Sure, there are a couple of "major" releases in this year's crop of Registry inductees—Amadeus, Platoon and Sleeping Beauty. Maybe Coal-Miner's Daughter. The outlier is Clerks, which got the most write-in votes.

But, if there's a trend in this year's films, it's that they're examples of folks just getting tired of not seeing people like them up on the screen and deciding to be the people to put themselves up there.

There are a couple of technological film advancements—Sleeping Beauty and Becky Sharp—but mostly the films are about what films (and film-makers) do best—giving voices to the voiceless, and making their stories heard.

The Library's comments are the smaller, Times type font. My comments follow in bright white Verdana.

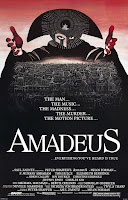

Amadeus (Milos Forman, 1984) Milos Forman directed this deeply absorbing, visually sumptuous film based on the lives and rivalry of two great classical composers — the brash, youthful Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the good, if not truly exceptional, Antonio Salieri. Based upon Peter Shaffer’s highly successful play, which Shaffer personally rewrote for the screen, “Amadeus,” though ostensibly about classical music, instead shines as a remarkable examination of the concept of genius (Mozart) as well as the jealous obsession from less-talented rivals (Salieri). In an Oscar-winning performance, F. Murray Abraham skillfully lays bare the tortured emotions (admiration and covetous envy) Salieri feels for Mozart’s work: “This was the music I had never heard...It seemed to me that I was hearing the voice of God. Why would God choose an obscene child to be his instrument?”

The problems I had with Amadeus were entirely based on Shaffer's play and screenplay. Shaffer pushed the extremes of personalities of historical figures to create obviously discernible antagonists and casting others as complete buffoons. That rather huge consideration aside, Czech-born director Milos Forman does an amazing job of keeping the material breezy, fast-moving, and mixing period detail with splashes of contemporary tweaking. It was enough to convince the Motion Picture Academy to award it that year's Best Picture Oscar (and a very deserving Best Actor Oscar to character actor F. Murray Abraham who talked his way into playing the role of Salieri and then hitting it out of the park) and enough of a con-job to attract contemporary younger audiences that it was a movie about a defiant youth, rather than the story of a preternaturally musical genius of such intensity that it still seems astonishing hundreds of years later.

Becky Sharp (Rouben Mamoulian, Lowell Sherman, 1935) Actress Miriam Hopkins had a long and successful movie career, appearing in many classics, including “Trouble in Paradise” and “Design for Living.” However, it is as this film’s titular heroine that she received her only Academy Award best-actress nomination. Based upon Thackeray’s novel “Vanity Fair,” “Becky” is the story of a socially ambitious woman and her destructive climb up the class system. “Becky Sharp” merits historical note as the first feature-length film to utilize the three-strip Technicolor process, which, even today, gives the film a shimmering visual appeal. The lengthy, complicated restoration process of “Becky Sharp” by the UCLA Film and Television Archive marked one of the earliest archival restorations to garner widespread public attention. Partners in this painstaking effort included the National Telefilm Associates Inc., Fondazione Scuola Nazionale di Cinema, Cineteca Nazionale (Rome), British Film Institute, The Film Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, Paramount and YCM Laboratories. More information can be found at https://cinema.ucla.edu/restoration/becky-sharp-restoration.

I remember seeing "the restored" Becky Sharp at the Seattle International Film Festival and being astounded at what was accomplished. Mamoulian's film—and it is Mamoulian's as Sherman started production while ill and died of double pnuemonia four weeks into filming and all of his footage was scrapped—is a riot of color and the images—except for the vintage blocking—could have been made yesterday. The director's "heightened" realism is even more on display in Technicolor, and even if Becky Sharp was not entertaining, its technical innovation would have made it important in film history. If ever there was an argument for film preservation, Becky Sharp is the lead witness.

Before Stonewall starts with a disclaimer: "Unless otherwise stated, the people who appear in this film should not be presumed to be homosexual...or heterosexual." Cut to Ronald Reagan and George Murphy. Before Stonewall doesn't troll into snarky territory very often, and for the majority of its 90 minute running time bears witness—for upcoming astonished future historians—of the era when the LGBTQ community was stigmatized, harassed, and closeted out of eye-sight, before the proud decided they didn't want to take the abuse anymore, and stood up to the intimidation. The interviews couldn't be more personal and clear-eyed, with few histrionics but simple dignity.

Body and Soul (Oscar Micheaux, 1925) One of the truly unique pioneers of cinema, African-American producer/director/writer/distributor Oscar Micheaux somehow managed to get nearly 40 films made and seen despite facing racism, lack of funding, the capricious whims of local film censors and the independent nature of his work. Most of Micheaux’s films are lost to time or available only in incomplete versions, with the only extant copies of some having been located in foreign archives. Nevertheless, what remains shows a fearless director with an original, daring and creative vision. Film historian Jacqueline Stewart says Micheaux’s films, though sometimes unpolished and rough in terms of acting, pacing and editing, brought relevant issues to the black community including “the politics of skin color within the black community, gender differences, class differences, regional differences especially during this period of the Great Migration.” For “Body and Soul,” renaissance man Paul Robeson, who had gained some fame on the stage, makes his film debut displaying a blazing screen presence in dual roles as a charismatic escaped convict masquerading as a preacher and his pious brother. The George Eastman Museum has restored the film from a nitrate print, producing black-and-white-preservation elements and later restoring color tinting using the Desmet method.

Ostensibly, it's a morality tale of two brothers: one (Sylvester) good and one (the Rev. Isaiah T. Jenkins) very, very bad. There are enough surprises given the themes and the times it was made, that even today it's a bit radical. But, it's also a showcase for the legendary Paul Robeson, who plays both brother roles. And the legend holds, as the two characters have nothing in common other than they share the same face. The Rev. Isaiah is a moral-less preacher, who uses the power of the cloth with the sole purpose to exploit it and his flock for his own venal purposes. Written and directed by pioneering black film-maker Oscar Micheaux, it displays in the most basic visual terms possible, Martin Luther King's dream of prizing character over looks.

Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Pierce, 1999) Director Kimberly Peirce made a stunning debut with this searing docudrama based on the infamous 1993 case of a young Nebraska girl who elects to live as a transgender man, but is brutally raped and murdered (along with two other people) in a small Nebraska town. Released a year after the killing of Matthew Shepard, a gay student at the University of Wyoming, the film brought the issue of hate crimes clearly into the American public spotlight. Sometimes compared to Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy,” “Boys” raised issues that are still relevant 20 years later: intolerance, prejudice, the lack of opportunity in small towns, conceptions of self, sexual identity, diversity and cultural, sexual and social mores. New York Times’ critic Janet Maslin lauded the film for not taking the usual plot routes: “Unlike most films about mind-numbing tragedy, this one manages to be full of hope.” Several things helped create that result, particularly the performance of 22-year-old Hilary Swank, who won an Oscar as Brandon.

Swank got the Oscar (deservedly), but everybody in this does a great job of living-in performances, that keeps the film from straying into melodrama but keeping the context of a small-town tragedy. Controversial among the folks who lived it, Boys Don't Cry is a searing look at toxic masculinity, whether it comes from a narcissistic ex-con (Peter Saarsgard) or from a teen girl aspiring to that same power-dynamic in the quest for identity.

Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994) A hilarious, in-your-face, bawdy-yet-provocative look at two sardonic young slackers (Dante and Randal). One toils as a New Jersey convenience store clerk while his alter-ego video store friend works when the mood strikes him. At 23 years old, Kevin Smith made his debut film for $27,000, reportedly financed by selling his comic book collection and using proceeds from when his car was lost in a flood. This sleeper hit helped define an era, grossed over $3 million, achieved prominent cult status among Generations X to Z, and easily garnered the most public votes in this year’s National Film Registry balloting. Critic Roger Ebert described “Clerks” as “utterly authentic” with “the attitude of a gas station attendant who tells you to check your own oil. It's grungy and unkempt, and Dante and Randal look like they have been nourished from birth on beef jerky and Cheetos. They are tired and bored, underpaid and unlucky in love, and their encounters with customers feel like a series of psychological tests.”

Hilarious? Not really. Clever? Absolutely. Smith's first film is the top vote-getter among the public this year. Can Snakes on a Plane be far behind? Clerks is not a great movie, and Kevin Smith is not a great director (the film, though, has had two sequels as well as an animated series, which means it was a good thing his editor convinced him to cut the original ending that had the lead character killed in a robbery)...but his screenplays amuse and have a nice sense of raw humor, some wisdom, and quite a bit of heart. Oh. And Jay and Silent Bob, the C-3PO and R2-D2 of Smith's films. His best film is still Chasing Amy because it's the least frivolous. But it's also the most melancholy, where Smith is at his most effective as a class clown and not a "statement-maker".

Coal Miner’s Daughter (Michael Apted, 1980) The exceptional life of country music legend Loretta Lynn is traced in this classic biopic documenting her unlikely ascent as a child bride from Butcher Hollow, Kentucky, to superstar singer and songwriter. Never shying away from Lynn’s professional and personal struggles, “Coal Miner’s Daughter” helped set the standard for every musical biography that has followed it. Sissy Spacek earned an Academy Award for her deeply heartfelt and true-to-life performance in the lead role. She is matched by her co-stars Tommy Lee Jones as Lynn’s husband “Doo” and Beverly D’Angelo as Lynn’s mentor, the late Patsy Cline.

I always remember a line from Coal Miner's Daughter uttered by The Band's Levon Helm playing Lynn's father, as he tries to convince her not to get married at the age of 14. "Yer my pride, girl. My shinin' pride." I also remember Spacek's Lynn dousing a Tommy Lee Jones mad-on with a seprecating "Oh, Doo, yer as growly as a big ol' ba'ar." In fact, it was the first time I was impressed with a Tommy Lee Jones performance after a decade of seeing him under-perform. Everyone is terrific in the movie, well directed by Michael Apted, with Spacek not really reminding you of Loretta Lynn but playing her so extraordinarily—and doing her own singing—that you don't care. And Beverly D'Angelo is so good as Patsy Cline, you have to remind yourself that Cline actually died in a plane crash. Coal Miner's Daughter has rarely been topped as a country bio-pic, the only one coming close being Walk the Line.

Abadie photographed the grandparents of the people who complain about immigration, immigrating.

Employees' Entrance (Roy del Ruth, 1933) During the bleak era of the Depression, film studios scrambled to find various types of “escapist” fare to take people’s minds off their hard life struggles and get audiences into theaters: musicals, lighthearted comedies and melodramas with big stars. “Employees Entrance,” a superb pre-Production Code film about the machinations in a New York department store, effectively captures real urban tensions during the Depression. Key is Warren Williams’ devastating characterization of the store’s general manager, whose system shows not a trace of the smiling manager. He’s always superb as a charismatic, shyster professional, is obsessed with being successful, callously dismissing longtime, non-productive employees and demanding that his assistants not succumb to women. Warner Bros films of the 1930s are renowned for being fast-paced, quickly made, relatively short features (55-75 minutes) with whip-smart dialogue. “Employees Entrance” remains one of the studio’s best.

One of those Pre-Code films that feels just as pertinent in these #MeToo/"business autocracy" days. The Monroe department store is enjoying good business quarters due to efforts of its manager Kurt Anderson (Warren William), despite what bank investors consider his "overzealous" methods, with a philosophy centered on "There's no room for sympathy or softness - my code is smash or be smashed!" But, success keeps him in charge, as does serial sexual harassment and blackmail. Things get complicated when he seduces a store model (played by Loretta Young) who happens to be in love—then marries—his assistant (Wallace Ford). Audacious and free-wheeling, it's one of the most unintentionally hilarious satires of corporate venality pre-Gordon Gecko.

And it's another chance to watch "The King of Pre-Code" Warren William, who died at 53 and has faded to obscurity, despite being the first actor to play "Perry Mason" and for starring in the second (of three) adaptations of "The Maltese Falcon." William has the talent to say to an employee that threatens to kill him "That's the spirit!" and make it work. Despite being a hissable snake, William is a delight to watch.

The Fog of War (Erroll Morris, 2003) In “The Fog of War,” idiosyncratic documentary filmmaker Errol Morris interrogates one man, Robert Strange McNamara, who served under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson as secretary of defense. Educated and trained as a systems analyst for large organizations, McNamara at age 85 reexamines his fateful role as one of the prime U.S. architects of the Vietnam War. Recounting as well the U.S. incendiary bombing campaign during World War II against 67 Japanese cities that resulted in mass civilian deaths, his role at the Ford Motor Company in implementing safety features to reduce the number of deaths, and the defusion of the Cuban Missile Crisis through an empathetic understanding of the enemy, “The Fog of War” is structured by 11 lessons Morris has drawn from McNamara’s remembrances and ruminations. Historians and reviewers have both praised “The Fog of War,” winner of the 2003 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, for revealing in a riveting manner the moral complexities and unresolved nature of McNamara’s understandings and criticized the film for its selective presentation of the events discussed.

The actual title is The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara. They are:

1. Empathize with your enemy.

2. Rationality will not save us.

3. There's something beyond one's self.

4. Maximize efficiency.

5. Proportionality should be a guideline in war.

6. Get the data.

7. Belief and seeing are both often wrong.

8. Be prepared to reexamine your reasoning.

9. In order to do good, you may have to engage in evil.

10. Never say never.

11. You can't change human nature.

I'd like to think I saved you a couple of hours of your time and maybe some lives in the next war, but I'm sure I'm wrong on the second point.

Gaslight (George Cukor, 1944) Based on the Broadway play and also staged under the title “Angel Street,” MGM’s “Gaslight” is the story of a Victorian woman who is slowly going mad — or is she? Ingrid Bergman won her first Oscar for her spellbinding performance in the lead role while Charles Boyer skates the precarious edge between romantic hero and devious villain. They were ably assisted by Joseph Cotten, Dame May Whitty and, in her film debut, Angela Lansbury as a cockney maid. Expertly directed by George Cukor, the film remains as suspenseful as the day it was made, just as the term “gaslighting” remains firmly within our cultural lexicon.

"You are typically losing things, my dear Paula" says pianist-composer Gregory Anton (Charles Boyer) at one point in Gaslight. What he may be referring to is her mind. Well, it's always in the last place you look. It has been a whirlwind romance that has brought newlywed Paula Alquist (Ingrid Bergman) back to live at 9 Thornton Square, where he mother was killed during a robbery ten years before. Her husband, Anton, is such an unfeeling jerk that, despite her efforts to please, he maintains a stony cold-heartedness. And then, the lights begin to dim for no apparent reason, she begins to hear strange noises, becomes forgetful and loses things. Something's afoot, and it's only the objective observations of Scotland Yard Constable Brian Cameron (Joseph Cotten)—and the couple's "Kravitzing" neighbor, Miss Thwaites (Dame May Whitty)—who care enough to interfere before Paula is tortured into a nervous breakdown. Cukor knew from male toxicity and he allows some revengeful torture before everything gets resolved.

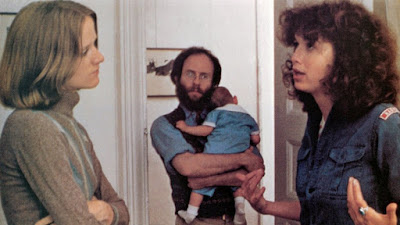

Girlfriends (Claudia Weill, 1978) On its release, Stanley Kubrick described Claudia Weill’s “Girlfriends” as “one of the most interesting American films he had seen in a long time.” A fiercely independent, single New York photographer (in a marvelous performance by Melanie Mayron) aspires beyond doing bar mitzvahs and weddings and struggles with relationships and city life after her best friend and roommate moves out to get married. Weill critiques the historically prevalent notions of women, marriage and motherhood, and the difficulties in pursuing an alternative lifestyle. The film uses deft observation of minor intimate vignettes (one has Mayron making a boyfriend pass the “mumps” test) to capture the life of a single woman trying to make a career during the Gloria Steinem-esque era of sexual freedom and the responsibilities and dangers that entails.

One might look for larger themes in Girlfriends, and, certainly, it paints a picture of single-life in New York in the 1970's for working women, but more for this particular woman. Susie Weinblatt (Mayron) isn't exactly sure what she wants other than to be wanted—success as a photographer, sure, a stable relationship, sure. But, other than that she just knows what she doesn't want—because she has clear examples of that everywhere she turns. And just when she thinks she has a handle on happiness, something disrupts her, whether it is friends moving apart, or friends ignored, a loving relationship with men her age (like that played by Christopher Guest) or an older married rabbi who treats her decently (Eli Wallach). Lesbianism is out—way out for her, but she slowly, through the film, begins to see herself the way others see her and that it's not "a" relationship, but "relationships" that fulfill a life. It's no wonder Kubrick liked it—it plays a bit like his Eyes Wide Shut as a cautionary tale for going with one's gut instead of one's reason.

I Am Somebody (Madeline Anderson, 1970) Madeline Anderson’s documentary brings viewers to the front lines of the civil rights movement during the 1969 Charleston hospital workers’ strike, when black female workers marched for fair pay and union recognition. Anderson personally participated in the strike, along with such notable figures as Coretta Scott King, Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young, all affiliated with Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Anderson’s film shows the courage and resiliency of the strikers and the support they received from the local black community. It is an essential filmed record of this important moment in the history of civil and women’s rights. The film is also notable as arguably the first documentary on civil rights directed by a woman of color, solidifying its place in American film history.

The story of the 100 day strike by Hospital Workers Union Local 1199b in Charleston, South Carolina for a higher wage—forget the terms "decent wage" or "living wage"—which went on for so long without being resolved, probably due to race and sexism, that the NAACP lent their support and even the recently widowed Coretta Scott King came out to March. The resultant publicity—and disruptions to hospitals—ultimately forced a capitulation.

The Last Waltz (Martin Scorsese, 1978)

Martin Scorsese’s documentary is a homage to the epic 1976 Thanksgiving farewell concert by The Band at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco. Performances include Eric Clapton, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Neil Diamond, Bob Dylan, Van Morrison, the Staple Singers, Emmylou Harris and others. As Robertson recounts: “We had to play 21 songs with other artists, going from Muddy Waters to Joni Mitchell. …We played this five-hour concert and we didn't make a mistake." Some believe this concert marked the beginning of the end of the classic rock era.

The Last Ride of The Band—they were breaking up over personal issues and a certain amount of band animosity—led to a concert that was less about their legacy than about padding "the bill." Originally, Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan were to be the only ones playing with them, as their history with the band-members was obvious—they were session-men. But, somehow, the list ballooned as to be nearly ridiculous—Neil Diamond was there and only because Robbie Robertson had produced an album for him.

My Name Is Oona (Gunvor Nelson, 1969) Born in Sweden in 1931, Gunvor Nelson in 1953 moved to the U.S. where she spent the middle years of her life before moving back to Sweden in the early 1990s. She taught at the San Francisco Art Institute from 1970-92, influencing a generation of new filmmakers. She carved out a distinctive niche in underground avant-garde American film during the 1960s and ‘70s though Nelson strongly prefers the term “personal cinema.” Much of her work during this period concerns perceptions of feminine beauty. In “My Name is Oona,” Nelson paints an expressive portrait of her 9-year-old daughter’s flowing, dreamlike interactions with the forces of nature via experimental techniques such as the superimposition of fleeting images, dynamic editing and slow-motion cinematography. The sublime effect created in “Oona” provides a lyrical, 10-minute look into the non-linear, vivid, sometimes wild or scary world of childhood memory and imagination, as well as a child’s halting steps toward self-realization.

A New Leaf (Elaine May, 1971) Elaine May became the first woman to write, direct and star in a major American studio feature with “A New Leaf.” Critics loved the comedic confrontations of the film’s two cartoon-like eccentrics, played with uncommon understatement by May, as a socially inept but wealthy botanist heiress, and Walter Matthau as a conniving and murderous misanthrope in pursuit of her fortune. Their encounters reminded reviewers of the droll sensibility that made the legendary Mike Nichols and Elaine May satiric sketches created years earlier for nightclubs and records so appealing. For “A New Leaf,” May drew on classic Hollywood comedy traditions of Depression-era screwball comedy and slapstick. Despite a failed lawsuit by May to have her name removed from the credits because the released version did not match her vision of the film, audiences flocked to it and the film has become a cult classic. May’s conflicts with Hollywood studios continued, eventually ending her career as a feature film director in 1987. After recently winning a 2019 Tony Award for best actress in a play, she has been slated to direct a new feature film at age 87.

The original rough cut of Elaine May's directorial debut ran 180 minutes and was deemed too long by Paramount Pictures and its Production head, the late Robert Evans. Evans cut it himself, removing major subplots and getting it down to 102 minutes—which is the version I saw in 1971. I wasn't that impressed with it when I saw it, finding it black and subtle with Walter Matthau perhaps being too broad for it—I DO remember the oft-repeated line "...carbon on the valves..." for anything amiss with transportation be they cars or horses. Given Paramount's history of making very good movies NOT very good by editing, I think I would enjoy May's version—if it could ever be found—far superior to what Paramount released. She was keeping the original under her bed at the time. Has anybody looked there?

Old Yeller (Robert Stevenson, 1957) Stories of boys and their dogs have long been fodder for films and books, but none has ever resonated more strongly with the public than this 1957 adaptation of the Fred Gipson novel. Produced by Disney, which knew how to touch the hearts of moviegoers with both laughter and tears, the beloved film was directed by Robert Stevenson and stars Fess Parker, Dorothy McGuire and Tommy Kirk. Few movie endings have ever proved as emotionally affecting as the conclusion of “Old Yeller.”

"Best doggone dog in the West" goes the song. "Crazier than a bull-bat" is how 15 year old Travis Coates (Tommy Kirk) describes him. The yellow lab stray has caused too much trouble for Travis not to want to shoot it as much as he can look at it. And Dad Jim (Fess Parker) being away until the Fall gathering up some cattle and all. But, the dog bonds with little Arliss (Kevin Corcoran), who'll bring in any stray varmint he can fit in his overall pockets. But, the thieving egg-suckin' lab' earns his keep when he saves Arliss from a Mama bear trying to protect her cub from being man-handled by the boy.

Disney knew how to stage good animal action, but the actors have to be praised for keeping things from getting too arch or corny. The kid-actors are good. But, extra praise should go to Dorothy McGuire and to Chuck Connors for playing along.

The Phenix City Story (Phil Carlson, 1955) Film noir comes to Alabama in this ripped-from-the-headlines tale in a film based on notorious real-life 1954 events, Albert Patterson is an attorney trying to clean up his mob-controlled town — Phenix City, aka “Sin City, U.S.A.” — and is killed while running for state attorney general. Tight, tense and graphic for all 100 of its minutes, the film has been lauded for being both stylish and for its semi-documentary style.

Noted B-movie director Phil Carlson crafted this low-budget, violent shocker, using innovative camera work, which unnerved audiences not accustomed to seeing so much on-screen violence. In real life, the infamous murder quickly led the state to break up the crime syndicate, and Patterson’s son eventually became state attorney general and the governor of Alabama. The 87-minute film was also released in a longer version, which included a 13-minute newsreel.

Holy crap! This is one of those film-noir's where nobody talks, they either sneer, yell, threaten or scream, and Phil Karlson—not the most subtle artist—throws in as much blood, punching, and affronts to common decency as one could imagine for a movie made in 1955. One would be shocked...if it wasn't based on a true story! The town of Phenix City, Alabama is so run by gamblers, bootleggers, and thugs, that they control the elections, the police and have a hand in every legitimate interest in town. Just a body's throw from Ft. Mead, it attracts all sorts of leave-taking as long as there isn't any trouble beyond its infamous 14th Street. Things come to a head when a reformist wins the Democratic primary for State Attorney General and is promptly gunned down that night. The governor has to call in the National Guard, and the ring-leaders arrested to stand trial—and they were still standing trial in real life when the movie was filmed. John McIntire plays Albert Patterson who after years of looking the other way starts to see the violence escalate when his son John (played by Richard Kiley) returns from Korea with his family to find he's returned to another war-zone. Once kids start getting killed and whole families blown up in their homes, well, the old "Evil is allowed to thrive when good men do nothing" is trotted out. Edward Andrews plays the "Root of All Evil"--just to keep things simple.

Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986) Eschewing the rah-rah fiction of many Hollywood war movies, always-fearless director Oliver Stone created “Platoon” based upon his own experiences in Vietnam. Stone intended the film to show the malignancy of war and to serve as an important counterpoint to earlier heroic depictions of the Vietnam conflict, most notably John Wayne’s “The Green Berets.” Actor Charlie Sheen stands in for the real-life Stone, ably assisted by a cast including Tom Berenger and Willem Dafoe. The memorable soundtrack features visceral, haunting use of Samuel Barber’s elegiac “Adagio for Strings.”

One shouldn't discount Georges Delerue's original score, either, Library...

The first of Oliver Stone's "Vietnam Trilogy" (the others are Born on the Fourth of July and Heaven and Earth), Platoon beat out Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket by a year, thus capturing the speed-prize for more straight-forward adaptations for the conflict (as opposed to say "Vietnam as a metaphor" movies). It's intense in the battle scenes, Stone's film based those on his impressions during his tour in Vietnam, and is the first of Stone's contemplation of (what Kubrick dismissed as "the duality of man, the Jungian thing" in FMJ) conscience. By setting up a protagonist (played by Charlie Sheen) torn between the philosophies of two diametrically opposed father figures (Tom Berenger and Willem DaFoe) in finding his true path. In a way, it's also the first stroke in Stone's career-long obsession with the Military-Industrial Complex, which despite different genres and subject matters, he eventually circles back to.

Purple Rain (Albert Magnoli, 1984) By 1984, Prince was already being hailed by critics and fans as one of the greatest musical geniuses of his generation. This post-modern musical secured his place as a movie star and entertainment legend. Largely autobiographical, “Purple Rain” showcased the late, great showman as a young Minneapolis musician struggling to bring his revolutionary brand of provocative funk rock to the masses. The film’s soundtrack includes such decade-defining tracks as “When Doves Cry” and the title song. The film’s multi-platinum soundtrack previously was named to the Library of Congress National Recording Registry.

MTV (they used to play music videos?) was in full swing when this film was written and produced, but until Michael Jackson's "Thriller" was released, they didn't feature black artists...at all. Prince had been doing well with albums, but there was some reluctance to expand his marketability because his funk-swagger had issues about content. The artist (before being "The Artist...") had been wanting to do a film project and after a couple false starts, Magnoli was brought in to write and direct. Studios love films with marketable "song" soundtrack albums (think A Hard Days' Night's success), so Warner Brothers green-lit the project—but suggested John Travolta play The Kid...really).

The result was that during a week in 1984, Prince had the #1 album, single, and film in the U.S. The film won an Oscar for song score (the last one given) and two Grammy's. The film is an atmospheric MTV type film, long on visuals, but short on plot and follow the "youth movie theme: musical division" of struggling artist has trouble at home as well as career, but a catharsis brings him his first taste of success. (See also 8 Mile). But, it launched Prince into superstar status, mature content be damned.

Real Women Have Curves (Patricia Cardoso, 2002) Before gaining stardom a few years later in the TV series “Ugly Betty,” 18-year-old America Ferrera made her film debut and gained notice from critics in this coming-of-age tale as an impossible-to-resist Latina teen trying to fulfill her dreams while navigating the transition to adulthood. Charming and funny, the film (thanks to director Patricia Cardoso) avoids heavy-handedness by taking a refreshingly subtle look at themes including mother-daughter relationships, the immigrant experience, the perception of feminine beauty and body standards.

Think Prince is mis-understood? Try Ana Garcia (America Ferrera), working in her family's garment factory, just graduated from high school, overweight, and constantly under the critical thumb of her mother and sister. Living East L.A., the prospects aren't many, and she's resigned for this to be her future. But a school counselor thinks he can get her into Columbia U (in NY), so she works by day, studies at night and rolls the dice, knowing that the biggest hurdle will be the family who loves her and wants the best for her...just don't get too full of yourself. And don't leave home.

It's been years since seeing this one—on cable, no less—but the impression still is warm and appreciative. It's a funny poignant film about the irony of expectations and how they conflict, depending on whose expectations they are.

She’s Gotta Have It (Spike Lee, 1986) The distinct voice and cinematic talent of Spike Lee first became evident thanks to this indie classic. “She’s Gotta Have It” tells the story of a confident, single black woman (in itself something of a breakthrough) pursued by three different African-American men —and who isn’t sure she wants any of them. More than 30 years later, this landmark work remains as vital, vibrant, charming and streetwise as it was at first release, a harbinger of Lee’s enduring and visionary career as filmmaker. Lee also appears in the film as the memorable Mars.

Spike Lee's first film outta NYU got a lot of people's attention. It was a distinctive director's "voice" and style, it starred a woman, dealt with women's issues and dealt with women's issues about sex. Plus, it had the audacity to have the woman be in control of her body and have HER be the one who's in charge...and if the men in her life don't like it (well, then, they're not in her life).

Lee's style was fresh, confident, in your face, and not afraid to play with the film-making process, broken fourth walls or any other rules associated with film-making. Walls just come tumbling down. At one point, he stops his black-and-white film for a color musical sequence, where the song serves as dialog. It's provocative, playful, scathingly pointed, and Lee immediately started doing work for commercials...like Nike...to bank-roll his next films.

|

| "This was the deal..." |

Sleeping Beauty (Clyde Geronimi, 1959) The story of the sleeping princess Aurora, awakened by a kiss, already was widely known to theater audiences. But Disney transformed this timeless fable from the original Charles Perrault fairy tale (“The Sleeping Beauty of the Wood”) and The Brothers Grimm (“Little Briar-Rose”) by tweaking plot elements and characters (such as the number and role of the fairies), as well as with the film’s magnificent score. Along with its vivid images and charming details, the film introduced movie audiences to one of Disney’s most enduring villainesses — Maleficent (voiced in the 1959 film by Eleanor Audley). “Beauty” was the last of classic animated fairy-tale adaptations produced by Walt Disney, whose influence suffuses the film.

The Disney Studio worked on its "Sleeping Beauty" adaptation for most of the 1950's starting with story conferences in 1951 and releasing it in 1959. In its purest form, the film was released in SuperTechnirama 70mm and with six track stereo sound and was the last of Disney's "fairy tale" animations until The Little Mermaid made a splash in 1989. Although the story is about Princess Aurora, "The Sleeping Beauty" she is only in the film for 19 minutes, the story concentrating on her trio of fairy helpers and on the villainous Maleficent (who would feature in the "Wicked" themed live action remakes with Angelina Jolie), probably to keep the film from seeming too much like Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarves—a directive that Disney kept hammering away at during the film's creation. One of the animators who worked on the film was Chuck Jones, when his Warner Brothers cartoon home was briefly disbanded in the 1950's.

Zoot Suit (Luis Valdez, 1981) Innovative in its presentation, which is largely a filmed stage play, director Luis Valdez’s “Zoot Suit” relates the real-life story of Los Angeles’ 1942 “Sleepy Lagoon Murder” and the racially charged “Zoot Suit Riots” that occurred in its wake. A highly stylized musical, the film nevertheless retains the power of its source material. Daniel Valdez, Edward James Olmos, Charles Aidman and Tyne Daly make up the cast while the music is supplied by Daniel Valdez and Lalo Guerrero, considered the father of Chicano music, among others.

Budget constraints probably forced the unique way Zoot Suit is put together. It would have been tough to recreate 1940's LA anywhere except in the theater where the original production was taking place. It allowed for greater stylization and a unique record of that actual stage presentation itself, without having to deal with scene-changes, intermissions and the like, and being able to jazz it up and give it up a bit more life with dramatic camera angles.

So, it's not a "filmed stage play" with a standard three-camera technique. It's a stage play filmed where the sky's the limit and even the stage-lights don't matter, combining the proscenium arch and the verve of an M-G-M presentation. Really quite unique.

No comments:

Post a Comment