I don't like those: they're rather arbitrary; they pit films against each other, and there's always one or two that should be on the list that aren't because something better shoved it down the trash-bin.

So, I came up with this: "Anytime" Movies.

Anytime Movies are the movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, sometimes it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again (and again!) and never tire of them. There are ten (kinda). They're not in any particular order, but the #1 movie IS the #1 movie.

I’m very suspicious of patriotism (I always recall the "last resort of a scoundrel" remark), yet nothing moves me so much like a movie extolling the virtues of America. The promise "to form a more perfect Union," as it was outlined in The Constitution, as opposed to lining people's pockets, or to lionize the undeserving, or to maintain the status quo because it's comfortable.

Anybody who's fought for this country knows it's not comfortable (and if they did, they were promoted too soon!)

It wasn’t until I was voting on the Emmy’s that I sat down and watched TV's “The West Wing.” I figured it was going to be a vapid “America-Love It or Leave It” tract (starring Rob Lowe), even if it did have Martin Sheen playing the President, in which case, I could leave it. But TWW was a serious look at government work—its glories and disappointments, the combination of ego and sacrifice. It could criticize individuals and “ideology for ideology’s sake,” but one thing it never ever criticized was the idea of Public Service, no matter what side of the aisle it was on. At the same time the country is being run by crooks specializing in an institutionalized form of bribery and graft, there is an infrastructure of people for whom government service is a sacred trust (well, there’s gotta be ONE!) “The West Wing” paid tribute to that corps of people wherever they might be, week after week, and it made for refreshingly positive TV. It also made for a refreshing look at our nation as it stands.

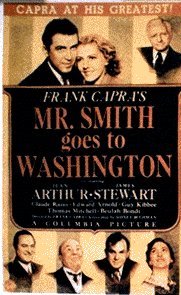

And so, too, does Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Made in 1939, it plays like it was written yesterday. When I saw it for the first time—right after “Watergate”—I found it amazingly prescient. But, no, it was talking about its own times. The problems just keep re-occurring again and again. And again. Whoever doesn’t know history is doomed to repeat it, and with every fresh crop of people governing, they’ll keep making the same mistakes. Maybe they think they’re unique. Maybe they just don’t know history. They say that if you keep making the same mistake over and over, it’s a sign of insanity. Well, psychology never factored in term limits.

It wasn’t until I was voting on the Emmy’s that I sat down and watched TV's “The West Wing.” I figured it was going to be a vapid “America-Love It or Leave It” tract (starring Rob Lowe), even if it did have Martin Sheen playing the President, in which case, I could leave it. But TWW was a serious look at government work—its glories and disappointments, the combination of ego and sacrifice. It could criticize individuals and “ideology for ideology’s sake,” but one thing it never ever criticized was the idea of Public Service, no matter what side of the aisle it was on. At the same time the country is being run by crooks specializing in an institutionalized form of bribery and graft, there is an infrastructure of people for whom government service is a sacred trust (well, there’s gotta be ONE!) “The West Wing” paid tribute to that corps of people wherever they might be, week after week, and it made for refreshingly positive TV. It also made for a refreshing look at our nation as it stands.

And so, too, does Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Made in 1939, it plays like it was written yesterday. When I saw it for the first time—right after “Watergate”—I found it amazingly prescient. But, no, it was talking about its own times. The problems just keep re-occurring again and again. And again. Whoever doesn’t know history is doomed to repeat it, and with every fresh crop of people governing, they’ll keep making the same mistakes. Maybe they think they’re unique. Maybe they just don’t know history. They say that if you keep making the same mistake over and over, it’s a sign of insanity. Well, psychology never factored in term limits.

Mr. Smith… is the story of a local youth leader who is appointed to the Senate after the incumbent suddenly dies. This runs afoul of the state’s political machine that ran that late senator as well as the state's senior Senator, Paine (Claude Rains)—who just happens to be an idol of the new senator’s. But, "The Machine" lets it happen, as Smith is a yokel, and their boy, Paine, will be able to keep him in line.

It wouldn’t work if director Frank Capra didn’t have tall awkward Jimmy Stewart—not James, Jimmy—whose every stammered syllable bespoke humility. But get him talking about America or Liberty of The Capitol Dome and the stutter disappears in a fervent stage whisper that trails off in awe. Mr. Smith isn’t sure of himself, but he’s sure sure of the Country.

And Washington, D.C. is just the place to shake him up with a few lashes of the Beltway. Stewart could be frustratingly folksy, but for Capra (and for Hitchcock and Anthony Mann) he could be unnervingly vulnerable and, at the other end of the bi-pole, dramatically unhinged. The last act of Mr. Smith…—the filibuster against false charges of graft—features Stewart in both phases. At one point, he's knee-deep in political hate-mail, clutching it in his hands and looking skyward like Jesus at Gethsemane. Then a few short paragraphs about “lost causes” later, he’s at his most defiant. “You think I’m licked! You ALL think I’m licked!!” That was his Oscar-winning performance, not the next year’s The Philadelphia Story where the “cynical reporter” bit just didn’t wash with someone who looked so homespun. The filibuster scene always brings a lump to my throat, and it’s not sympathy pains for Stewart’s frayed larynx.

Now, I’ve read the original screenplay to “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” It ends with a big parade honoring the completely vindicated Smith, surrounded by his boy-rangers, supported by the woman-he-loves (Jean Arthur, again, who manages to make her extraordinarily jaded Senate Aide adorable, even when she’s at her worst—and she has a great drunk scene with Thomas Mitchell. Hmmm, Thomas Mitchell, again). Why, even the disgraced Senator Paine is being lionized in the sequence. Oh, it’s just so sweet, your eyes could roll back in their sockets and jam and stick that way. As Arthur’s Miss Saunders tipsily says in the film, “Nah, I can’t think of anything more shappy!” “Capra-corn” is what the very self-aware director called it.

So, he cut it. Orson Welles has said: "If you want a happy ending that depends, of course, on where you stop your story." Capra leaves his story’s ending ambiguous. Oh, you could call the riotous goings-on at the end a Happy Ending—but all of Paine’s Senate pals are trying to calm him down, telling him it’s okay…everything’s all right, we're still on your side. The only solace Jefferson Smith is granted is in the sympathetic smile from the Vice-President (played by John Ford’s silent cowboy film-star Harry Carey) before he collapses in a heap of his enemy’s mass-generated letters. The movie "celebration" has all the weight of an Al Gore victory celebration on Election Day 2000--a case of premature exaltation. But nothing's been solved. No one's been cleared. Nothing has been decided. There is just misunderstanding and confusion. Carey leans back and has a chaw while the chaos of Democracy continues unabated. It may not be a "happy" ending, considering the sequence that was shelved. It may not even be a dramatically satisfying ending. But it is representative of the loud, messy process that turns the gears of Democracy.

However slow-moving, however off-course, they still turn.

Anytime Movies:

Chinatown

American Graffiti

To Kill a Mockingbird

Goldfinger

Bonus: Edge of Darkness

Chinatown

American Graffiti

To Kill a Mockingbird

Goldfinger

Bonus: Edge of Darkness

Washington turns out for the Mr. Smith premier—they weren't happy.

From Wikipedia: "Alben W. Barkley, a Democrat and the Senate Majority Leader, called the film 'silly and stupid', and said it 'makes the Senate look like a bunch of crooks'."

* And, on Sunday, we'll put up a "Don't Make a Scene" feature from each week's film.