The Line King: The Al Hirschfeld Story (Susan Warms Dryfoos, 1996) Graphic artists, cartoonists, caricaturists do not make interesting subjects for documentaries. There's only so much you can do with somebody drawing a line—it's not interesting in and of itself because there's always that missing element, which is the magic that goes into it before pencil or pen hit paper. It's the brain at the other end of that pencil that makes it interesting and, if the documentary is doing its job, explains the magic that results in the line.

Fortunately, Al Hirschfeld was still alive at the time this was being recorded (he died in 2003, just shy of his 100th birthday). Stationed primarily in New York, he traveled the world in his life and settled back in The Big Apple, where he was a fixture in illustration, primarily for The New York Times art section, but also The New Yorker, Collier's, TV Guide, Rolling Stone, even creating a cover for an Aerosmith album. He did poster illustrations in the silent era, and his art was featured in postage stamps of those same silent comedians. A segment of Disney's Fantasia 2000—the "Rhapsody in Blue" segment—is based on his precise, serpentine, and almost embroidered style. The "genie" in the studio's animated version of Alladin is also based on his work.

Then, of course, there is the puzzle of it. Readers of The Times could count on two brain-teasers every issue—the crossword puzzle and Hirschfeld's drawings. After his signature of every piece would follow a number, that being the number of times he had hidden the name "Nina" (his only child's name) into the filaments of his pieces. It became a part of New York life along with thin pizza, egg creams, and the aggressively walking blind.At the time of first filming, his second wife—mother of Nina—was still alive. By the time filming was complete, she was dead and Hirschfeld talks about the effect on him. He would dutifully take a pad and paper to a theater before opening night to get a sense of the show, and begin the pain-staking work of getting it ready for publication.

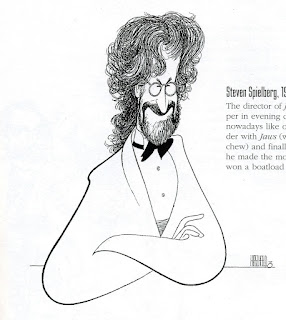

Susan Warms Dryfoos' film is grainy—a lot of it done in low light—with far too many interviews with NY hoi-polloi talking about Hirschfeld on various opening nights before it sinks in that he was an important part of any opening.It times you know they're talking of "the talk around town"—the reputation—than any first-person knowledge, but then, there's gotta be gossip. Those elements are catch-as-catch-can, with celebs and opening night regulars gushing, champagne in hand, about their personal experience with Herschfeld, before they're attention is pulled by some other bright light. The segments with the artist are less hectic, in low-light and lower energy, which is something of a relief. It puts in sharp contrast the hermetic life of a singular artist, even if his subjects are lit by klieg lights.Those are the parts that are gold, plus the looks at his work semi-contemporary or long past, several of which—of subjects that appear frequently on this site are below:

Three ages of Orson Welles...

No comments:

Post a Comment