Enter the Dragon (aka 龙争虎斗 Robert Clouse, 1973) The "Citizen Kane of martial arts movies"? I've seen that describing Enter the Dragon and my only reply can be "Good lord, get real"—something difficult to do when you're watching highly stylized choreographed fighting and thinking it authentic. Even the over-the-top spaghetti-western slaps (the entire movie was shot without synchronous sound and was entirely post-dubbed*) that serve as sound effects should clue one in that no one's getting hit, and if they are, they're considered unprofessional when it comes to stunt work. But that's just the action. In terms of story, direction, and general conception, design and ambition, Enter the Dragon is as far afield from Citizen Kane as a supersonic transport is to a crow.

Not to diss crows. I like crows. And it's not a bad thing to like crows. Crows are cool. But don't mistake it for a swan. Or a supersonic transport.

No, Enter the Dragon is a mixed martial arts movie—and when I say "mixed," I'm talking quality. But, I can see where fans on a steady diet of the genre may get the impression it's special. Enter the Dragon is pretty good when you look at the 90% of crap out there that calls itself a "martial arts movie." At least Enter the Dragon has threads of story, a slight attempt at consistent continuity, and even has something as innovative as flash-backs. Maybe that's where the confusion lies. There's some time-travelling cross-cutting going on in Enter the Dragon, and unless you do a serious cross-fading transition with a bell-tree glissando that can be very innovative to people who've been kicked in the head many times.

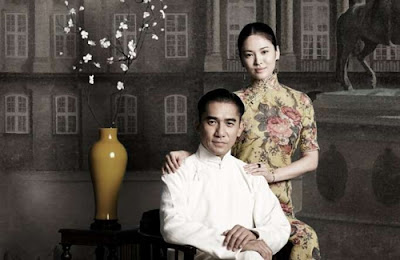

|

| This is what usually communicates "motivation" in a martial arts movie. |

No, it is not a great movie, not by any stretch of charity. It is even a bad copy of what it is trying to emulate (and what appears to be its chief inspiration), a "James Bond" movie. The whole thing is worth watching for one thing and one thing only—Master Bruce Lee. The truth is nobody looks at Enter the Dragon to see John Saxon fight or Jim Kelly act ("Man, you come right out of a comic book!"). Or, if you're somebody who likes looking at endless shots of sampans, Enter the Dragon may be for you, too. But, there are so many of those shots, I think this one would test the patience of sampan junkies, as well.

No, it's all about "the" Bruce and his choreography of the fight scenes, which are designed the way Gene Kelly directed dance sequences...for the recorded image and its limitations of scope and its benefits of the dramatic fluid cut. Lee, after struggling as an actor in Hollywood (TV shows like "The Green Hornet" and "Longstreet," and the movie Marlowe, starring James Garner) moved back to Honk Kong and began working with Golden Harvest Studios as star, choreographer and writer. The output was generating business in the West and Enter the Dragon became the first of the Golden Harvest movies to receive financial support from a major American studio-Warner Brothers.

|

| "Take that, dummy..." |

The story is not much: Lee plays "Lee," a Shaolin martial artist, who is recruited by British Intelligence to participate in a tournament held every three years by Han (Kien Shih), a Hong Kong crime-lord specializing in prostitutes and drug-trafficking. Held on his private island out of the jurisdiction of law enforcement, Han uses the tournament to test recruits for his gang of criminals and assassins. Lee has another motive, though; his sister was murdered by Han's chief enforcer.

|

| When do we get to the GOOD stuff? |

Also participating are two former Army buddies: Roper (Saxon), a ne'er-do-well gambler on the run from The Mob and Williams (Kelly), a political radical of the tamest stripe, who got in trouble with the law. Their motivations are questionable. Their discipline is non-existent (hookers before matches? In The Dirty Dozen, sure, but a martial arts movie?) The two have a side bet about who'll do better, with an eye towards maybe throwing a round to ensure a high pay-out.

|

| "Token White Guy" for American studio "makes time with the ladies." |

Not exactly honorable in the Shaolin way, as Lee is the primary example of a spiritual fighter. But if those two are merely hustlers, then Han, who also studied the Shaolin way, is Lee's opposite in every way, turning to "the dark side" (if you will...) and dishonoring the discipline. In terms of conflict of interest, Lee may be the worst person to spy on the tournament; no matter how disciplined he is, there is going to be some fireworks.

But, not really until the end of the movie. Enter the Dragon has some night-time activity and interim fights to keep interest from flagging. As the movie keeps repeating tournament, tournament, tournament you know you're not going to get to the really good stuff until we get to the point of the movie, where all the stars are on set and there are tons of extras and the director simply sets up the camera and records the prepared matches.** At that point, film aesthetics are thrown away and the only consideration is "keep them in shot and in focus" and cinema is just a window.

|

| Geez...he moved fast. |

|

| It's not the kick that's amazing...look at the dance after |

This is an interesting yin-yang: the film-making is the least interesting where the action is the most intense. It practically begs for what happens next—the requisite breakdown of the tournament into a free-for-all, in which all assembled fight anybody within their orbit of their legs, the tensions of the match descending into chaos. All discipline and all loyalty is lost.

|

| Tournament melee—everything breaks down |

That chaos is the signal for Han to see that his organization is now in a shambles, and he makes his escape into the depths of his lair to be pursued by Lee to exact final revenge on his own own. On his way to his target, he must meet a phalanx of guards and challenges before he can attain his goal. And that confrontation owes a bit of a hat-tip to the cinema of Orson Welles (specifically, Welles' The Lady from Shanghai) as it takes place in a room walled with mirrors.

If there was an doubt about the duality of Lee and Han, two opposite reflections of the Shaolin way, the mirrors make it explicit. It is here that the two have their final showdown, bringing the film to its conclusion, which ends with a rather lame, and not entirely, deserving freeze-frame.

No, it's not Citizen Kane. It lacks the sophistication, or even a hint of the breadth of characterization that that movie offers. Even technically, thirty years on, it has none of the photo-chemical wizardry or the inventiveness to use it that the earlier film has. The only advantage is color and Kane looks far richer in black and white than ETD does in its wide-screen Technicolor.

"The Citizen Kane of martial arts movies?" Not in the least. It's not even a fair match. For all the flailing and fancy footwork of ETD, to compare it to Welles' film is mere hyperbole, even sophistry. There is not even a point of comparison between the two. The argument is merely a weak use of the earlier film to show the form at its peak, as a pinnacle...and even that is questionable these days.

Where the two can be compared is merely a sad one—the loss of potential. After Kane, Welles was never again given the unfettered access of "the world's biggest train-set." And Enter the Dragon was the last completed film of its multi-hyphenate star, who seemed to be ready to move beyond the form that he had just recently conquered, having made in-roads to the path that had been previously denied him. Who knows what he might have accomplished?

|

| The look of a man who can take on anybody in the room. |

Enter the Dragon was Lee's biggest success in the movies, but he did not live long enough to see it. Lee Jun-fan, "Bruce" Lee, died six days before the film's premiere at the age of 32.

|

| Lee's statue on the Avenue of the Stars in Hong Kong. |

* More a matter of convenience than a sign of "cheapness"—this was a multi-national production with various languages being spoken by cast and crew, and as it was intended for multiple markets with multiple languages, it's a matter of practicality to do the many necessary sound versions in post-production.

** Just once in these movies, I'd like them to have one of these "tournament" scenarios and everything gets wrapped up before it can be held—as the organizer is lead away, he weeps "But I bought all these flags!"

The Crouching Tiger in Winter

The Crouching Tiger in Winter

.jpg)