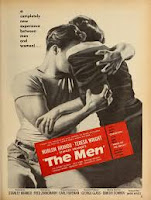

The Men (Fred Zinnemann, 1950)

In all Wars, since the beginning of History, there have been men who

fought twice. The first time they battled with club, sword or machine

gun. The second time they had none of these weapons. Yet this by far,

was the greatest battle. It was fought with abiding faith and raw

courage and in the end, Victory was achieved. This is the story of such a

group of men. To them this film is dedicated.

Soon after director Fred Zinnemann's contract with M-G-M was up—he was stuck directing things like My Brother Talks to Horses but ended his time there with a prestigious low-budget film, The Search—he began working independently for producer Stanley Kramer, a collaboration that culminated in the classic film High Noon. Two years before that western, Kramer, Zinnemann, and High Noon scenarist Carl Foreman made another socially-conscious film about the problems dealt with by injured war veterans who'd lost the use of their legs due to combat wounds. That film, The Men, is largely set in the Birmingham Veterans Administration Hospital, where Foreman and and the film's star did their research for it, and employed many of the patients there as extras and for speaking parts.

That the star is Marlon Brando—in his film debut—makes the film notable, and a touchstone of sorts in terms of film and screen acting. Although Montgomery Clift—also, like Brando, a student of the "Actor's Studio"—had already brought that less theatrical approach to the screen in The Search and the yet-to-be released Red River, it was Brando who had lit the fire on stage in "A Streetcar Named Desire", making his brutish Stanley Kowalski something of a force of disreputable nature and creating a sensation in theatrical circles.

But, "theatrical circles" ain't "Mom and Pop Ticket-Buyer of Everytown U.S.A." And The Men was a fortuitous way for the unconventional actor to make his debut. Brando's portrayal of the embittered paraplegic soldier Ken Wilocek came with its own explanation for why the character would be not-traditionally sympathetic and Brando could avoid any exaggerated sentimentality playing the role.

But, Brando is a stark contrast to the more theatrical performances of Teresa Wright, Everett Sloane, Jack Webb (that's just "the facts") and Richard Erdman. (look real carefully and you'll even see "Star Trek"'s DeForest Kelley playing, naturally, a doctor*). It's unconventional, at least in Hollywood terms of 1950. Check out the review of his performance from Variety of that era: "Brando fails to deliver with the necessary sensitivity and inner warmth which would transform an adequate portrayal into an expert one. Slight speech impediment which sharply enhanced his Streetcar role jars here. His supposed college graduate depiction is consequently not completely convincing."

Ouch. But, then, Variety is a company-town rag which serves as "rah-rah" material for the status quo; it's never been one for spotting innovation.

Maybe it's because I'm used to the Brando eccentricities and (for the most part) appreciate them, but I found his portrayal—"speech impediment" or not—the least affected of the major performances—and I'm a big fan of Wright (Shadow of a Doubt), Sloane (Citizen Kane), and, yes, even Webb (Dun-da-dun-dun). But, Brando feels real. Everybody else comes out and tells you how they feel and why; when Brando's Wilocek finally gets around to saying what he means (which happens rarely) you've already seen it in his face. And when he reacts to something, it's a bit like an explosion—it's fast and unexpected. His Wilocek takes knock after knock, tries and then wallows in self-pity. The cures that Sloane's doctor recommends—exercise, recreation—don't work for him. And the other patients' means of coping, be it drinking or gambling, or intellectualism or exercise are merely distractions from the obvious—they have lost their mobility, and to a large extent, their freedom. Wasn't freedom what they were told they were fighting for?A piece of narration at the beginning is too blunt about it: "I was afraid I was going to die. Now I'm afraid I'm going to live." When he went to war, he was engaged to Wright's Ellen. But he comes back and he has no future—he can't walk her down the aisle and there's a question of whether he (or rather "they") can have kids (the film circles around that question during a hospital Q and A, no doubt due to Hays Code regulations). But, his injury has not only blown through his spinal chord but also his expectations of a "normal" life. He withdraws and, in a case of self-fulfilling prophesy, he rejects her, insisting that she stay away from the hospital, as he no longer is the man she fell in love with.

Sloane's doctor is a big believer in physical therapy as well as a tough-love version of psychotherapy. Initially hesitant to allow Ellen to visit, he relents and Wilocek, while at first reluctant to allow himself to hope, begins to soften.

It sounds very "pat", like the path of a "very special" and "truly inspirational" story-line, but Kramer, Foreman and Brando don't allow it to go smoothly, with added complications and frailties among even the most optimistic and noble of the characters. It's tough on audiences, and Brando's insistence towards playing the part without inviting audience pity makes it a bit more sophisticated...and even a little rebellious from the "socially-conscious" norm. But, it's worth watching...if only to see a moment when Hollywood standards began to shift...and change forever.

Brando clowning on-set.

I remember seeing this years ago... I think it's worth a revisit.

ReplyDelete