or

What Makes Bobby Run Away?

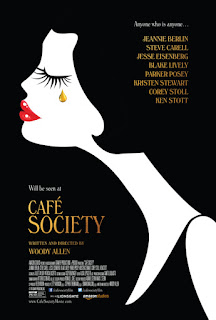

I have not seen American Ultra—the second pairing of Jesse Eisenberg and Kristen Stewart (after their 2008 Adventureland), but I'll hazard a guess it isn't anywhere nearly as impressive as the work from either of them as Café Society is. Woody Allen's new film, set in the 1930's features the two as on-again, off-again lovers in Hollywood with big dreams and big hearts, all the better to crush them with.

This is Allen's version of "The Great Gatsby," with more domestic judaism and less dream-swept into absurdity, and thus, it is more relatable for that. The setting is more Hollywood than West Egg and so the surface glamour seems thinner and less substantial and more easily dismissed than the Ivy League prestige that is taken SO seriously. Legacy, ya know.

Bobby Dorfman (Eisenberg) moves to the West Coast from the Bronx without any prospects. His mother Rose (Jeanne Berlin) calls her brother Phil Stern (Steve Carell), an established Hollywood agent, to give Bobby a leg up and maybe find him some work. He's family, after all. Stern is a big wheeler-dealer and a name-dropper of some magnitude, and, if anything, he'd just as soon forget he has any family on the East Coast, but after a week of prevaricating, he deigns to see Bobby and likes what he sees—an eager, puppy-eyed, but not naive intellectual who obviously looks up to his Uncle. There's no job in the mail-room, but maybe he can do some odd-jobs for Stern, he'll let his assistant Vonnie (Stewart) show him around town, and, hey, there's a party Phil's throwing where Bobby can meet a lot of IMPORTANT people. Important people.

Bobby does well. He mingles professionally, and meets a nice couple Steve and Rad Taylor (Paul Schneider and Parker Posey), who take a liking to Bobby. And his city-tours with Vonnie are his favorite part, riding around town looking at the extravagant homes, taking in shows at the bijou (the Stanwyck The Woman in Red is showing so it must be 1935), talking, getting familiar, both with the city and with Vonnie, with whom he starts to fall in love. For her part, Vonnie likes him but she has a boyfriend-journalist she tells Bobby about and they remain friends and confidantes.

Back in the Bronx, the Dorfman's are excited about Bobby's prospects, but the family is in turmoil with the youngest being so far from home—Rose worries but father Marty (Ken Stott) is unconcerned, sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick) and her communist husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken) are fighting with their neighbor, and brother Ben (Corey Stoll) has moved up from being a petty thief to a shady businessman with gangsterish tactics.

Back in Hollywood, the boyfriend falls out of the picture and Bobby and Vonnie become lovers. Bobby is already thinking about moving back to the Bronx with her as his wife, by Vonnie is slightly ambivalent about the prospect. Before long, the absent boyfriend comes back and Vonnie chooses him over Bobby, and he is left bereft-especially considering who that boyfriend is.

Anyone who's seen a Woody Allen in the past might be able to predict who the boyfriend is (even if IMDB didn't "spill the beans" in their "spoiler free" synopsis). The Woody-verse is pretty limited, even when doing multiple stories in a single movie (like To Rome With Love), so the acorns don't fall too far from The Woodman. There is no way Bobby can live with the humiliation, so he slinks back to the Bronx, back to his family. Brother Ben takes him at the juice joint he's running (the former business partner having become the cornerstone of some highway in the outskirts).

He makes a "go" of it, the nightclub becoming a New York hot-spot attracting the rich and powerful and under indictment. It's where Bobby meets his socialite shiksa wife (Blake Lively), also named Veronica, and life moves on successfully.But, life has a way of cycling back on you, and Vonnie shows up at the nightclub like Ilsa Lund in Casablanca, and Bobby goes from the BMOC to also-ran in the blink of an entrance. He's happy and successful, but his disappointing past shows up to haunt him. And despite his success he still has to right the wrong. How messed up is that?

It's "Gatsby," yes, with a little bit of Billy Wilder thrown in to the mix, because Allen can't help but make things a little bit more complex than Fitzgerald was capable of—Allen is just as much a romantic, but can't quite get past the point being a realist about it, and looking past the glamour. It's only natural—that Hollywood angle again. Allen has always been deeply cynical about the veneer of Hollywood—maybe it's the constant sun (one of his early jokes was "I'm red-haired and fair-skinned; I don't tan, I stroke!"), the appropriated architecture. Hollywood both fascinates and repels; it's a foreign country to Allen as much as Rome or London or Spain.

And, with the artist's touch of Vittorio Storaro, Café Society is assuredly the most beautiful movie Allen has done since he and Gordon Willis parted ways...but in color, a popping, vivid color that suggests a 24 hour sunset (or what they call in the trade "The Magic Hour"). Not the rainbow Technicolor that Allen suggests in his opening narration (he's starting to sound his age), but Storaro's organic rich color from his work with Coppola and Bertolucci. It's a revelation that makes the most of Allen's compositions and Santo Loquasto's production design, which usually is invisible in Allen's lived-in world, but becomes exotic in the light of Storaro.

But where Allen lucks out is in the casting. He has gotten two very subtle transformative performances out of Eisenberg and Stewart, two young actors who've taken a lot of hits lately—Eisensberg for his manic, burbling Lex Luthor in Batman v Superman, Stewart for her "damsel" roles in Twilight and Snow White. These two are character actors, not stars. They have quirks and rough edges that make them interesting. If you scraped them down to the least common denominator to make them more palatable and A-list, they'd only become more dull.

They're anything but dull here. Stewart is the "Daisy" it's been impossible to recreate in the official "Gatsby" adaptations, undeniably smart but with the annoying tendency to be vapid in moments of comfort and leaning to the path of least resistance, inspiring the need to strangle in the same moment you want to hug her. She's capable of showing you the woman you want her to be, while steadfastly being the woman she wants to be, even if they're in opposition. That, in "Gatsby" has lead to a character seeming weak or indecisive, but Stewart never betrays that or her character. And Eisenberg does something amazing here. The temptation is to say he's the "Woody Allen stand-in" for this movie, but the character and the way he plays it belies that. Bobby is too smart, too forthright. He doesn't natter or stammer uncertainly, for all the puppyish enthusiasm at the beginning, he pretty much knows who he is and stays direct, which is far afield from Allen's typical characters. He doesn't waffle. And when conflicts come, if anything, he internalizes, going uncharacteristically quiet when confronted with Vonnie again, and when appraising his situation in the latter part of the movie, his eyes don't appear to be seeing, but looking inward, not looking for a way out, but trapped in a self-realization that paralyzes him. For all the talk of dreams and romance, those eyes betray a melancholic amusement at his own fallibility.

Allen is lucky to have these two. They raise Café Society out of its slim pretensions and give it a living, breathing soul.

No comments:

Post a Comment