That last one is particularly frustrating to conspiracy-theorists because they already know what the "motivation" is: it's a saliva-sputtering, eye-bugged response of "Evil! Pure and simple from the eighth dimension!!"*

(Yeah, well, except for the "eighth dimension" part, but the rest of it is completely accurate).

If the criminal master-plan of Mabuse isn't epic, the movie containing it certainly is; Dr. Mabuse, der Speiler runs 4½ hours in length in two parts—"The Great Gambler: A Picture of Our Times" and "Inferno: a Game for the People of our Age". In them, a criminal mastermind, plays havoc among the rich and powerful in Berlin, manipulating the strata of society for his own ends. Although notably intuitive and machiavellian, Mabuse knows himself so little (maybe because he loses himself so much in his talent for disguise) that he is vulnerable to be noticed by the common behaviors that connect his many persona's; make-up is only skin-deep but hubris goes right to the soul.

The film starts (ala the James Bond series) with an action sequence where a much-anticipated business contract is stolen and hidden away via an elaborately circuitous route that transfers the goods from one conveyance to another to throw off any pursuers, of which there are plenty. The final transfer takes scheduling and exquisite timing, indicating careful yet daring planning. The stolen contract is enough to de-stabilize the German stock-market, all planned to make Mabuse—who manipulated certain stocks and arranged the contract heist—a very rich man.

Cue the villain: we see a hand of photos fanned like playing cards, but all the images belong to one—Mabuse (Rudolf Kleine-Rugge), doctor of psychology, master of disguise and the scourge of the Berlin underworld to all law agencies, who is working in his laboratory extracting venom from a cobra for some nefarious future scheme, perhaps...(or maybe, it's just something that he likes to do). He proffers the drained snake to one of his barely competent hench-men Pesch (another, Spoem, is a drug addict, but there are many others) and, having already made a fortune, prepares to make his next one. This one Mabuse chooses to perform personally, rather than rely on his network of "useful idiots."

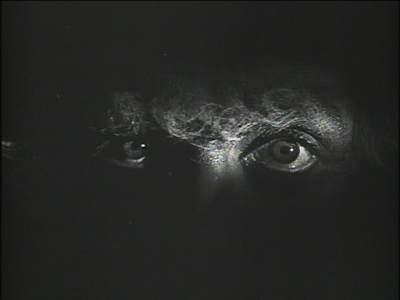

Choosing another disguise, he goes to a Gentleman's Club for a bit of gambling. He selects as his victim the rich Berlin scion Edgar Hull (Paul Richter), who, though he's no slouch at the gambling table, begins to play ill-advisedly. Mabuse is also, among his many talents, a hypnotist able to control the mind of any poor mortal who dares look into his eyes. He is able to easily control the play of the young Hull, who loses a fortune to the disguised Mabuse. Maybe it's ego that allows Mabuse to come out of his lair to risk exposure by personally taking a hand, but for whatever reason, it is a lucky break for the authorities.

|

| Don't look. No. Really! Don't...oh, too late. |

Mabuse learns the identity of his pursuer and that he is working with Hull to discover who he is. He decides to move against the two men, using his moll, the dancer Cara Carozza (Aud Egede-Nissen) to seduce Hull; she lures Hull to an illegal casino, expecting van Wenk to follow them, but the imperturbable lawmen orders a raid on the premises, instead. Mabuse is only partially successful—Hull is killed, but van Wenk captures Carozza and has her jailed and interrogated, but the woman, in thrall with Mabuse, is no help. Even recruiting his friend, the Countess Told (Gertrude Welker) and putting her in the same cell as Carozza, does not encourage any betrayal on the woman's part, despite there being no response from Mabuse and no attempts to try and spring her free. By the end of the first part of the film, Carozza is in custody and Mabuse sets his sights on destroying the Countess Told, driving her husband the Count insane and destroying van Welk utterly and forever. The chess-pieces are all in place; it's merely up to the chess-masters to move them to their final ends.

By this time, Mabuse has taken on a guise far more powerful than just a manipulator of minds; he is "The Great Unknown," master of his own fate and the fate of so many more. He becomes the personification of evil, a literal spell-binder, able to manipulate the suggestible and gullible to whatever end he so desires. A person of indomitable will (and ego) using the weak to carry out his handiwork, while he merely sits back and pulls the strings of his puppets, calculating advantages, anticipating set-backs, fine-tuning the mayhem, plotting...forever plotting. His only down-side is his own lack of self-awareness, his own hubris; he can't resist inserting himself into the machinery, putting himself at risk of exposure. Perhaps he thinks he is just too brilliant to be caught, and if he's discovered, then what of it? He will merely eliminate the discoverer.

That's the template: pernicious foe and implacable adversary. The bad guy creates the situation and a good guy must solve and resolve it; it's a bit backwards from the usual scenario as the bad guy is the focus and must be defeated—the hero is something of a cipher, far less interesting than the villain of the piece, but who is just very, very competent and tenacious. All of this is set up in the first part of the film, and Lang merely brings in additional victims and supporting characters to add more strength to the web of intrigue. They are mere complications, not even making things more difficult for either adversary, just adding to the mayhem...and the body-count.

|

| Don't look. Really? I have to tell you this again?. I just can't convince you to NOT look, can I? |

The film was made in 1922, so it presaged the rise of Hitler by seven years, but Mabuse's power to manipulate has been influenced by many charismatic figures (Rasputin, for example had died merely six years before) and, in the years since, there has been no shortage of Mabusian-type stand-in's at the center of conspiracy theories that try to explain events in a way that defies the concepts of randomness or coincidence. His influence extends even to this day, where fanciful bits of business are twined together on the walls of the deluded, looking so hard for connections that sometimes they miss the obvious. Conspiracy theories are the bread and circuses for those whose minds aren't more worthwhile engaged. And popular entertainments such as this and other "Napoleon-of-crime-stories" only seem to encourage such pursuits and flights of fancy. I always joke when things get hysterical in movies that those involve should "just get a good night's sleep." But, how can one sleep with so much rampant corruption occurring?

|

| Mabuse is confronted, ala Shakespeare, by his ghosts...and his deeds. |

* A line from Buckaroo Banzai: Across the Eighth Dimension.

No comments:

Post a Comment