The National Film Registry Class of 2021 is your typical roll-call of eclecticism—everything from a years-long effort created pixel by pixel to merely following Richard Pryor or Talking Heads around on the stage or merely just turning on a camera when the circus came to town.

It is the Registry's job—within the Library of Congress—to choose twenty-five films every year to house or preserve as a primary example of American produced film "deemed 'culturally, historically or aesthetically significant' that are

recommended for preservation by those holding the best elements for that

film, be it motion picture studios, the Library of Congress and other

archives, or filmmakers. These films are not selected as the 'best'

American films of all time, but rather as works of enduring importance

to American culture. They reflect who we are as a people and as a

nation." Films must be at least 10 years old to be considered—the films to be chosen in 2022 must have been released by 2011.

Here is a list of all the films in the Registry sorted by the year they were inducted starting in 1989. It can be easily toggled to show films in alphabetical order or listed by the film's release year.

Notes by the Library of Congress are in Arial font.

Mine are below them in the usual Verdana font in a darker color.

Chicana (1979) Producer/director Sylvia Morales created “Chicana,” a 22-minute collage of artworks, stills, documentary footage, narration and testimonies, to provide a counterpart to earlier film accounts of Mexican and Mexican-American history that all but erased women’s lives from their narratives. Centering on successive struggles by women from the pre-Columbian era to the present to combat exploitation, break out of cultural stereotypes, and organize for national independence, women’s education, and the rights of workers, “Chicana” resurrects an arresting array of proto-feminist icons to inspire Chicana feminists with role models from their cultural past. In 1977, Morales, an artist and cinematographer who had worked at KABC in Los Angeles and was enrolled in UCLA’s film school, became enthralled with a slide show created by Chicano Studies teacher Anna Nieto-Gómez that included a history of Mexican women of which Morales was unaware. With Nieto-Gómez’s support, Morales conducted additional research with Cynthia Honesto, hired composer Carmen Moreno to score the film and renowned actress Carmen Zapata to narrate it, shot documentary footage, and recorded interviews with Chicana activists Dolores Huerta, Alicia Escalante, and Francisca Flores to incorporate as voice-overs into the film. Acknowledged as a brilliant and pioneering feminist Latina critique, “Chicana” has served as a stepping stone for Morales’ distinguished career as a writer and director of acclaimed cable and public television documentary and fiction productions. UCLA has digitally scanned the best surviving picture sources for interim preservation purposes and hopes to turn this provisional work into a full restoration effort.

You see the DNA of public television documentaries (especially Ken Burns' output) in Chicana which takes on the subject of women in Latin culture. With only paintings, sculptures, and engravings to work with, Morales treats the still images with a movie director's eye, scanning, starting on a small detail, then expanding the image, giving it a story-telling incentive within the very frame. Only 23 minutes long, it never relents in its efforts to make still artifacts live and breathe.

Cooley High (1975)

NPR has called “Cooley High” a “classic of black cinema” and “a touchstone for filmmakers like John Singleton and Spike Lee.” Set in Chicago’s Cabrini Green housing project, “Cooley” is — at least at its start — a coming-of-age comedy about African American friends making the most of their halcyon high school days. But they soon find their lives and futures threatened when a small scuffle at a party escalates and projects them into a series of legal jeopardies. Though often compared to 1973’s “American Graffiti,” “Cooley” stands beautifully on its own thanks to its unique sensibilities, the taut direction of Michael Schultz and the incredible naturalistic acting styles of its entire cast — which included Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, Garrett Morris and Glynn Turman. Made on a small budget, “Cooley” would become one of the biggest critical and commercial successes of 1975. Retooled, “Cooley High” would also serve as the genesis for the successful TV sitcom “What’s Happening!!”

Lilly-white American International Pictures released Cooley High probably thinking they were getting another American Graffiti—low-budgeted/high-profiting with a best-selling soundtrack (a lot of which wasn't heard in its setting of 1964 Chicago). But, Cabrini Green ain't Modesto. And the hi-jinks of high schoolers there have different consequences than merely getting trapped in community colleges. Terrific acting by the professionals (especially Hilton-Jacobs, Turman, and Morris) and some great stuff from the amateurs. Cooley High starts out as a comedy with a serious undercurrent, and then sucker-punches you when you don't even know it. "For the dudes that ain't here"

Evergreen (1965)

Before co-founding The Doors and the band learning their craft in Los Angeles clubs such as London Fog and Whisky a Go, Ray Manzarek attended UCLA’s Film School, where he met fellow film student Jim Morrison. While at UCLA, credited as Raymond D. Manzarek, he created the student film “Evergreen,” about a jazz musician (Henry Crismonde) and his romance with an art student (played by Manzarek’s then girlfriend and future wife Dorothy Fujikawa). Manzarek was always a huge fan of the potential of cinema. He once noted, “Film is the art form of the 20th century, combining photography, music, acting, writing, everything. Everything that I was interested in all came together with that one art form.” In “Evergreen,” which has been called a “12-minute, West Coast, cool jazz, cinematic tryst,” one can definitely spot the influence of the French New Wave and filmmakers such as Jean Luc Godard. The film’s title reportedly comes from the Beat literary magazine, The Evergreen Review, and “Evergreen” features music by Herbie Mann/The Bill Evans Trio and the Jazz Crusaders. The location shots of mid-1960s Los Angeles comprise a magical time capsule of their own. Fujikawa sums up the impact of film on Manzarek and Morrison: “I think film informed his work and Jim’s work throughout their musical careers,” she said. “They always thought of their songs as cinematic expressions. They were always sort of little stories that were dramatic and told a story with music. In that way they were cinematic songs.” The film has been digitally restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

Student film directed by Raymond D. Manczarek about a fly-by-night jazz musician involved with an art student. No sync sound, but Manzarek overlays the hesitant, wait-and-see back and forth between the two over their relationship and it's apparent from every instance that she wants a relationship and he just wants to "hang out." A little too much Godard for me—four shots to show a guy getting out of bed? But, the story gets communicated with visuals even without the parallel dialogue.

Flowers and Trees (1932)

In the darkest days of the Great Depression, audiences welcomed a diversion when they went to theaters. Studios responded with Busby Berkeley musicals, risqué pre-Code films and trippy animations such as the Fleischer Studios’ Betty Boop cartoons. Those attending the 1932 premiere of Disney’s “Flowers and Trees” watched birds singing and trees awakening, all in spectacular hues: “Flowers and Trees” was the first three-strip Technicolor film shown to the public, and the dawning of a new era. The overwhelming response convinced Walt Disney to make all future Silly Symphony shorts in color and a few years later came features like “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.” Even today, the hand-drawn animation and vibrant Technicolor continues to charm and dazzle, showing new audiences the magic cinema can bring.

This marked when Disney became a success bringing out a Technicolor cartoon when everything was previously black-and-white. And whatever technical innovations Disney had made combining live action and animation went by the way-side when audiences saw the beauty of the Technicolor process. It was expensive, but Disney was never one to scrimp on the budget when it had a noticeable effect on the art. Still a bit crude with little of the sophisticated artistry the Disney crew would bring to nature, and some of the sync with the patched together musical track doesn't quite "hit." But, it's pretty sophisticated to tell a story with words and pictures without any descriptors.

The Flying Ace (1926)

The Norman Film Manufacturing Company of Jacksonville, Florida, was an important producer of “race films,” movies made specifically for Black audiences. Although owned by Richard Norman, a white man, the studio’s films tended to portray a world in which whites, and thus racism, was completely absent and Black relationships are at the center of the story. “The Flying Ace” is an excellent example, a romance-in-the-skies drama with a compelling cast, including Kathryn Boyd playing a character inspired by Bessie Colman, the first African American woman pilot.

A "whodunnit" involving the theft of $25,000 and the disappearance of the payroll master from a railway depot, offers red herrings, two fist-fights, and chases between a car and a bicycle and two planes—one of them on fire! The local police look to arrest the station master who can't recall what happened at the time of the robbery and it's up to Flying Ace (and former railway detective) Capt. Billy Stokes (Laurence Criner) to get to the bottom of it, and win the heart of the station master's daughter. Some rather clever plot devices and the most tricked-out crutch you ever saw.

Hellbound Train (1930)

This surreal and mesmerizing allegorical film by traveling evangelists James and Eloyce Gist is an important and, until recently, overlooked milestone in Black cinema. Painstakingly reassembled from more than 100 reels of 16mm at the Library of Congress by filmmaker S. Torriano Berry, this early example of independent community filmmaking is a fierce and entertaining condemnation of sinfulness with Satan portrayed as a tempting conductor. The Gists showed this silent film in Black churches accompanied by a sermon and religious music.

How the devil's heart does rejoice! For those not taking notes during the presentation, the compartments on the "Hellbound Train" are: Car 1: dance; Car 2: drunkeness; Car 3: jazz music; Car 4: thieves, crooks and grifters; Car 5: murderers and gamblers; Car 6: backsliders, hypocrites, and used-to-be church members; Car 7: liars. Each segment has illustrative examples of how such miscreance affects the lives of the common-folk.

Jubilo (1919)

In the third film of his illustrious motion picture career, humorist and cowboy philosopher Will Rogers enacted the easy-going, likable tramp Jubilo, named after a Civil War song in which enslaved people using stereotypical dialect celebrate their hoped for emancipation. Theater organists and pianists no doubt played the tune repeatedly throughout the picture, and for years afterwards, it became a signature song for Rogers, a multiracial member of the Cherokee nation who often portrayed a comic trickster common in both African American and Native American cultures. Despite its predictable plot, “Jubilo” was distinguished by the uniquely human character Rogers created and the title cards he authored that gave national audiences a taste of the topical remarks he would casually toss off from the stage as he entertained New York audiences with his roping and horseback riding tricks. One card, appearing after his character spends a night trying to fix an automobile, satirizes Henry Ford’s recently unsuccessful political ambitions with the line, “No wonder he wasn’t elected to the Senate with everyone owning one of these.” Reviewers praised Rogers’ “wonderfully natural creation” and “rugged sense of humor,” and a few years later, director Erich von Stroheim commended Rogers’ pictures for their character-driven realism, a desired quality he found otherwise lacking in most of Hollywood’s more plot-dominated productions. The film is preserved by the Museum of Modern Art.

Will Rogers seems born to be in front of the camera as evidenced by this silent film. With his relaxed stance and putty face (that the camera loves), everything going through his mind is communicated to the audience. In contrast to the theatricality of the other performers, Rogers is a natural and even the intimacy of the camera never catches him being any less than genuine.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

In “The Long Goodbye,” Elliott Gould, star of such counterculture classics as “M*A*S*H*” and “Little Murders,” brings Raymond Chandler’s iconic depression-era detective Philip Marlowe into a contemporary Hollywood-infused setting where his moral compass seems anachronistic. Robert Altman directed this richly complex, iconoclastic and highly entertaining detective mystery with a script by Leigh Brackett, who had co-authored the screenplay of the film noir classic “The Big Sleep,” in which Humphrey Bogart epitomized Chandler’s hard-nosed individualist hero for an earlier generation. The inspired, non-traditional cast, some of whom Altman encouraged to create their own characters and lines, includes Sterling Hayden, Jim Bouton, Nina van Pallandt, Mark Rydell and Henry Gibson. Shot by pictorially-inclined cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond near the beginning of his illustrious career, “The Long Goodbye” employs unsettling, ever-moving camerawork and compositions that masterfully utilize the transparent and reflective surfaces common in southern California modernist architecture. Altman and Zsigmond’s technique allows viewers to eavesdrop on a corrupt world of trivial pursuits and shocking violence that has left many of its inhabitants impotent, indifferent or deeply scarred. Gould’s repeated signature line, “Its OK with me,” resonates throughout until Chandler’s shining knight ends the film with a morally ambiguous resolution. Zsigmond won the National Society of Film Critics’ award for best cinematographer for his work in “The Long Goodbye.”

Leigh Brackett, who had co-written the screenplay of The Big Sleep—featuring Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe—wrote a screenplay for The Long Goodbye in the 1970 with the idea that Elliott Gould would play Marlowe and the script languished. Both Howard Hawks (who'd directed the 1945 Big Sleep) and Peter Bogdanovich passed on directing it. Bogdanovich suggested Altman, Altman liked the script (especially Brackett's changed ending), liked Gould and took on the job. And, surprisingly, it works. It's a shock to anybody with any history with Marlowe, but a 1973 Marlowe would be woefully out-of-place in the hippy-dippy L.A. of the 1970's. Something had to give and the moral corruption of The Big City that Marlowe usually waded in wasn't going to be it. Some of Altman's (and Zsigmond's) best work navigating the sliding glass partitions of modern L.A.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

Director Peter Jackson kicked off his epic trilogy of films of J.R.R. Tolkien’s beloved oeuvre with this 2001 film. From its visually stunning depiction of Middle-Earth to his large, expert, all-star casting (Elijah Wood, Ian McKellen, Liv Tyler, Viggo Mortensen, Sean Astin, Cate Blanchett, Hugo Weaving, John Rhys-Davies, Orlando Bloom, Christopher Lee and Andy Serkis), Jackson and company created a respectful, literate adaptation of one of the world’s most cherished series of written works. Key to making all this magic work and the story of Hobbits surprisingly human are the heartfelt performances (led by Wood as Frodo and McKellen as Gandalf). The combination of magnificent production values and scenes filmed in spectacular New Zealand locations made this a must-see, particularly on wide screens in a cinema.

Tolkien's Ring Trilogy had been a cultural touchstone since the 1960's, but the idea of doing a film of the story was so daunting that no one wanted to touch it. Oh, The Beatles thought about playing hobbits in a film adaption, but that never went anywhere and Ralph Bakshi made an animated version of the first half in 1978. After that, Tolkien's tale was picked away at by other authors and film-makers...until Peter Jackson acquired the rights and set himself the herculean task of making movies of the three books simultaneously. And it's a wonder. And a bit of a miracle. Epic in scope, but intimate in its characterizations—Jackson and fellow screenwriters Fran Walsh and Philipa Boyens did encyclopedic work on Tolkiens writings—The Fellowship of the Ring was a miracle of world-building (primarily in New Zealand) and design (set up by Jackson's WETA group), superbly cast and dynamically executed. It whet audiences' appetites for the continuations which matched and exceeded the maker's original intentions.

The Murder of Fred Hampton (Howard Alk, Mike Gray, 1971)

This documentary profiles the final year in the life of Fred Hampton, the 21-year old charismatic leader of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party. The first half shows Hampton making speeches, passionately urging armed militancy, as well as non-violent advocacy, to confront poverty, protest police brutality and build coalitions to broaden the message of the party from “Power to the People” to “All power to all people.” During production, Hampton and Mark Clark were killed in a police raid, and the film transitions to an investigation of their deaths and the motives of authorities local and beyond. The New York Times, while admitting the film had flaws and certainly was unabashedly biased, assesses that the footage and TV documentation “constitute a remarkable, if uneven, case history. It is, in sum, an unleavened indictment of Edward V. Hanrahan, the Illinois state's attorney, the policemen in the raid and the Chicago political establishment." The film was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

The true-life events that inspired Judas and the Black Messiah. It starts out as a documenting of Hampton's efforts and activities serving the Chicago community as head of the local Black Panther party. At 52:38, the film goes from Hampton leading a chant of "I am...a revolutionary" to the bloody mattress on which Hampton was murdered. Alk and Gray had access to the unsecured apartment soon after the police raid that killed Hampton and Clark and documented the extensive damage. Tours were arranged for neighborhood activists to view the address, disclaiming the official accounts of the Chicago police and the Cook County State's Attorney. The footage was used as evidence in the grand jury indictment of the State's Attorney as well as a subsequent civil suit.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

The great horror maestro Wes Craven, as both writer and director, gave a generation of teens (of all ages) terminal insomnia with this imaginative and intense slasher scare fest. Freddy Krueger (played by soon-to-be legend Robert Englund) is the burn-scarred ghost of a psychopathic child killer, now returned to haunt your dreams and take his revenge! Heather Langenkamp stars as the heroic Nancy, who figures out who Freddy is and must be the one to stop him. Also in the cast: Johnny Depp, John Saxon, Ronee Blakley and Charles Fleischer. Made on a budget under $2 million, “Elm Street” became a box office sensation and has inspired numerous sequels (including a film that pitted Freddy against Jason of the “Friday the 13th” films), a 2010 remake, a TV series, books, comic books and videogames, making it one of the most successful film franchises in the history of any cinematic genre. The film established New Line Cinema as a major force in film production with some calling New Line “The House That Freddy Built.”

“O God, I could be bounded in a nut shell and count myself a king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams,” says Shakespeare. "Morality sucks!" rejoins Glen ("introducing Johnny Depp"), the boyfriend of Nancy Thompson (Heather Langenkamp, who really was 20 years old at the time of filming). Seems the kids of the parents who killed child murderer Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund) are having nightmares they never wake up from, leaving behind very messy bedrooms. Craven was still making low-budget horror, but retained that goofy sense of humor—stopping Freddy with a sledge hammer wired to the door?—and just when you think he's treading the same "bad kids get killed" scenario, he up-ends it and blames the parents. One genuinely good shock with several attempts.

Pink Flamingos (1972)

The movie poster tells the story: drag icon Divine, resplendent in a red gown, hair and makeup at glorious extremes, perched on a cloud and brandishing a pistol, beneath the tagline “An Exercise in Poor Taste.” Baltimore favorite son John Waters’ delirious fantasia centers on the search for the “filthiest person alive” and succeeds, but not before having a lot of outrageous fun along the way. This cult classic has been embraced by a generation of filmmakers and is considered a landmark in queer cinema.

As they say in The Producers: "Well! Talk about bad taste!" John Waters' Pink Flamingos takes that in all meanings of the phrase. The third film in his "Trash Trilogy" Waters funded it ($10,000) with donations and, as he had with his previous films, managed to repay the investors and still make a profit, to make his next film. If there is some aspect of deviation with "-ology" at the end of it, it's in this movie, and as a result, on its initial release, it was banned in some U.S. districts and certain countries. However, it became a staple on the Midnight Movie circuit, proudly displaying this blurb from The Detroit Free Press: "Like a septic tank explosion, it has to be seen to be believed."

Requiem-29 (1970)

UCLA's Ethno-Communications Program's first collective student film had intended to capture the East Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam, Aug. 29, 1970, but the film turns into a requiem for slain journalist and movement icon, Ruben Salazar. The film shows footage of the march, the brutal police response and resulting chaos interspersed with scenes from the rather callous and superficial inquest. Filmmakers attached to the project have confirmed that the original elements for the film disappeared over 40 years ago. The UCLA Film and Television Archive has facilitated a 4k scan of the surviving faded 16mm print for preservation purposes and hopes to turn this provisional work into a full restoration effort.

These are the elements as they exist today—the time-code stamp is imprinted in the video.

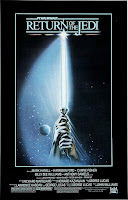

Return Of The Jedi (1983) aka Star Wars: Episode VI - Return of the Jedi The original “Star Wars” trilogy reached its first apex with this film, the third release in the “a galaxy far, far away” trifecta. Directed by Richard Marquand, from a story by, of course, George Lucas, “Jedi” launches Lucas’ original, legendary characters — Luke, Leia, Han Solo, C-3PO, R2-D2 and others — on a series of new adventures, which takes fans from the planet of Tatooine to the deep forests of Endor. Populated by intriguing new characters — including Ewoks and the gluttonous Jabba the Hutt — and filled with the series’ trademark humor, heart, thrills and chills, “Jedi,” though perhaps not quite up to the lofty standards of its two predecessors, still ranks as an unquestioned masterpiece of fantasy, adventure and wonder.

George Lucas was still the writer-producer for the third film in his "Star Wars" series; Richard Marquand was hired to direct Jedi—although David Lynch was considered and what a version THAT would have been. Lucas had a lot of material to finish up: he had set up a great cliff-hanger—as in the movie-serials he was emulating—and Han Solo had to be rescued from Jabba the Hutt (which could be done as Harrison Ford agreed to appear in the third film; the story was expanded to include The Emperor Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid, in what would become a decades-long commitment) and the story of Luke's parentage and of the mysterious Force "other" that had been mentioned in The Empire Strikes Back had to be resolved; Luke's interrupted Jedi training needed to be concluded with Yoda; the Luke-Leia-Han love triangle needed to be dispensed with; oh, and (while we're "a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away") the Galactic Empire had to be defeated. No pressure. There was so much story-work to be done that Lucas recycled original plans from Episode IV—another Death Star, an indigenous people would take on The Empire (but, instead of Wookiees, as in the original film's initial scenario—before Lucas cut it for budget reasons—they were shrunk and became Ewoks). The results were somewhat reduced, as well. The script's a bit clunky with exposition (and Ben Kenobi is exposed as a manipulative liar "from a certain point of view"), Ford is relentlessly mugging...and I've never bought the conversion of Darth Vader/Anakin Skywalker (except that it had to happen). And the Ewoks? Well, the entire series was less sophisticated than people mis-remembered, and Lucas would earn their wrath when he continued in that vein in Episodes I-III. Still, it was a great exercise in playing with great stakes while making things up on the fly. And, as Roger Ebert supposed in his review of The Phantom Menace, if this had been the first film in the series, we would have been amazed.

Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979)

Very few other stand-up comedy stars had ever taken their sets to the big screen and presented themselves and their comedic vision so fully, and in a manner so raw, so unadorned, and unedited. The great Richard Pryor did it four times. This riotous performance, recorded at the Terrace Theatre in Long Beach, California, is quintessential Richard Pryor: shocking, thought-provoking, proudly un-PC and, undeniably hilarious. Already, a legend in the world of stand-up comedy, this film — as straightforward in its title as Pryor is in his delivery — cemented Pryor’s status as a comedian’s comedian and one of the most vital voices in the history of American humor.

"Jesus Christ! Look at the white people coming back (from the bathroom!)" Pryor starts his concert. "This is the fun part for me—white people come back from intermission and find out n______'s have stole their seats!" "Well, we're sittin' here now, m_____-f______'s!" Pryor is instantly hilarious and everything can be turned into subject matter that kills. "And I am really personally happy to see anybody come out and see me, right, especially as much as I done f____'d up this year!" Pryor proves himself a crack stand-up even when lying down and keeps the laughs in a steady stream. The artistry is his, as the crew are basically following him, staying out of his way, and keeping the cameras loaded with film.

Ringling Brothers Parade Film (1902)

Recently restored by the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, this 3-minute actuality recording of a circus parade in Indianapolis in 1902 accidentally provides a rare glimpse of a prosperous northern Black community at the turn of the century. African Americans rarely appear in films of that era, and then only in caricature or as mocking distortions through a white lens. Actuality films indelibly capture time and place (fashions, ceremonies, locations soon to disappear, behavior at large events and the key daily routines of life), sometimes unexpectedly so as in this delightful gem.

Selena (1997)

In her first major film role, Jennifer Lopez’s performance in “Selena” captures the talent, beauty, youthful spirit and many of the reasons why Selena Quintanilla-Pérez was so beloved and on her way to becoming one of the biggest stars in the world. Already the first and most successful female Tejana music singer, Selena’s growing popularity in both Mexican and American music and fashion paved the way for many of today’s biggest pop stars, including Jennifer Lopez herself. Directed and written by Gregory Nava, “Selena” is the official autobiographic film authorized by the Quintanilla family. Selena’s father, Abraham Quintanilla, serves as a producer and is played by Edward James Olmos in the movie. Olmos has said that there were moments on the set when Selena’s father would excuse himself and quietly cry in the corner because of the fresh emotions of her death and because many events were so accurately portrayed. The final montage of the movie features real footage and photos of Selena’s life.

Nava starts out his film with Selena's biggest concert in the Houston Astrodome February 26, 1995. Just over a month later, she would be dead. Nava handles the concert performances with quick-cutting and sometimes split-screens while Jennifer Lopez lip-syncs Selena's recordings...the syncing is sometimes off (probably due to editorial choices of song-sections) and Nava's strategy helps. It's Lopez's first film role and she's amazing in it, more than fulfilling the Quintanilla family's perfect image of Selena—but, when footage of Selena is played at the end, you're still startled at Lopez's accuracy. Although she grounds the movie, one has to say that Edward James Olmos' is the performance that holds the film together as the driven father who took his own frustrated music goals and turned them into a viable ground-breaking family act that has to be "more Mexican than Mexicans and more American than Americans—it's hard to be Mexican American!" It's a movie that makes you feel the loss.

Sounder (1972)

Cicely Tyson and Paul Winfield shine as a sharecropper couple trying to get by during the Great Depression in the rural South. Directed by Martin Ritt, the story follows the family’s pre-teen son (played by Kevin Hooks) as he is thrust into becoming the "man of the family.” Critic Stanley Kaufman wrote that Ritt "is one of the most underrated American directors, superbly competent and quietly imaginative," and this understated brilliance and love for the humanity of ordinary folks is on glorious and moving display in “Sounder.” Taj Mahal both acted in the film and composed the score.

"Oh my God" she whispers. "Nathan!" I start crying as soon as I hear that—although the tears form when the dog perks up. There is something primal about Cicely Tyson's performance in this scene—but she's amazing in the whole thing—and director Martin Ritt (who'd been directing a few years) had the taste and the decency to shoot it the way he did. We're witness, but not part of it, there's no swelling of strings, no overt manipulation. So much of it is shot in long lenses and great distances. The whole movie is understated, but masterfully crafted, and one of those movies I can watch again and again and still be awed by it. Not because of the lighting and the camera angles and the showmanship...but the restraint of it, a director just letting the story...and inspired actors...be.

Stop Making Sense (1984)

The seminal New York-born rock/new wave/punk/post-punk band, the Talking Heads, were captured at the height of their powers in this now iconic concert film. Led by their charismatic frontman David Byrne, the Talking Heads tear through some of their most famous songs in this tight 88-minute performance. Selections include: ”Once in a Lifetime,” “Burning Down the House,” “Psycho Killer,” “Life During Wartime” and, from Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth’s side project, the Tom Tom Club, a spirited rendition of “Genius of Love.” Nearly as inventive visually as it is sonically, the film is directed by Jonathan Demme who, wisely, keeps his camera tightly focused on the stage, leaving the music and band members (and the members’ own unique theatrics) to speak completely for themselves. Leonard Maltin has called “Stop Making Sense,” “one of the greatest rock movies ever made.” It is infectious and the quintessential get-up-and-dance experience.

"Does anybody have any questions?" No. None at all. Because, even taken at face value, Demme's recording of the "Stop Making Sense" tour is fun (three performances that were cut together and it's almost seamless), with ear-worm songs that stay with you for days and, on closer analysis, reveal themselves to be intricate interlocking pieces that flow into a dance-inducing whole. Byrne's ability to boil down performance to simple moves—at one point he just runs around the stage to keep up (and boil off) the energy, rather than some pretentious dance-stomp to "sell the song" (as one might see with another band). Even if you're not a slavish devotee, Stop Making Sense brings a smile to your face and a tap to the feet, as well as an appreciation for the work that goes into making music.

Strangers on a Train (1951)

Wildly imitated but never topped, this riveting 1951 Hitchcock classic tells of two men who, having met on the titular train, hatch a plan to “swap” murders, each killing someone the other knows and, thereby, giving the other an air-tight alibi. Farley Granger thinks the whole plan a joke while Robert Walker subsequently commits a murder and demands Granger keep his part of the deal. This thriller contains strong supporting performances by Marion Lorne, Ruth Roman and Patricia Hitchcock and, of course, by the Master of Suspense’s signature, extraordinary visuals: from a tense tennis match to a wild, out-of-control merry-go-round finale, with a monogrammed cigarette lighter serving as one of Hitchcock’s trademark “MacGuffins.”

With source material from Patricia Highsmith ("The Talented Mr. Ripley"), adapted by Whitfield Cook, Czenzi Ormonde, Ben Hecht, and (gasp!) Raymond Chandler, Hitchcock's tale of a psychopath (Robert Walker) proposing to a tennis-pro (Farley Granger) of "switching murders" (and acting on it), Strangers is a solid Hitchcock thriller, one of the ones that really, really works with no flab and creates a paranoid nightmare from beginning to end. Add to that some darkly witty dialog, a couple of cracker-jack visual touches (like the one below) and a climax on a runaway merry-go-round and you have an off-beat Hitchcock thriller still remarkably on-beat. One of the Master of Suspense's deviously conceived traps.

WALL•E (2008)

Wowing critics and audiences of all ages alike, Pixar Animation Studios has had an unrivaled run of cinematic masterpieces, including the marvelously unique WALL•E (2008). Fresh off the monster hit “Finding Nemo” (2003), director Andrew Stanton created an incredible blend of animation, science fiction, ecological cautionary tale, and a charming robot love story. It is the tale of a lovable, lonely trash-collecting robot, “WALL•E” (standing for Waste Allocation Load Lifter: Earth Class), who, one day, meets, quite literally, his Eve. A triumph even by Pixar standards, the film uses skillful animation, imaginative set design (and remarkably little dialogue) to craft two deeply affecting characters who transcend their “mechanics” to tell a universal story of friendship and love. Comic relief is provided by M-O (Microbe Obliterator), a truly obsessed neat freak cleaning robot ever on the search for “foreign contaminants.” The film won the Oscar in 2009 for Outstanding Animated Feature.

WALL•E was the last of the "original concept" stories (written down on a napkin) that comprised the first story session conference over a dinner among the Pixar creators. One can see why they saved it for last. Complex in its story-telling—done in large part with no dialog—and requiring a photo-realistic sense that would sell its concept of a trash-infested Earth 700 years after its original inhabitants went off-world on gigantic galactic cruise-liners, it needs that approach to sell a world of Aztec-shaped pyramids of compacted trash that dwarf skyscrapers to sell the concept of a world over-consumed. The animators even over-layer things with a fine layer of exhaust haze and dust-storms that give things a sense of scale. When WALL•E's working exile is interrupted by the arrival of Eve (Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) sent back to Earth to scan for any signs of life, he shows her his prize of the things he's been collecting for his own amusement—a lone seedling. This kicks in her auto-responses and she takes the twig back to Earth's doughy descendants forcing WALL•E to follow her—he has fallen in love. Funny, charming, with a Lubitschian melancholy as spice, WALL•E recalls a high-tech version of Hollywood romantic comedy, with just a touch of "Spare-partacus"

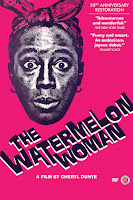

The Watermelon Woman (1996)

This is the first feature film by Cheryl Dunye, one of the most important of African American, queer and lesbian directors. The director herself stars as Cheryl, a 20-something lesbian struggling to make a documentary about Fae Richards, a beautiful and elusive 1930s actress popularly known as The Watermelon Woman. The title of the film is a nod to Melvin Van Peebles’ 1970 “The Watermelon Man.” In “Watermelon Woman,” the aspiring director explores the erasure of Black women from film history, as it dovetails with her own exploration of her identity as a Black lesbian seeking love and validation. The film was a new queer cinema landmark. Of why she became a filmmaker, Dunye, during a 2018 interview at Indiana University, recalls attending a screening of “She’s Gotta Have It” in Philadelphia and the follow-up Q&A with director Spike Lee. Many in the audience planned to slam Lee over his controversial sexualized female protagonist. Lee answered that it was his film and he will represent the characters as he wishes, and he noted that if you wanted to change how African American women are represented, go make your own film. Dunye took that suggestion, and we are the richer for that decision. The film was restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive.

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)

Despite a memorable, long-running feud, two of classic cinema’s greatest grand dames united for the first, and only, time in this 1962 horror dark comedy which delves into the redundant worlds of fading film stardom and the macabre. Directed by Robert Aldrich, “Baby Jane” recounts the tattered lives of two now aged former stars: the dominating Baby Jane (played by Bette Davis) and her disabled sister Blanche (played by Joan Crawford) as they live out their lives in a decaying mansion, loathing one another as Jane torments Blanche. The film, even today, remains vivid and often uncomfortably terrifying. Along with showcasing two powerhouse actresses, “Baby Jane” ignited — for better or worse — the “psycho-biddy” subgenre: films featuring older female stars in similar, grand ghoul enterprises.

A sick, twisted version of a Hollywood Tragedy story, directed with malice towards everyone by Robert Aldrich and taking advantage of two stars who loathed each other so much they'd sabotage the project just to get back at each other. The thing is, while Bette Davis and Joan Crawford were strategizing how to steal the picture from each other, they were also making the movie far more entertaining than its original source to the point that they started reflecting the twisted relationship between the two fictional fading film-stars. And why not go for broke? Gloria Swanson had revived her career with Sunset Boulevard, and this film—so over-the top in going places Swanson wouldn't even go—kept both actresses in the spotlight for their daring and bravery...and frankly, their subsuming of vanity in their separate portrayals.

Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1987)

In 1982, Vincent Chin, a 27-year old Chinese American, was beaten to death with a baseball bat in Detroit by two white auto workers. Detroit during that period was a cauldron of racism against Asian Americans, amid the decline of the U.S. auto industry as Americans elected to buy Japanese cars. Those who killed Chin likely assumed he was Japanese. In the end, the two men were found guilty of manslaughter but given probated sentences and served no jail time. Directors Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña’s Academy Award-nominated documentary examines this appalling miscarriage of justice and the multiple issues it raises including how irresponsible media can increase the risk of violence against ethnic minority communities. According to co-director Choy, the film’s key elements involve: (1) this being one of the very first civil rights case involving an Asian American (2) how the case mobilized many Asian Americans in the country, (3) Though the Chin side lost the case but also raised an incredible amount of consciousness about the civil rights issue involving all people of color and (4) The ultimate question of why the system failed and what have we learned from this? The film was restored by The Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation.

The recent assaults on the AAPI community in recent months has only emphasized what this film makes explicit—Europeans are too stupid to know the difference between Japanese and Chinese and Korean and Vietnamese or Thai. The perpetrator of Vincent Chin's murder...and it was murder—and premeditated as the guy and stepson drove around looking for him with the aim to bash him with a baseball bat after a bar altercation—blamed Chin (who was Chinese) for the Detroit auto firm downturns due to Japanese competition. What is particularly sickening is that the perp thought the murder was "preordained" (as he says in the clip) and took no responsibility for beating a man to death with a baseball bat. The full film was available on Vimeo until the director petitioned to have it removed once it was voted into the NFR. In the meantime, there is this snippet:

The Wobblies (1979)

“Solidarity! All for One and One for All!” Founded in Chicago in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) took to organizing unskilled workers into one big union and changed the course of American history. This compelling documentary of the IWW (or “The Wobblies” as they were known) tells the story of workers in factories, sawmills, wheat fields, forests, mines and on the docks as they organize and demand better wages, healthcare, overtime pay and safer working conditions. In some respects, men and women, Black and white, skilled and unskilled workers joining a union and speaking their minds seems so long ago, but in other ways, the film mirrors today’s headlines, depicting a nation torn by corporate greed. Filmmakers Deborah Shaffer and Stewart Bird weave history, archival film footage, interviews with former workers (now in their 80s and 90s), cartoons, original art, and classic Wobbly songs (many written by Joe Hill) to pay tribute to the legacy of these rebels who paved the way and risked their lives for the many of the rights that we still have today. The film was restored by the Museum of Modern Art.The film can be viewed for free here: https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=375331150736625&id=898262400235836&_rdr

No comments:

Post a Comment