or

"No, Assassinate. Murder Implies He Has a Life Worth Living."

When I first saw the trailer for Anthropoid (and it was on TV), I got excited. I knew the story from a fascinating book on the history of spies during World War II, "A Man Called Intrepid" by William Stevenson. One of its amazing stories is about the assassination (by Czech resistance fighters) of Reinhard Heydrich, a name (fortunately) lost to history, but at the time he was considered Hitler's right-hand man and eventual successor. Affectionately known as "the Hangman" and "the Butcher of Prague," he was Evil's "company man"—head of the Gestapo and the architect of The Final Solution, the eradication of Jews from the European continent.

If the Nazi's are the epitome of evil in the 20th Century, Heydrich was the worst of the worst, and the story of the conspiracy to kill him had all the hallmarks of a "Mission: Impossible" story, exciting, tense, in constant danger of being revealed and at great risk to those involved. The aftermath of the attempt was particularly grisly and Heydrich died a very slow, painful death (thankfully), but the assassination so enraged Hitler, he started a systematic, almost biblical, purge to punish the Czech populace, first ordering that 10,000 random citizens be rounded up for execution, and, when told this might be economically impractical, started the systematic execution of any Prague "suspects" and, acting on false intelligence, burned the nearby town of Lidice to the ground, killing all the males over 16 and sending the women and children to concentration camps. Similarly, in the town of Ležáky, every single adult was murdered.

|

| Heydrich's car after the assassination attempt. |

|

| The Lidice Children's memorial |

Sean Ellis is a London-based writer-director (and also cinematographer), mostly known for his short Cashback and its feature-length expansion. His co-author, Anthony Frewin, served as assistant to Stanley Kubrick for every film from 2001: a Space Odyssey to Eyes Wide Shut (with the sole exception of Barry Lyndon). With such a pedigree, it's not a surprise then, that Anthropoid is a solid film that manages to tell the story effectively while keeping the budget from going into the stratosphere (it was financed by British, French, and, of course, Czech production houses).

The film wastes no time, starting (after some archival footage and some back-story) with boots hitting the ground. Jan Kubiš (Jamie Dornan) and Josef Gabčík (Cillian Murphy), two Czechoslovakian fighters-in-exile, have just parachuted into Czechoslovakia, part of a nine man team trained in London to assassinate Heydrich as part of what has been termed "Operation: Anthropoid." Already things are not going well; Gabčík has landed in a tree, creating a deep laceration in his foot that will hobble him and keep him from moving far—they're a couple dozen kilometers from their destination of Prague. They're found by a local partisan who drives them to a nearby cabin. The two men are helpful and discuss what can be done with Gabčík's foot without attracting attention. It's a wonder, then, that when one of them goes into another room, they find him getting ready to use the phone. Maybe he's phoning a contact or maybe he's phoning for aid, but unannounced behavior is suspicious, and Gabčík wastes no time determining that the man was going to turn them in and shoots him. The other escapes leaving Kubiš to give chase. But, when it comes time to deliver the killing shot, his hand begins to shake in anxiety and the man gets away.

With an absconded truck, the two drive into Prague, seeking their contact. When they arrive at the appointed address, a nervous woman tells them he is no longer there, only giving them the address to a local veterinarian for Gabčík's foot, saying that he is "a good man."

Gabčík gets his foot sewn up and the vet offers them his office to stay the night. In the morning, they're visited by some of the Czech resistance, Vanek (Marcin Dorocinski) and "Uncle Hanjsky" (Toby Jones), who treat the two soldiers with a great deal of suspicion—their contact has been missing for weeks, abducted by the Gestapo, so seeing these two newcomers only heightens their worry; perhaps they're plants for the Nazi's. And when the two tell them their plan is to assassinate Heydrich, they immediately protest that the Czech government-in-exile has no idea the stranglehold the Nazi's have on the country and reprisals will certainly come of Heydrich's killing.

Despite resistance protests, Henjsky sets up Gabčík and Kubiš with a sympathetic family in Prague, so they can track Heydrich's movements and, being that he's a Nazi, that's easily done and they soon have alternate plans in place. Of the assassins, Kubiš is the cooler of the two, thinking on his feet, and able to improvise quickly. For instance, when Jan shows an interest in the family's maid (Charlotte Le Bon), Josef uses it, asking if she has a friend for him, so they can walk around the Prague streets without attracting the attention two lone males would attract in a country at work and at war. And when Anna shows up at a restaurant meeting with her friend Lenka (Anna Geislerová) dressed to the nines, Josef stages an embarrassing incident for the benefit of the Nazi officers whose attention has been attracted. It's a lesson she learns that pays off later in the movie.It's a handy talent to have, as with any plan, things can go wrong, plans change, signals mix and tensions increase. Ellis stays focused on the assassins in their preparations and hesitations; little time is spent on Heydrich—he is merely a target, a monster in human form and thus vulnerable. But, if Heydrich is vulnerable, they know that they are even more so, with the growing realization the longer they're in Prague, that they're on a suicide mission.

I want to address the dismissal of this film by members of the critical press, some of whom I respect, most I don't. There has been a lot of criticism of Ellis' hand-held cinematography during the early part of the film. That hand-held camera covers a lot of ground. The movement keeps things tense and changing in a beginning of the movie that is heavy on exposition and needs to set up a certain level of paranoia that will be the undercurrent for the entire film. In sequences where Josef is walking the street, suspecting every stationary male of being an informant, that hand-held is essential. The tightness of the shots helps to keep things focused and helps to focus on details appropriate to the period of the film, limiting the chances of showing something contemporary and taking you "out" of the film. It works well and lends the "discovery" portion of the film a certain energy. Perhaps the criticism is because it's actually NOTICED by these critics as opposed to the latest "Bourne" film (Greengrass' entire shooting style is to do this type of shot) or the "Star Trek" films where J.J. Abrams lends the film energy by basically hammering on the camera...and it never produces a mention.

I've also seen an awful lot of critics say the film is "dull." Really? It is, of course, a matter of opinion, but sometimes—as we've seen plenty this election year—an opinion can merely be just plain wrong. Maybe they've been de-sensitized to film rhythms that don't have a "tent-pole" action sequence every ten minutes. Maybe the constant "super-hero" crush has made these writers numb to indecision and human weakness. Maybe there aren't enough explosions. Maybe Michael Bay should have directed (why, Heydrich's car didn't even flip over—it didn't in reality, but when have films followed reality?). Much praise has been put on the film's last half-hour which provides plenty of action and quite a couple of explosions, and Ellis treats it with an ever more claustrophobic sense of dread. That stuff is hard to do. At least without being pretentious and arty about it. Or cavalier. Or worse, taking gratuitous glee in it.

It is nice to sit back and watch something where stuff matters, but doesn't serve as a prelude to a quip, a sneer, or a cheap laugh. There's been quite enough of that this Summer of Dogs in a seemingly endless spiral downward. I will heartily recommend a fine, professional film like Anthropoid, while the rest of the critics give better ratings to the likes of Sausage Party. Talk about the madness of the Mob.

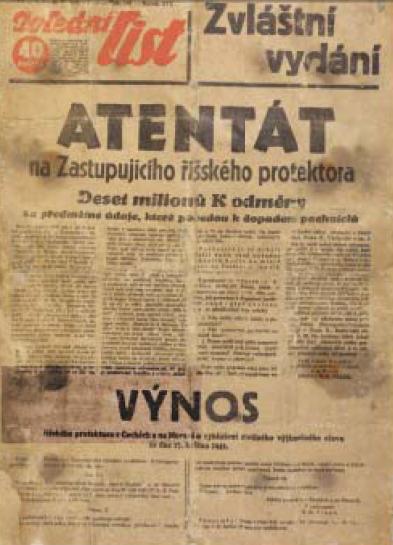

|

| The wanted poster for Heydrich's assassins. |

No comments:

Post a Comment