th century? I could pick a century out of a hat, blindfolded, and get a better one.

The Seven Year Itch (1955) Although it is most famous for it, the film has so much more to offer than the shot of Marilyn Monroe's skirt blowing up over a subway grill...much more. It's just tough to get past that image...all five seconds of it. In fact, the film might be my favorite Billy Wilder film...if it weren't for Sunset Blvd., Ace in the Hole, The Apartment, Double Indemnity, Lost Weekend,Some Like It Hot, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (and on and on). As it is, it's unique among Wilder films (which seem all to be unique) in that it is basically a one-man show, a monologue (which makes Monroe's dominance of it so mysterious...but only proves her power) by Tom Ewell, the bassett-hounded everyman-actor, who played the role on Broadway (900 times over three years). Ewell wasn't a comedian, he was a serious actor, and his playing of this sexed-up version of Thurber's "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty," never betrays a need to evoke laughs. No, he plays it straight, even tragically, and garners belly-laughs. Even his vast experience with the role contributes to the world-weary quality of his fantasy sequences and the beleaguered "I'm too sexy for this life..." attitude that permeates the performance.

Best Line: The 20th century? I could pick a century out of a hat, blindfolded, and get a better one.

The Seven Year Itch (1955) Although it is most famous for it, the film has so much more to offer than the shot of Marilyn Monroe's skirt blowing up over a subway grill...much more. It's just tough to get past that image...all five seconds of it. In fact, the film might be my favorite Billy Wilder film...if it weren't for Sunset Blvd., Ace in the Hole, The Apartment, Double Indemnity, Lost Weekend,Some Like It Hot, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (and on and on). As it is, it's unique among Wilder films (which seem all to be unique) in that it is basically a one-man show, a monologue (which makes Monroe's dominance of it so mysterious...but only proves her power) by Tom Ewell, the bassett-hounded everyman-actor, who played the role on Broadway (900 times over three years). Ewell wasn't a comedian, he was a serious actor, and his playing of this sexed-up version of Thurber's "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty," never betrays a need to evoke laughs. No, he plays it straight, even tragically, and garners belly-laughs. Even his vast experience with the role contributes to the world-weary quality of his fantasy sequences and the beleaguered "I'm too sexy for this life..." attitude that permeates the performance.

Richard Sherman (Ewell) works for a paperback company that specializes in marketing dull titles with salacious covers. At the start of a long, hot summer, he sends his wife (Evelyn Keyes) and son (Tom Nolan) to her family in Maine to get them out of the sweltering city of New York. The vacation offers pastoral pleasures like kayaking, but Sherman is left to sin upstream with the paddle. He is the perfect domesticated husband, but his "overactive imagination," making him so good at marketing, is a constant battlefield. However good he might be, giving up smoking ("all those lovely, injurious tars and resins," he sighs), not drinking, eating at health-food restaurants, he still has "urges" to misbehave.

Emphasis on the "Miss," an unnamed upstairs neighbor (Marilyn), model, and frequent guest of her upstairs neighbors, "the interior decorators or something." "Being good" does not come easy when Sherman has to figure out how to "sell" his company's latest manuscript—a psychological text on the sexual urges of repressed middle-aged males (which to Sherman reads like an auto-erotic-biography). An office visit from the doctor only confirms what everybody, real or fantasy, has already told him—he's got an overactive imagination (code for libido, and it "breaks out" in nervous tics, itching, scratching and neurosis) and no perspective about his appeal (or lack of it) as a man, seeing every woman in his orbit as an attractive force, and he—brave soul—is a stalwart unmovable object, despite "the girl" hanging over his head from her balcony.

Ewell is amazing, but everybody's good and all the actors are clicking along on all cylinders, with crack comic timing. Monroe is great, too. This isn't one of her later "one-note" performances. Her "girl" is a comic innocent, and Monroe's versatile enough to personify all of Sherman's fantasy versions of her.

The play is different. It's not so chaste, and, reportedly, Wilder and Axelrod were frustrated with the restrictions imposed by the Hayes Office. But what is there is great, with very little slack in pacing, and Ewell's amazing work throughout. He deserves so much of the credit for making the film as consistently entertaining as it is. But, as in the film, he's helpless to conquer Monroe's image.

Sadly, neither was she.

Best line: Miss Morris, I'm perfectly capable of fixing my own breakfast. As a matter of fact, I had a peanut butter sandwich and two whiskey sours.The Spirit of Saint Louis (1957) When Charles Lindbergh published his autobiography "The Spirit of St. Louis" in 1953, it was immediately snapped up by Warner Bros. to become a major motion picture, but they had no idea how tough and daunting it would be. One of its biggest advocates was James Stewart, who lobbied hard for the role of the 25 year old Lindbergh (despite being 47 at the time of filming) over the objections of studio head Jack Warner. Wilder tamps down his satirical instincts for a straight-ahead presentation of the demands and difficulties that Lindbergh's transatlantic flight presented the young aviator. But, he didn't anticipate the difficulties in making the picture. Three versions of the $10,000 "Spirit" were re-created at a cost of 1.3 million dollars and cost overruns plagued the production (due to the finicky nature of weather and technical issues) to double its original 3 million dollar budget and the shooting schedule from 64 days to 115—enough to have to work around Stewart's filming of two subsequent movies.

It didn't make money, even prompting Jack Warner to gripe it was "the most disastrous failure we've ever had."

Love in the Afternoon (1957) This one had me smiling immediately with Maurice Chevalier's opening narration—"Zis is the city, Paris France"—echoing Jack Webb's "Dragnet" opening. Chevalier plays a private detective, Claude Chavasse, specializing in "matrimonial work," and lately the case-work has been dominated by one subject, American millionaire Frank Flannagan (Gary Cooper), who is cutting a wide swath through the world's female population, both married and unmarried divisions. The work has turned Chavasse into a cynic about the paths of love—he's gumshoed too many of them—in marked contrast to his daughter, Ariane (Hepburn), a cello player (hold that image in your head for a moment), still wide-eyed at the prospect of romance, and fascinated with her father's work, something he does his utmost to discourage.

When she gets wind that a cuckolded husband (John McGiver, hyperventilating amusingly in fine comic fashion) plans on breaking in on his wife's tryst to ventilate Flannagan, she steps in from the balcony to insert herself into the situation. This leads inevitably (in the movies, at least) to an affair between the elder lothario and the young ingenue, one that she manipulates by trying to talk a competitive game in conquests. The situation is ripe with comic possibilities, which Wilder exploits every chance he gets, even using Flannagan's moving musical accompaniment (his final assault is preceded by a four piece rendition of "Fascination").

Much has been made of Cooper's age in the film, and it is an issue. Cary Grant was supposed to be Flannagan (Wilder had been trying to entice Grant into one of his films for years) but when a deal wasn't reached, Cooper, who, at 56 was Grant's senior by three years, was hired. Cooper is an odd fit, as opposed to younger men like, say, Gregory Peck (as in Roman Holiday) or William Holden (in Sabrina), but Wilder works around it, initially, keeping Coop' in shadow to emphasize his "mystery man" status, and Cooper's early performance is, interestingly, boyish and somewhat immature.

And that's the point. Flannagan is a man-child, used to getting everything he wants. And Ariane has her choice between younger men—immature and unsophisticated—and Flannagan—sophisticated but immature. All it takes for him to grow up is a level of commitment, something he's avoided his whole life by having a train to catch. Both character arcs feel complete and satisfying, even though it is the "7-10 split" of May-December romances, and one feels a little creepy watching them make out.

And a little guilty, in the same way that it was tough to watch the denouement of Sabrina. Okay, it's charming that she likes the old guy, but if he really was thinking this through, with all this new-found maturity, wouldn't he be thinking about her, and what she has to look forward to in a life with him (which can be summed up in one word..."short")?

And then, one considers Wilder, and the blithe, darkly cavalier sensibility that he brought to the movies, moral though his stand-point might be. One can imagine Wilder, the guy who ended Some Like It Hot with "Nobody's perfect," with a similar tag for this movie: "Aren't you concerned about the age difference?" "If she dies, she dies..."

Initially condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, it was marked "safe" after Wilder changed the ending with a Chevalier narration in the same "Dragnet" style: "On Monday, August 24th of this year, the case of Frank Flannagan and Ariane Chavasse came up before the superior judge in Cannes. They are now married, serving a life sentence in New York, state of New York, USA."

Best line: This is the city. Paris, France.

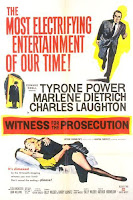

Witness for the Prosecution (1957) Agatha Christie's long-running play is adapted by Wilder and Harry Kurnitz (with an adaptation credit by Lawrence B. Marcus) concentrating less on the trial than the characterization of defense barrister Sir Wilfred Roberts (Charles Laughton, who relished the role), a wily lawyer just returning to work after suffering a heart attack—Kurnitz and Wilder also added the hysterical interplay between Roberts and his nagging nurse (played by Elsa Lanchester, Laughton's wife). Sir Wilfred's first day has an intriguing dilemma—although doctor's orders are for him to stay away from murder cases: Solicitor Mayhew (Henry Daniell) implores Roberts to take the case of one Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power) accused of murdering Mrs. Emily Jane French, a "friend" of his who had recently (and conveniently) changed her will to include him. Vole is a bit of a charming cad, and something of a ne'er-do-well, but capable of murder? His German wife Christine Helm-Vole (Marlene Dietrich) also has an iron-clad alibi for her husband, which Sir Wilfred tells her he can't use—no jury would believe that she wouldn't lie to save her husband. So, imagine his surprise when Christine is called to offer testimony...for the prosecution, saying that Leonard did, indeed, commit the murder, condemning the man to an almost certain guilty verdict and the death penalty.

Of course, the trial doesn't end there, with some notable Christie psychological trickery—and a twist that audiences were warned not to reveal at the end of the picture (even the Royal Family had to sign a vow not to mention it) and almost certainly cost one of the stars an Oscar nomination. Wilder already had strong material to work with and the actors all threw themselves into their roles (both Laughton and Dietrich developed crushes on Tyrone Power, who died of a heart attack shortly after the film was made), and although it's not typical Wilder, it shows a strong directorial hand that only enhances the story.

Bestline: Miss Plimsoll: It's beddy-bye! We better go upstairs now, get undressed, and lie down.

Sir Wilfred: We? What a nauseating prospect.

Some Like it Hot (1959) Wilder's first collaboration with I.A.L. Diamond, who would, subsequently co-write all of the director's films. It started—as a few of Wilder's films do—with an earlier foreign work, in this case an obscure 1935 French farce called Fanfare of Love. Wilder and Diamond's adaptation had two musicians Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon, his first film for Wilder but definitely not his last) as two barely scraping-by musicians working at a speak-easy who have the bad luck to witness the St. Valentine's Day Massacre (presided over by George Raft) and to escape the mob, take jobs as players for an all-girl band, "Sweet Sue and Her Society Syncopaters".

The make-up demands to turn Curtis and Lemmon into women forced the movie to be made in black-and-white—although to test it, Wilder demanded that the two try to "pass" in a women's bathroom and when they emerged undetected, the director declared the job done.

The band's ukelele player and singer Sugar "Kane" Kowalczyk was written for Mitzi Gaynor, but Marilyn Monroe wanted the part and she got it, even ignoring her contract demand for the film to be in color when she saw the make-up tests on Curtis and Lemmon. It had been some time since Monroe's last film, The Prince and the Showgirl—where she'd had difficulties with director Laurence Olivier—and her perfectionism, insecurities, and troubled personal life caused issues on the set. She was perpetually late and Curtis and Lemmon secretly made bets on how many tries it would take for her simplest lines. Yet (as Olivier found out) even a scattered Monroe still had that indefinable "something" no one could direct. And then, there were days—the beach scene between Monroe and Curtis—posing as a "Shell Oil family member" and doing a wicked imitation of his idol, the always unavailable Cary Grant—completed filming in only 20 minutes (for what was scheduled for three days).

They say that a successful picture has to have some miracle factor to it, and the risky, funny Some Like It Hot was a disaster waiting to happen that turned into a miracle. Rude, silly, hilarious, and, despite that, no lessening of the stakes involved, the ungainly duckling soars like a swan, while also mischievously tweaking the boundaries imposed by "The Hays Code" leaving "the industry rules" looking old-fashioned and out-of-touch.

Some Like it Hot was one of the few films ever voted "Condemned" by The Catholic Legion of Decency.

But no Legion of Decency is perfect.

Best line: Story of my life. I always get the fuzzy end of the lollipop.****

The Apartment (1959) Inspired by a scene from David Lean's film of Brief Encounter, The Apartment tells the story of C.C. "Bud" Baxter (Lemmon), working for a major insurance company as one of the many drones stranded behind desk and adding machine—the mammoth working pool set, a miracle of forced perspective looks like it covers several city blocks and feels like you should pack a lunch just to cross it. Crossing it is uppermost in Baxter's calculating skull. And to that end, he uses everything at his disposal, including lending his apartment as a love-nest for the married executives to pursue...outside interests. That apartment should have a revolving door on it, as Baxter must keep a scheduler as well as a well-stocked liquor cabinet. The arrangement helps him get ahead and the personal recommendations brings him to the peaked attention of the company's personnel director Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray) who has need of the Apartment himself.

Baxter is climbing the ladder now, but it's one of the elevator operators, Miss Francine Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine) that gets a rise out of him. They start a flirty relationship that Kubelik is a little cool to pursue, seeing as she is on a downward spiral in a relationship with Sheldrake. For Baxter, it will become a case of clashing ambitions.

The situation drips with irony: an insurance company, where the exec's juggle statistics and mistresses with no moral compasses. And the hierarchy of executive structure is paralleled to the status of folks in their private lives: the mistresses are treated with contempt if they begin to interfere with the home turf. And Baxter is literally left out in the cold every night, as the executives hedonistically burn through relationships that Baxter doesn't have the roots to start. It's only when a crisis occurs that Baxter begins to grow a conscience over the moral compromises he's making and providing.

The crisis sparks something Baxter's superiors (in everything but morals) never slow down enough to experience—a caring relationship, centered around (ironically) Kubelik in Baxter's bed. Schedules get shuffled, promises broken, and complications loom that the usually organized Baxter can barely manage all in an effort to create a recuperating stillness in a hectic personal life that comes crashing into his business-life. Conscientiousness ensues.

It seems like a fairy-tale today with current rubber-board rooms of the business-world filled with sociopaths. But, at the tale end of the 50's and the concerns of the world moving away from our boys in khaki to the boys in grey-flannel, it was a cautionary tale. Revolutions of all sorts in the '60's and plagues, both sexual and financial, in the 70's have made the film seem...one shudders at the word... "quaint."

But, that doesn't affect its wit, its insight, its charm, or high entertainment quotient. As a film it's a perfectly built comedic construction, a bon-bon exquisitely made and wrapped, with just a hint of sour bitterness at its core. And in the running gag that permeates the conversation of the film, it delivers its bellyful of laughs with no disconnect to the head, on its way to the heart, intellectually-wise.

Best line: I said I had no family, I didn't say I had an empty apartment.

Some Like it Hot was one of the few films ever voted "Condemned" by The Catholic Legion of Decency.

But no Legion of Decency is perfect.

Best line: Story of my life. I always get the fuzzy end of the lollipop.****

Baxter is climbing the ladder now, but it's one of the elevator operators, Miss Francine Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine) that gets a rise out of him. They start a flirty relationship that Kubelik is a little cool to pursue, seeing as she is on a downward spiral in a relationship with Sheldrake. For Baxter, it will become a case of clashing ambitions.

The situation drips with irony: an insurance company, where the exec's juggle statistics and mistresses with no moral compasses. And the hierarchy of executive structure is paralleled to the status of folks in their private lives: the mistresses are treated with contempt if they begin to interfere with the home turf. And Baxter is literally left out in the cold every night, as the executives hedonistically burn through relationships that Baxter doesn't have the roots to start. It's only when a crisis occurs that Baxter begins to grow a conscience over the moral compromises he's making and providing.

The crisis sparks something Baxter's superiors (in everything but morals) never slow down enough to experience—a caring relationship, centered around (ironically) Kubelik in Baxter's bed. Schedules get shuffled, promises broken, and complications loom that the usually organized Baxter can barely manage all in an effort to create a recuperating stillness in a hectic personal life that comes crashing into his business-life. Conscientiousness ensues.

It seems like a fairy-tale today with current rubber-board rooms of the business-world filled with sociopaths. But, at the tale end of the 50's and the concerns of the world moving away from our boys in khaki to the boys in grey-flannel, it was a cautionary tale. Revolutions of all sorts in the '60's and plagues, both sexual and financial, in the 70's have made the film seem...one shudders at the word... "quaint."

But, that doesn't affect its wit, its insight, its charm, or high entertainment quotient. As a film it's a perfectly built comedic construction, a bon-bon exquisitely made and wrapped, with just a hint of sour bitterness at its core. And in the running gag that permeates the conversation of the film, it delivers its bellyful of laughs with no disconnect to the head, on its way to the heart, intellectually-wise.

One, Two, Three (1961) Coming off his Best Picture win for The Apartment, Billy Wilder could have played it safe. But, with the world heating up from a "Cold War" and America's response being "Coca-Cola colonialism" Wilder had to take a pot-shot in one of the most contentious places in the world. His home town of Berlin.

Coca-Cola executive for West Berlin C. R. MacNamara (James Cagney) dreams of a promotion heading London's office, which is why agrees to chaperone his Atlanta boss' daughter (Pamela Tiffin) while she's traveling in West Germany before her father's own visit to the plant. MacNamara is hoping to crack the Russian market for Coke, and so he spends less time managing the boss' daughter than he should. Just before his boss' pending arrival, daughter Scarlett shows up announcing that she has gotten married...and her husband is a communist from East Berlin, Otto Piffl (Horst Buchholz)—they met while blowing up "Yankee Go Home" balloons (which she defends because EVERYBODY in Atlanta hates Yankees). The happy couple wants to move to Moscow.

MacNamara solves the potential fracas by framing Otto for being a spy and gets him picked up by the East German police...only to find that Scarlett is pregnant. MacNamara has twelve hours to get Otto back and try to sell him as a worthy son-in-law to a Southern capitalist. The situation sounds frenetic.

As is the film. Wilder knew he was making a complicated farce and was determined to make it "the fastest picture in the world," a screwball comedy in a politically screwball world. In that, he had an ally in Cagney, who, even at the age of 60, had some of the fastest movie reflexes acting. Cagney is relentless, barking orders and doing "fast" burns while trying to manage Wilder and Diamonds' intricate dialogue (which, as Wilder always insisted, had to be done precisely as written). Even to a fan of Cagney's, knowing how quick and forceful he can be, the film feels like a hurricane fueled by his energy. Some of the inherent frustration apparent on Cagney's face was due to the over-playing of Buchholz, whom he detested. Cagney pushed himself to the point where, after filming wrapped, he retired from acting...until the minor roles he did before his death.

As relentlessly pushy as the film is, it was not a box-office success. One, Two, Three was the last Hollywood movie filmed in Berlin before the Berlin Wall was erected, making the film less of a laughing matter. Even with its relentless pace on-screen, its timing was a bit off.

Best line: Atlanta? You can't be serious! That's Siberia with mint juleps!

Irma la Douce (1963) "Irma la Douce" was a French musical which translated to being hits in the West End and Broadway, and Wilder bought the rights as a vehicle for Jack Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe. Monroe died, so Wilder re-teamed Lemmon with Shirley Maclaine, who bubbles and blows smoke in the role (and won an Oscar nomination) of a French street-walker, Irma, who, with a regular body of fellow workers, stake out a tourist section of Paris. Lemmon plays Nestor Patou, a by-the-book "flic" who is shocked (shocked!) that there are prostitutes working in Paris...in broad daylight. He arrests them, not comprehending that the pimps regularly split proceeds with the police fund, and is promptly fired by his superior Insp. Levre (Herschel Bernardi) for bribery.

Destitute and without any practical skills—and not loved by the pimp-and-hooker crowd at the nearby Chez Moustache (run by Lou Jacobi...but that's another story), Patou finds himself in a fight with Irma's pimp, manages to win, and is given room and board (with benefits) by Irma, who recruits him as her new procurer. But, he can't even do that job well; Patou falls in love with Irma and is jealous of any customers other than himself. With Moustache's help, he concocts a rich "regular" for Irma, Lord "X"...who only wishes to play double solitaire. Meanwhile, he works early mornings at the outdoor Market, so he can support Irma in the way in which she's accustomed.

It's an odd, sweet story of what a man will do for a woman, even if she's not exclusively his, with complications—at one point Nestor is arrested and convicted for the murder of Lord "X"—and Wilder again pushing the envelope of social mores and seeing what froths. The thesis of the film being: "Shows you the kind of world we live in. Love is illegal - but not hate. That you can do anywhere, anytime, to anybody. But if you want a little warmth, a little tenderness, a shoulder to cry on, a smile to cuddle up with, you have to hide in dark corners, like a criminal. Pfui."

Best line: Irma: Why are you so good to me?

Nestor: I just believe in fair dealings between labor and management.

Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) Here's a controversial one—the generally condemned Kiss Me, Stupid is probably more realistic than the fantasy of The Seven Year Itch and probably truer to real life in the obviousness of its gags, which run a little on the adolescent side. Based on an Italian play, Wilder and Diamond focus on life in a desert town (Climax, Nevada) where a Vegas entertainer Dino (Dean Martin, sending himself up) is stranded with car trouble. Two would-be songwriters Osgood and Barney (Ray Walston and Cliff Osmond) do everything they can to delay, delay, and delay to keep Dino in town until they get a chance to show him their new song, which they are sure he can turn into a big hit.

Best line: Atlanta? You can't be serious! That's Siberia with mint juleps!

Irma la Douce (1963) "Irma la Douce" was a French musical which translated to being hits in the West End and Broadway, and Wilder bought the rights as a vehicle for Jack Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe. Monroe died, so Wilder re-teamed Lemmon with Shirley Maclaine, who bubbles and blows smoke in the role (and won an Oscar nomination) of a French street-walker, Irma, who, with a regular body of fellow workers, stake out a tourist section of Paris. Lemmon plays Nestor Patou, a by-the-book "flic" who is shocked (shocked!) that there are prostitutes working in Paris...in broad daylight. He arrests them, not comprehending that the pimps regularly split proceeds with the police fund, and is promptly fired by his superior Insp. Levre (Herschel Bernardi) for bribery.

Destitute and without any practical skills—and not loved by the pimp-and-hooker crowd at the nearby Chez Moustache (run by Lou Jacobi...but that's another story), Patou finds himself in a fight with Irma's pimp, manages to win, and is given room and board (with benefits) by Irma, who recruits him as her new procurer. But, he can't even do that job well; Patou falls in love with Irma and is jealous of any customers other than himself. With Moustache's help, he concocts a rich "regular" for Irma, Lord "X"...who only wishes to play double solitaire. Meanwhile, he works early mornings at the outdoor Market, so he can support Irma in the way in which she's accustomed.

It's an odd, sweet story of what a man will do for a woman, even if she's not exclusively his, with complications—at one point Nestor is arrested and convicted for the murder of Lord "X"—and Wilder again pushing the envelope of social mores and seeing what froths. The thesis of the film being: "Shows you the kind of world we live in. Love is illegal - but not hate. That you can do anywhere, anytime, to anybody. But if you want a little warmth, a little tenderness, a shoulder to cry on, a smile to cuddle up with, you have to hide in dark corners, like a criminal. Pfui."

Best line: Irma: Why are you so good to me?

Nestor: I just believe in fair dealings between labor and management.

Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) Here's a controversial one—the generally condemned Kiss Me, Stupid is probably more realistic than the fantasy of The Seven Year Itch and probably truer to real life in the obviousness of its gags, which run a little on the adolescent side. Based on an Italian play, Wilder and Diamond focus on life in a desert town (Climax, Nevada) where a Vegas entertainer Dino (Dean Martin, sending himself up) is stranded with car trouble. Two would-be songwriters Osgood and Barney (Ray Walston and Cliff Osmond) do everything they can to delay, delay, and delay to keep Dino in town until they get a chance to show him their new song, which they are sure he can turn into a big hit.

As inducement, Osgood invites the star to his house for the evening, but, knowing his wife (Felicia Farr) is a big fan of his, he arranges a fight with her and exchanges Polly (Kim Novak), a local prostitute to take her place. Hilarity ensues, but not to anyone's comfort level.

This film is the one that broke the Billy Wilder honeymoon with Hollywood studios and the movie-going audiences. He'd been skirting the same moral delicacies in the movie moral landscapes as Otto Preminger, Alfred Hitchcock, and Elia Kazan, but had been doing it in the wittiest way possible. Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, One, Two, Three, Irma La Douce (even without music) were embraced by American audiences.

Kiss Me, Stupid was not.

Maybe it was too much a second cousin to Wilder's original vision of an adaptation of the Italian farce "L'Ora della Fantasia" by Anna Bonacci, with Jack Lemmon (busy), Marilyn Monroe (dead) and Dean Martin. Peter Sellers was cast for the Lemmon role, Kim Novak for Monroe, and filming was going along swimmingly until Sellers, newly married to Britt Ekland, suffered several heart attacks by inhaling amyl nitrate, and was replaced after the fact with Ray Walston, a fine comic actor but who lacked a schlemielish quality that might make audiences identify with him.

It's a clever idea: Armbruster is such a stifled, constipated American that he can't think of any way but his way in which to do things. And he's in Italy...heck, he's in Europe...which operates on a different clock, and respects things that Americans dismiss nowadays. Like Sundays. And people.

What a "backwards" place.

Before long, you hate everything American, and want to take an extended vacation...anywhere but here. And there's only so much one can take. For gung-ho Americans, it's an extended dig at the Motherland, and for self-loathing liberals, it's preaching to the choir. Either way, it's not an awful lot of fun to watch.

There has always been this quality to the later Wilder films—even The Apartment has it to an extent—a superior attitude that hammers points home far beyond the level of the wood, a decidedly cruel streak given to the characters not yet clued in to their own cluelessness. No empathy. No affection for the character. A decided lack of charm imprinted on the character (and this from Taylor and Wilder?*) And if I can carry the carpentry metaphor a little further, it makes what could have been an elegant finish look pretty banged up.

Kiss Me, Stupid was not.

Maybe it was too much a second cousin to Wilder's original vision of an adaptation of the Italian farce "L'Ora della Fantasia" by Anna Bonacci, with Jack Lemmon (busy), Marilyn Monroe (dead) and Dean Martin. Peter Sellers was cast for the Lemmon role, Kim Novak for Monroe, and filming was going along swimmingly until Sellers, newly married to Britt Ekland, suffered several heart attacks by inhaling amyl nitrate, and was replaced after the fact with Ray Walston, a fine comic actor but who lacked a schlemielish quality that might make audiences identify with him.

Best line: Is this a bit of terrific? Heh? Last night she was banging on my door for 45 minutes! But I wouldn't let her out.

The Fortune Cookie (1966) Billy Wilder must have thought he was snake-bit while making The Fortune Cookie. Right in the middle of filming, just as had happened with Kiss Me, Stupid, his comedic lead had a heart attack. Walter Matthau would not resume work on the film for five months, but,when recovered, continued with the role that eventually won him the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.

What inspired this farce about personal injury lawsuits was an incident where a sideline photographer was run over by a running back while Billy Wilder was watching a game on TV. Jack Lemmon's Hugh Hinkle collides with running back Luther Jackson (Archie Moore) of the Cleveland Browns, which lands him in the hospital with nothing but the spinal compression he suffered as a child. Hinkle's brother in law "Whiplash" Willie Gingrich (Matthau) declares it a tragedy and sues the Browns, the NFL, and CBS for Hinkle's old injury, which he plays up as new, putting Hinkle in a neck-brace and keeping him in the hospital for longer than necessary. For Willie. it's the money. For Hugh, it's the chance to get back his ex-wife (Felicia Farr) who left him to pursue a singing career. Things, of course, get complicated: the NFL's lawyers decide to fight, running Hugh through a battery of tests and hiring an unscrupulous detective (Cliff Osmond) determined to prove Hinkle's faking it by bugging his apartment and setting up movie cameras ("in Technicolor!") at the apartment across the street; Hugh hates the back-brace and the restriction put on him if the ex does come back; Jackson is beset by guilt and determined to help Hinkle get back on his feet—which he already can. Things can unravel very quickly, especially if Willie overplays it and oversteps his bounds, or if Hugh is agitated into activity.

The on-screen chemistry—one should say friction—between Matthau and Lemmon inspired one of the great movie duos since Astaire and Rogers...or Hope and Crosby...lasting decades, including future Billy Wilder movies.

Best line: "Unwed mothers? I'm for that!"

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) The plan was ambitious: Wilder wanted to make the ultimate Sherlock Holmes movie, a 3-hour "roadshow" picture (with intermission) featuring four stories (the idea being that they are hidden away in a bank deposit box only to be unearthed after the death of Holmes and Watson) previously unknown about The Great Detective. All were filmed over a six month shoot. But, United Artists insisted (given the poor performance of previous "roadshow" films and the movies' sudden "youth kick") on a truncated 2 hour version for theaters and demanded that two of the mysteries—"The Curious Case of the Upside Down Room" and "The Dreadful Business of the Naked Honeymooners"—as well as a flashback sequence of Holmes' school-days be cut, leaving only "The Singular Affair of the Russian Ballerina" and "The Adventure of the Dumbfounded Detective." All of the stories were to show an aspect of Holmes that was different from the "perfect calculating machine" known to readers of The Strand Magazine (where the Holmes stories were published), hence they're being locked away for decades. But, the entire skein of the film was to show a Holmes very much of the Victorian era who was soon to be out of touch with the advent of a new century, where values of love and war, were to become decidedly "unfair." And not logical.

And that the reason Sherlock Holmes may have no heart...is that it has been broken.

Robert Stephens was cast as Holmes because Wilder thought "he looked like he could be hurt" (Peter O' Toole was once considered, with Peter Sellers as Watson), with Colin Blakely as Watson and Christopher Lee (replacing George Sanders), who had once played Sherlock Holmes, as his brother Mycroft. Geneviève Page was cast as Gabrielle Valladon, who figures greatly in the final case. Stephens is exceptional, although his plummy dialect has led to the mistaken notion that Holmes is gay (he even claims it to get out of a predicament in the "Ballerina" episode) despite other evidence to the contrary and his quite-right "It's none of your business."

The film was meant to be a melancholy tragedy, like "Hamlet," but its tragedy played outside of theaters, as well. All the cut sequences demanded by the money-men are lost, tossed away and not to be recovered, although attempts have been made to piece together sequences from studio publicity shots and script notes. Like The Magnificent Ambersons, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes is one of the great "ghost" films, a shadow of what it could have been, given the complete context. We will never know. Damn studios and their "next fiscal quarter" thinking.

Best line: We all have occasional failures. Fortunately Dr. Watson never writes about mine.*****

Avanti! (1972) Based on a play by Samuel A. Taylor (who wrote Vertigo and the play Sabrina was based on), Avanti! is updated to the Nixon 70's by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond, as a slightly smutty comedy of manners, where a business-stiff, Wendell Armbruster, Jr. (Wilder muse Jack Lemmon) travels to Ischia, Italy to identify and claim the body of his father (Wendell Armbruster, Sr.). Turns out the son is a bit stiffer than the old man. He is shocked...shocked!...to find that dear old Dad, who supposedly went to Ischia for the therapeutic baths, was carrying on an torrid affair with a British mistress. This produces a prolonged hissy-fit—Lemmon excelled at these—where everything and everyone seems to be in a conspiracy to make claiming his father's body an unpleasant experience. The idea!

Avanti! (1972) Based on a play by Samuel A. Taylor (who wrote Vertigo and the play Sabrina was based on), Avanti! is updated to the Nixon 70's by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond, as a slightly smutty comedy of manners, where a business-stiff, Wendell Armbruster, Jr. (Wilder muse Jack Lemmon) travels to Ischia, Italy to identify and claim the body of his father (Wendell Armbruster, Sr.). Turns out the son is a bit stiffer than the old man. He is shocked...shocked!...to find that dear old Dad, who supposedly went to Ischia for the therapeutic baths, was carrying on an torrid affair with a British mistress. This produces a prolonged hissy-fit—Lemmon excelled at these—where everything and everyone seems to be in a conspiracy to make claiming his father's body an unpleasant experience. The idea!

The Fortune Cookie (1966) Billy Wilder must have thought he was snake-bit while making The Fortune Cookie. Right in the middle of filming, just as had happened with Kiss Me, Stupid, his comedic lead had a heart attack. Walter Matthau would not resume work on the film for five months, but,when recovered, continued with the role that eventually won him the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.

What inspired this farce about personal injury lawsuits was an incident where a sideline photographer was run over by a running back while Billy Wilder was watching a game on TV. Jack Lemmon's Hugh Hinkle collides with running back Luther Jackson (Archie Moore) of the Cleveland Browns, which lands him in the hospital with nothing but the spinal compression he suffered as a child. Hinkle's brother in law "Whiplash" Willie Gingrich (Matthau) declares it a tragedy and sues the Browns, the NFL, and CBS for Hinkle's old injury, which he plays up as new, putting Hinkle in a neck-brace and keeping him in the hospital for longer than necessary. For Willie. it's the money. For Hugh, it's the chance to get back his ex-wife (Felicia Farr) who left him to pursue a singing career. Things, of course, get complicated: the NFL's lawyers decide to fight, running Hugh through a battery of tests and hiring an unscrupulous detective (Cliff Osmond) determined to prove Hinkle's faking it by bugging his apartment and setting up movie cameras ("in Technicolor!") at the apartment across the street; Hugh hates the back-brace and the restriction put on him if the ex does come back; Jackson is beset by guilt and determined to help Hinkle get back on his feet—which he already can. Things can unravel very quickly, especially if Willie overplays it and oversteps his bounds, or if Hugh is agitated into activity.

The on-screen chemistry—one should say friction—between Matthau and Lemmon inspired one of the great movie duos since Astaire and Rogers...or Hope and Crosby...lasting decades, including future Billy Wilder movies.

Best line: "Unwed mothers? I'm for that!"

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) The plan was ambitious: Wilder wanted to make the ultimate Sherlock Holmes movie, a 3-hour "roadshow" picture (with intermission) featuring four stories (the idea being that they are hidden away in a bank deposit box only to be unearthed after the death of Holmes and Watson) previously unknown about The Great Detective. All were filmed over a six month shoot. But, United Artists insisted (given the poor performance of previous "roadshow" films and the movies' sudden "youth kick") on a truncated 2 hour version for theaters and demanded that two of the mysteries—"The Curious Case of the Upside Down Room" and "The Dreadful Business of the Naked Honeymooners"—as well as a flashback sequence of Holmes' school-days be cut, leaving only "The Singular Affair of the Russian Ballerina" and "The Adventure of the Dumbfounded Detective." All of the stories were to show an aspect of Holmes that was different from the "perfect calculating machine" known to readers of The Strand Magazine (where the Holmes stories were published), hence they're being locked away for decades. But, the entire skein of the film was to show a Holmes very much of the Victorian era who was soon to be out of touch with the advent of a new century, where values of love and war, were to become decidedly "unfair." And not logical.

And that the reason Sherlock Holmes may have no heart...is that it has been broken.

Robert Stephens was cast as Holmes because Wilder thought "he looked like he could be hurt" (Peter O' Toole was once considered, with Peter Sellers as Watson), with Colin Blakely as Watson and Christopher Lee (replacing George Sanders), who had once played Sherlock Holmes, as his brother Mycroft. Geneviève Page was cast as Gabrielle Valladon, who figures greatly in the final case. Stephens is exceptional, although his plummy dialect has led to the mistaken notion that Holmes is gay (he even claims it to get out of a predicament in the "Ballerina" episode) despite other evidence to the contrary and his quite-right "It's none of your business."