Not the best title for this piece, the last in the series of this overview of Alfred Hitchcock's career. Hitchcock was always Hitchcock, the director, with the foibles and eccentricities he'd developed growing up in England, and the perverse upbringing at the hands of his strict Catholic parents (Locking him in a jail-cell overnight and telling him "This is what we do to naughty boys." Nice). It's just this is the period, in Germany and England, when he was honing his film-making craft (with the assistance of the young script-woman behind him in the picture, Alma Revill, who the director married in 1926 and was his lifetime partner in life and art) before being enticed by David O. Selznick to Hollywood to fine-tune his pictures, and put a bit more of the extreme into them.

No. This is Hitchcock before he became "Hitchcock" the brand-name, identified with humorous thrillers that played on our fears and our psyches. This is Hitchcock before he took the gloves off and started peeling away the restraints, challenging what was presentable in films. There are shocks galore here, but only the bad guys didn't play by the rules.

Still, just as a child slowly grows into an adult while retaining the resemblance of that child, watching these early examples of the Master of Suspense when he was still an Apprentice of Suspense, you can see the beginnings of his "style," of the inventiveness that created the language of his films, the vocabulary of his mise en scéne—young Alfred Hitchcock wasn't afraid to try anything to push his audience in the direction he wanted to move them, and in his silent films, devoid of any dialogue, he pushed how the still young medium was capable of communicating through image, not just in what it showed, but how it showed it.

Jamaica Inn (1939) The first of Hitchcock's adaptations of stories by Daphne DuMaurier (the other's would be his next film Rebecca, and 1963's The Birds) was also the last of his British pictures. DuMaurier's story is a gothic tale of a young innocent lass Mary Yellen (introducing Maureen O'Hara), recently orphaned and sent to live with an aunt at the notorious Jamaica Inn in Cornwall. Everyone warns her not to go, including the carriage driver who drops her off before her destination rather than go there. The reputation of the place precedes her, with stories of vessels being carried to their doom. The truth is less strange—seems it's a haven of cut-throats who cut off any coastal beacons to drive ships to their doom on the rocks, plundering the spoils and killing all hands. An investigator (Robert Newton) has infiltrated the pirates and is close to discovering who the ring-leader is, all fingers pointing to the inn-keeper of the Jamaica Inn, who just happens to be married to the woman who is Mary's aunt, and in whose care Mary now lives. Subterfuge is on top of subterfuge, as is the case with so many Hitchcock films.

It was not the happiest experience for Hitchcock, as it was one of those that tainted his opinion of "certain" actors. Charles Laughton was a big star of British film and screen (and co-producer of the film), and insisted that O'Hara be cast, and extensively exerted control over the production, having his role extensively re-written (from vicar Francis Davey to Sir Humphrey Pengallion) and portraying it in a way that Hitchcock found too obvious and revealing for the purposes of the film. The historical reputation of the film is far worse than it deserves (Harry Medved put it in his tome "The Fifty Worst Films of All Time," inexplicably), but it isn't prime Hitchcock. And it was his last film before leaving Britain and taking a job as a contract director for producer David O. Selznick in Hollywood, which would be his base of operation until his death.

|

| Maureen O'Hara is a plucky lass in Hitchcock's last British production. |

The Lady Vanishes (1938) Poor Iris Matilda Henderson has "been everywhere and done everything," and is on her way to marry what her traveling companions call a "blue-blooded check-chaser" when she gets beaned by a suspiciously-un-anchored flower box. She is helped onto her departing train and administered to by the elderly Miss Froy, a vacationing governess in love with the music of the Alps. Waking up from a recuperative nap, Iris discovers the woman missing, and what's worse, no one on the train claims to have seen her. Is everyone on the train lying, or has Iris just imagined the whole thing? The only ally she can find is the eccentric and rather obnoxious musicologist (Michael Redgrave, father of Lyn and Vanessa, and grandfather of Joely Richardson), whose racket has kept her awake nights at their lodgings. But now he comes to her aid ("My father taught me to never desert a lady in trouble. In fact I think that's why he married my mother!") to determine just what's been lost—the old lady or Iris' mind. Redgrave supposedly didn't get on with Hitchcock, and didn't have much respect for movie-acting, either—until another cast member saw him on-stage and wondered why he was so brilliant on the boards and so lackluster on-screen. For his part, Hitchcock took the material and accentuated the comedy and sexual situations, giving each of the train participants their own contrary behavior. It proved to be one of the most beloved of Hitchcock's British films, and legitimately can stand up to any of "The Master of Suspense's" later classics.

Cameo: Hitchcock smokes a cigar and comically hunches his shoulders at Victoria Station @ 1:32:31.

|

| The vision of Mrs. Froy superimposed over Iris' face. |

Young and Innocent (aka The Girl was Young, 1937) Writer Robert Tisdell (Derrick DeMarney) witnesses star Christine Clay's body wash up on the beach, and he is immediately accused of murdering her by witnesses. She was, after all, strangled with the belt of a coat he once owned. And the two were previously lovers. But, he is one of Hitchcock's many "wrong men," who, despite protesting his innocence, faces imprisonment and possibly hanging. He goes on the lam, his means of escape happening to be the Morris owned by the Chief Constable's daughter, Erica (Nova Pilbeam, the kidnapped daughter in The Man Who Knew Too Much). Not well-planned. Neither is the romance that develops between the two, the young and the innocent. As things develop, the two must come to grips with two clues—finding that damned raincoat that was once stolen from Tisdell, and identifying the man who stole it, a fellow with anger-management issues and an obvious "tell," his manically twitching eyes. One can already see that there are coincidences galore in the film ("Then there wouldn't be a moooovie" one can hear Hitchcock defending), but there are some nice little set-pieces throughout: an escape and rescue into an abandoned mine; complications arising from a child's birthday party; an amusing pub scene; and an extended denouement at The Grand Hotel, featuring jazz music and an early bravura camera move across the dance hall's vast space to land on a pair of severely twitching eyes, quite a few years before Hitchcock would travel a long way to focus on a single key in Notorious.

Cameo: Hitchcock's a photographer trying unsuccessfully to take a picture outside the courtroom @ 16:00.

Sabotage (aka The Woman Alone, 1936)  A free adaptation of Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Agent," (as opposed to the earlier film of the same name) this one has John Loder as a police investigator posing as a green grocer to keep an eye on a movie theater run by Karl Verloc (Oscar Homolka), who, in his spare time is a runner for a terrorist organization setting off bombs in London. His wife (Sylvia Sidney) begins to suspect after a lot of questions are asked by Loder, and after an incident in which her young brother is used to deliver bombs (disguised in film cans) to the London Underground under Piccadilly Circus (one of the great nail-biting sequences in all of Hitchcock's films). There are contrivances throughout, but this is one of the best of Hitchcock's early films, daring and more than a little cold-blooded, testing its audience's loyalties and their pressure points, while also slyly making comments on the action through the clips (provided by Disney) shown in the cinema. This is one of those Hitchcock movies that is absolutely timeless.

A free adaptation of Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Agent," (as opposed to the earlier film of the same name) this one has John Loder as a police investigator posing as a green grocer to keep an eye on a movie theater run by Karl Verloc (Oscar Homolka), who, in his spare time is a runner for a terrorist organization setting off bombs in London. His wife (Sylvia Sidney) begins to suspect after a lot of questions are asked by Loder, and after an incident in which her young brother is used to deliver bombs (disguised in film cans) to the London Underground under Piccadilly Circus (one of the great nail-biting sequences in all of Hitchcock's films). There are contrivances throughout, but this is one of the best of Hitchcock's early films, daring and more than a little cold-blooded, testing its audience's loyalties and their pressure points, while also slyly making comments on the action through the clips (provided by Disney) shown in the cinema. This is one of those Hitchcock movies that is absolutely timeless.

A free adaptation of Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Agent," (as opposed to the earlier film of the same name) this one has John Loder as a police investigator posing as a green grocer to keep an eye on a movie theater run by Karl Verloc (Oscar Homolka), who, in his spare time is a runner for a terrorist organization setting off bombs in London. His wife (Sylvia Sidney) begins to suspect after a lot of questions are asked by Loder, and after an incident in which her young brother is used to deliver bombs (disguised in film cans) to the London Underground under Piccadilly Circus (one of the great nail-biting sequences in all of Hitchcock's films). There are contrivances throughout, but this is one of the best of Hitchcock's early films, daring and more than a little cold-blooded, testing its audience's loyalties and their pressure points, while also slyly making comments on the action through the clips (provided by Disney) shown in the cinema. This is one of those Hitchcock movies that is absolutely timeless.

A free adaptation of Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Agent," (as opposed to the earlier film of the same name) this one has John Loder as a police investigator posing as a green grocer to keep an eye on a movie theater run by Karl Verloc (Oscar Homolka), who, in his spare time is a runner for a terrorist organization setting off bombs in London. His wife (Sylvia Sidney) begins to suspect after a lot of questions are asked by Loder, and after an incident in which her young brother is used to deliver bombs (disguised in film cans) to the London Underground under Piccadilly Circus (one of the great nail-biting sequences in all of Hitchcock's films). There are contrivances throughout, but this is one of the best of Hitchcock's early films, daring and more than a little cold-blooded, testing its audience's loyalties and their pressure points, while also slyly making comments on the action through the clips (provided by Disney) shown in the cinema. This is one of those Hitchcock movies that is absolutely timeless. .jpg) The Secret Agent (1936) "May 10th, 1916. 84 Curzon St. W." say the opening titles. There, a funeral is held for heads of the military. But the coffin is empty**. Based on "Ashenden" by W. Somerset Maugham, it traces the story of one Captain Edgar Brodie (John Gielgud) recruited by the British Secret Service (and it's head, "R") to cross over, under the alias "Richard Ashenden," to "Switzerland to locate a certain German agent who's about to leave for Arabia very shortly by way of Constantinople." "Ashenden" poses as a married man with fellow agent Elsa Carrington (Madeleine Carroll), who is being pursued by charming American Robert Marvin (Robert Young, showing some real range), who doesn't seem to care about the "arranged" marriage. The two agents eventually fall in love, but the nasty business of murder for hire spoils the romance. Some of Hitchcock's stylish moments: A murder committed through telescope, the victim's dog howling at his demise, a chocolate factory (they're in Switzerland) that's described by operative "The General" (real name: General Pompellio Montezuma De La Vilia De Conda De La Rue, played by Peter Lorre) as "The Big German Spy Post Office," and the big confrontation with the villain that's interrupted by a train-wreck, even a scene in a casino. Lorre is at his playful best, Gielgud restrained and urbane, but Young and Carroll are the real charmers here.

The Secret Agent (1936) "May 10th, 1916. 84 Curzon St. W." say the opening titles. There, a funeral is held for heads of the military. But the coffin is empty**. Based on "Ashenden" by W. Somerset Maugham, it traces the story of one Captain Edgar Brodie (John Gielgud) recruited by the British Secret Service (and it's head, "R") to cross over, under the alias "Richard Ashenden," to "Switzerland to locate a certain German agent who's about to leave for Arabia very shortly by way of Constantinople." "Ashenden" poses as a married man with fellow agent Elsa Carrington (Madeleine Carroll), who is being pursued by charming American Robert Marvin (Robert Young, showing some real range), who doesn't seem to care about the "arranged" marriage. The two agents eventually fall in love, but the nasty business of murder for hire spoils the romance. Some of Hitchcock's stylish moments: A murder committed through telescope, the victim's dog howling at his demise, a chocolate factory (they're in Switzerland) that's described by operative "The General" (real name: General Pompellio Montezuma De La Vilia De Conda De La Rue, played by Peter Lorre) as "The Big German Spy Post Office," and the big confrontation with the villain that's interrupted by a train-wreck, even a scene in a casino. Lorre is at his playful best, Gielgud restrained and urbane, but Young and Carroll are the real charmers here.Lorre, Gielgud, Carroll, and Young

The 39 Steps (1935) Shots are fired at a music-hall performance by "Mr. Memory," and Canadian Richard Hannay (Robert Donat) escorts a mysterious woman back to his apartment, who avoids the windows and doesn't want Hannay to answer his phone. She's the one who fired those shots. "Sounds like a spy story," offers an amused Hannay. Just so. She speaks cryptically of an international plot led by a man with a deformed pinky finger and "the thirty-nine steps" and promises to tell him about it in the morning. Well, never put off tomorrow what you can do today, because during the night she is stabbed in the back, murdered. Hannay escapes from the city by train, and hightails it to Scotland, a doctored map of same being the only clue the murdered spy leaves him. From then on, Hannay can't trust anyone or anything as he runs one step ahead of the police and Scotland Yard, and for a bit hand-cuffed to the Hitchcock blond-love-interest-plot-sounding board Madeleine Carroll, who, true to directorly form, starts out suspecting the worst and hating Hannay, then falls in love with him, due to his pluck and ingenuity. The themes would run through Hitchcock's filmography right up to the end, but the details and tricks would evolve over the decades (this one, for example, has an ingenious way to store hidden plans and smuggle them out of the country). One of Hitchcock's all-time classics.

Cameo: Hitchcock walks in front of a bus, throwing litter @ 06:56.

|

| Robert Donat borrows a newspaper in which he's the headline. |

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) What was intended to be a Bulldog Drummond adaptation turned into Hitchcock taking his story elements and turning them into an original film about innocents abroad (Leslie Banks, Edna Best)being tipped off to a murder plot, and to keep them silent, the conspirators kidnap their daughter. If they go to the police, their daughter will be killed, and so they endeavor to foil the plot themselves, risking being arrested as the conspirators. Hitchcock hired Peter Lorre, who had just become a sensation in Fritz Lang's M, to play the part of conspirator Louis Bernard, which he played phonetically, having just fled Nazi Germany and being unable to speak English. As in the Hitchcock-directed 50's remake, the assassination is to take place at the Royal Albert Hall, and Hitchcock commissioned Arthur Benjamin to write a piece specifically for the film (that had to have a sufficiently loud percussion crash to mask a gunshot). That piece, "The Storm Clouds Cantata," was also performed in Hitchcock's 50's remake starring James Stewart and Doris Day. Although 20 years apart, it's hard to pick which is the better, or even favorite, version, but I might have to go with this one.

Cameo: Hitchcock walks in front of a passing bus @ 25:42.

Waltzes from Vienna (aka Strauss' Great Waltz, 1934) A biography of Johann Strauss Jr. and part of a cycle of operetta films made in Germany and Britain during the 1920's and 1930's. Hitchcock considered Waltzes From Vienna "the low ebb" of his career—he took it as a job, with his only interest being how he could compose the sequence for the premiere of "By the Beautiful Blue Danube" to take advantage of the merging of music and picture to present something that enhanced both.

It's a film more suited towards Ernst Lubitsch than Hitchcock, but one would imagine that Lubitsch might make it a bit saucier, instead of the light comedy presented here. The story is complete fiction: No, Strauss didn't write "The Blue Danube" first; no, it wasn't a huge success from the debut (even Strauss didn't like it much); no, it was originally written as a song for the Vienna Men's Choral Association; no, the lyrics were not written by a Countess, who was seen as a romantic rival by Strauss' fiancee; no, the fiancee wasn't a baker's daughter who whined all the time; and no, Strauss did not come up with the melody while watching baker's make bread. That's all schnitzel.

It is true that there was a bit of a rivalry between Strauss Sr. and Strauss Jr., but that's about it. In the meantime, the film is all froth and no beer. Yes, some of the writing is clever—the scene of the servants being go-between's for the across-rooms conversation of the Count and Countess ("What rhymes with orange" "Lozenge" "Idiot." "What color is the Danube?" "A sort of dirty-brown..") while they're enjoying a little romance is funny, but the rest is sophomoric, a bit too convenient and by-the-numbers. Or perhaps it should be "by the sheet-music."

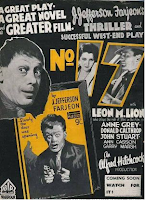

Number 17 (1932) Property assigned to Hitchcock after it proved a hit on the London stage, but in the book-length interview "Hitchcock/Truffaut," the director described it as "a disaster." It is a bit, set (at least initially) in your typical "old, dark house" with lots of shadows and staircases, the place, while previously abandoned, is soon filled with an awful lot of people, very few of whom being what they claim. Beautifully shot, with a lot of subdued lighting, the editing is sometimes marked by an overabundance of quick cuts, which work well during a stair-running sequence and a fight (that recalls the energy in the one from From Russia With Love and employs a very early example of foley work), but the movie goes on to a logistical nightmare that Hitchcock pulls off quite admirably—a chase on a train. Employing models and full-size versions, both stationary and moving, he manages to keep the momentum going for another 30 minutes, while the "MacGuffin" of the story is nearly all but forgotten. A trifle for the punters, with some note-worthy work embedded.

Cameo: Hitchcock is on the runaway bus @ 51:25.

It's a film more suited towards Ernst Lubitsch than Hitchcock, but one would imagine that Lubitsch might make it a bit saucier, instead of the light comedy presented here. The story is complete fiction: No, Strauss didn't write "The Blue Danube" first; no, it wasn't a huge success from the debut (even Strauss didn't like it much); no, it was originally written as a song for the Vienna Men's Choral Association; no, the lyrics were not written by a Countess, who was seen as a romantic rival by Strauss' fiancee; no, the fiancee wasn't a baker's daughter who whined all the time; and no, Strauss did not come up with the melody while watching baker's make bread. That's all schnitzel.

It is true that there was a bit of a rivalry between Strauss Sr. and Strauss Jr., but that's about it. In the meantime, the film is all froth and no beer. Yes, some of the writing is clever—the scene of the servants being go-between's for the across-rooms conversation of the Count and Countess ("What rhymes with orange" "Lozenge" "Idiot." "What color is the Danube?" "A sort of dirty-brown..") while they're enjoying a little romance is funny, but the rest is sophomoric, a bit too convenient and by-the-numbers. Or perhaps it should be "by the sheet-music."

Number 17 (1932) Property assigned to Hitchcock after it proved a hit on the London stage, but in the book-length interview "Hitchcock/Truffaut," the director described it as "a disaster." It is a bit, set (at least initially) in your typical "old, dark house" with lots of shadows and staircases, the place, while previously abandoned, is soon filled with an awful lot of people, very few of whom being what they claim. Beautifully shot, with a lot of subdued lighting, the editing is sometimes marked by an overabundance of quick cuts, which work well during a stair-running sequence and a fight (that recalls the energy in the one from From Russia With Love and employs a very early example of foley work), but the movie goes on to a logistical nightmare that Hitchcock pulls off quite admirably—a chase on a train. Employing models and full-size versions, both stationary and moving, he manages to keep the momentum going for another 30 minutes, while the "MacGuffin" of the story is nearly all but forgotten. A trifle for the punters, with some note-worthy work embedded.

Cameo: Hitchcock is on the runaway bus @ 51:25.

Rich and Strange (aka East of Shanghai, 1931) An odd comedy of manners about a bored English bickering couple (Henry Kendall, the exquisite Joan Barry) who learn the bad side of good fortune. An uncle telegrams them bequeathing money to them for the purposes of their enjoying themselves. They decide to take a cruise "to the Orient," but instead of enjoying themselves they must battle sea-sickness, culture shock and the temptations outside the marriage. By the time they hit Rangoon, they're both ready to divorce each other for other, more interesting people. Both of those parties are not whom they claim, and the hapless couple end up being robbed, with just enough money from the Uncle's advance to take a tramp steamer home...which ends up colliding with another ship in the fog. The two are trapped in their room, sure that they will drown, when they are rescued by pirates.

Rich and Strange (aka East of Shanghai, 1931) An odd comedy of manners about a bored English bickering couple (Henry Kendall, the exquisite Joan Barry) who learn the bad side of good fortune. An uncle telegrams them bequeathing money to them for the purposes of their enjoying themselves. They decide to take a cruise "to the Orient," but instead of enjoying themselves they must battle sea-sickness, culture shock and the temptations outside the marriage. By the time they hit Rangoon, they're both ready to divorce each other for other, more interesting people. Both of those parties are not whom they claim, and the hapless couple end up being robbed, with just enough money from the Uncle's advance to take a tramp steamer home...which ends up colliding with another ship in the fog. The two are trapped in their room, sure that they will drown, when they are rescued by pirates.

The punch-line is that after so many disasters that make them realize how good they've got it, when they return home, they're still the same as they were at the beginning of the movie...bored and dissatisfied.

One sees that Hitchcock has loosened up considerably after the staginess of Juno and the Paycock, and as with Blackmail, he takes the added dimension of sound and starts to play with it, as is demonstrated in an early scene in a traffic jam, which is a combination of on-set and post-production sound.

But things settle down to a war over land between the "old money" Hillcrest's (headed by C.V. France and Helen Haye)—who have hit a rough financial patch—and the "nouveau riche" Hornblower family (headed by Edmund Gwenn). There is a single parcel of land abutting the Hillcrest's property that they would like to leave unspoiled, while Hornblower wants to develop it and put in factories. The two families bray and sniff at each other, to the point where it affects the second generation of both families. There is a lovely auction sequence for the land that Hitchcock manages to make ingenious (including a nice little joke about sound films, when a clerk reading the description of the parcel is barely audible—if we'd been able to hear him it would have been dull, but as it is it's pretty funny) through all sorts of means, and there's a bizarre special effect early in it that we only figure out after another 30 minutes of disclosure.

The lesson is "rich" doesn't make you aristocratic, future generations pay for the sins of their forebears and one reaps what one sews. It's a fine adaptation and Hitchcock is in fine form. Also that the road to Hell is paved (paved, mind you) with good intentions.

|

| Hitchcock employs action on three planes in The Skin Game. |

Murder! (1930) What is truth and what is fiction in the murder of actress Edna Druce? The accused is fellow-actress Diana Baring (Norah Baring), caught "practically red-handed." "Girl's dress all over, blood. The poker at her feet. Brandy glass empty, and the girl's half silly." At Norah's trial, jurist Sir John Menier (Herbert Marshall) is convinced to change his vote from "not guilty" to "guilty" at the girl's trial, despite the lack of circumstantial evidence and takes it upon himself to conduct his own investigation, while Baring awaits the gallows. He recruits fellow actors and the police to check the scene of the crime and interview the cast of character witnesses. His reputation as a stage star and theatrical entrepreneur opens many doors and weakens many an artistic ego wanting to work with the man, never suspecting that he might be laying a trap for a murderer. Hitchcock's third "talkie" has many more experiments with sound and overlapping dialog, and he takes less chances with camera movement and effects, although the denouement at a circus features a creative series of shots from a trapeze artist's point of view. The explanation is a little rushed and "on the nose," but it would not be the last time that Hitchcock would rush the explanations at the end in order to keep the pace up of the puzzle.

Cameo: Hitchcock walks in front of the camera @ 59:55.

Juno and the Paycock (aka The Shame of Mary Boyle, 1929) Not sure why the U.S. version has the more blunt title—Mary Boyle plays a small part in Sean O'Casey's classic play ("adapted" by Hitchcock with "scenario by Alma Reville") about life among the poor Irish during the Irish war of Independence in the early decades of the 20th Century. With the exception of the beginning (featuring Barry Fitzgerald in his film debut, but not playing the starring role he played on stage in this) and a diversion at a pub, the screenplay is stage-bound and one can see Hitchcock—maybe for the only time in his career—a bit ham-strung with this one—the bulky sound cameras were tough to move around...and noisy which would interfere with dialogue tracks. So, this movie concentrates on acting and mise en scene with many long takes which makes it feel more like a filmed play—which it is. Captain Jack Boyle (Edward Chapman) lives in an Irish tenement with his wife Juno (Sara Allgood), crippled son Johnny (John Laurie) and daughter Mary (Kathleen O'Regan). Juno is the only one of the family who works, Mary being on strike, Johnny being in no shape to work after fighting with the "Black and Tans" and the Captain usually being found drinking, fulminating and complaining of not being able to work due to leg injuries from his career as a merchant seaman.

Blarney, and full to the brim of his captain's hat with it.

Cap'n Jack finds out from a lawyer (John Longden) that he has been remembered in a relative's will and life becomes good. They buy things, start loaning friends money, and Mary starts seeing that lawyer. They can even forget about the machine gunning going on outside their door as friends and neighbors are attacked and killed by British soldiers. O'Casey is making a point about the Irish ability to look for a pony in a pile of manure, to live large while the living is good, even in the face of disaster. That's all well and good, but when disaster does strike, the fall from the heights of delight or delusion are precipitous. The play is more psychological than one might suspect, and Hitchcock brings out fairly subtle, if florid, performances from his cast, the stand-out being Allgood, who has never been bad.

|

| Chapman, Allgood, Sidney Morgan, and Maire O'Neill living large. |

Blackmail (1929) Hitchcock has energy to burn right from the beginning of this tale of a duplicitous girl who finds herself more than compromised in Hitchcock's first complete sound picture (a combination of silent parts with post-synced sound and some sequences with live stage recording). The film begins with a chase as New Scotland Yard detectives are tracking down a criminal, trap him in his apartment and take him downtown. That's when one of the detectives, Frank Webber (John Longdon) meets up with shop-girl Alice White (German actress Anny Ondra, but voiced off-screen by Joan Barry) for a date. A spat breaks things up, and Frank is chagrined to find that Alice leaves with another bloke (Cyril Ritchard). That bloke is an artist who invites Alice up to his flat to presumably look at his etchings, but as intrigued as she is with him, he has other intentions, and while she struggles to keep her virtue, ends up killing him with a bread-knife.

One of the investigators turns out to be her old beau Frank Webber, who finds one of Alice's gloves at the scene of the crime. The other is in the hands of one of the artist's models, a blackmailer named Tracy (Donald Calthorp), who is only too eager to press his own advantage. This is a murder investigation without the innocence of so many of Hitchcock's protagonists—in this case, she's guilty, although in self-defense—but the terror is no less real, and the director uses a lot of neat tricks with cutaway staircases, super-impositions, and match-cuts, and his work with shadows and dramatic lighting are in full display. Hitchcock also experiments with the sound; for example, after the murder a discussion of the crime by one of the shop's patrons goes into mumbles except whenever the word "knife" is mentioned. Lots of interesting things in this one.

Cameo: Hitchcock is trying to read a book on the Underground while being harassed by a curious child @ 10:25.

|

| Blackmail ends with a chase through The British Museum, requiring some tricky FX |

Hitchcock and Anny Ondry do a test-take for sound (and Hitch tells a dirty joke)

Then, Pete goes missing in the jungle—presumed dead, and the two run into each other's arms in consolation. Actually, it's a grainery above the pub, and Hitchcock employs one of the oddest of sexual stand-in's—a grinder—to invoke activity the censors would not allow. That seals the deal and seals their fate, as the course of love never runs smooth and justice is blind; you'd think a fisherman and a judge would know those things.

Despite the melodrama, most of the actors—Brisson being the sole exception, despite having great moments—the actors shine in this, as Hitchcock's final silent film shows him combining his best techniques and subtle direction to still manage to get the point across with a lack of title cards. And Anny Ondry can be said to be the prototypical "Hitchcock blonde."

|

| The locals get an eyeful of scandal in The Manxman |

Champagne (1928) Hitchcock does a change of pace with one of his few forays into an out-and-out comedy (there is always a droll sensibility to his films, even a puckishness, but it's usually there to leaven the drama or spice up long dialogue sections). "The girl" (Betty Balfour) is a rich socialite who thinks nothing of taking her Wall Street tycoon of a Dad's "aeroplane" and crashing it in the ocean, just so she can catch an ocean liner (run by Cunard) that her callow boyfriend (Jean Bradin) is on. He is non-plussed by the extravagant show of affection, and further miffed that she shows interest in a man who shows a lot of interest in her (Theo Van Alten). Her Father (Gordon Harker), annoyed at his daughter's shenanigans, shows up on-ship to tell her (in the middle of an extravagant party in her room) that he's bust—his distraction by her has turned the sharks of Wall Street against him. Even on a cruise-ship, the tide can turn.

Father and daughter live in Paris in a meager apartment, as she learns how "the other half" lives and, determined to take care of Dad, she decides to take a job as a flower-girl in a wild nightclub. But, her past catches up with her as first the boyfriend and then the "interested" man from the cruise ship re-enter her life.

It's slight, with a central conceit that Hitchcock telegraphs fairly early on and the film lives and dies on how charming one thinks Balfour is—she's cute and a natural actress, even in silent films. And, again, Hitchcock uses a minimum of dialogue cards and some elaborate camera tricks to tell his story.

Later in life, he would describe this as his least favorite film, but it's not bad.

Easy Virtue (1928) Noël Coward play directed by Hitchcock. You'd think the least successful thing in the world would be a silent version of a Coward play, given the wit and dialogue that could only be consigned to title-cards. As it is, Hitchcock, working with a script by Elliott Stannard, with most of that repartee gone, relegates what part of the drawing-room shenanigans left to him to the last half of the movie; the first half is taken up by the back-story of Larita Filton (Isabel Jeans, working again with Hitchcock), the happenstance behind the divorce of her first husband, her subsequent fleeing of the glaring limelight to Cannes, and her meeting with John Whittaker (Robin Irvine, again), the eager young heir of the very wealthy, very snooty Whittaker "people." Whittaker falls madly in love and against her better judgment, Larita accepts his marriage proposal.

They make their way back to the family estate, where Mrs. Whittaker (Violet Farebrother) is not pleased...not very pleased at all...that John has gone off and married some woman without her knowledge or consent. His father (Frank Elliott), however, seems unconcerned, sure that she is "an interesting woman." From then on, things turn mightily passive-aggressive as Whittaker's family (save her father) take every opportunity to sour the marriage...and do so rather successfully.

One can start to see the Hitchcock "3-shot" come into existence here—the deliberately rhythmed inter-cutting of "look-see-react" (less apparent in The Farmer's Wife, although it is there), and although stylized, the acting still has a more natural feel to it than Hitchcock's first works. When the director is so present in communicating his intent, too much emoting seems unnecessary, and Hitchcock very quickly made adjustments in how he was handling actors.

Cameo: Hitchcock leaves a tennis court @ 21:15.

Father and daughter live in Paris in a meager apartment, as she learns how "the other half" lives and, determined to take care of Dad, she decides to take a job as a flower-girl in a wild nightclub. But, her past catches up with her as first the boyfriend and then the "interested" man from the cruise ship re-enter her life.

It's slight, with a central conceit that Hitchcock telegraphs fairly early on and the film lives and dies on how charming one thinks Balfour is—she's cute and a natural actress, even in silent films. And, again, Hitchcock uses a minimum of dialogue cards and some elaborate camera tricks to tell his story.

Later in life, he would describe this as his least favorite film, but it's not bad.

|

| During an interview for his last film, Family Plot, Hitchcock mentioned that Champagne was the least favorite of his films: "It didn't have a finished script!" |

Easy Virtue (1928) Noël Coward play directed by Hitchcock. You'd think the least successful thing in the world would be a silent version of a Coward play, given the wit and dialogue that could only be consigned to title-cards. As it is, Hitchcock, working with a script by Elliott Stannard, with most of that repartee gone, relegates what part of the drawing-room shenanigans left to him to the last half of the movie; the first half is taken up by the back-story of Larita Filton (Isabel Jeans, working again with Hitchcock), the happenstance behind the divorce of her first husband, her subsequent fleeing of the glaring limelight to Cannes, and her meeting with John Whittaker (Robin Irvine, again), the eager young heir of the very wealthy, very snooty Whittaker "people." Whittaker falls madly in love and against her better judgment, Larita accepts his marriage proposal.

They make their way back to the family estate, where Mrs. Whittaker (Violet Farebrother) is not pleased...not very pleased at all...that John has gone off and married some woman without her knowledge or consent. His father (Frank Elliott), however, seems unconcerned, sure that she is "an interesting woman." From then on, things turn mightily passive-aggressive as Whittaker's family (save her father) take every opportunity to sour the marriage...and do so rather successfully.

One can start to see the Hitchcock "3-shot" come into existence here—the deliberately rhythmed inter-cutting of "look-see-react" (less apparent in The Farmer's Wife, although it is there), and although stylized, the acting still has a more natural feel to it than Hitchcock's first works. When the director is so present in communicating his intent, too much emoting seems unnecessary, and Hitchcock very quickly made adjustments in how he was handling actors.

Cameo: Hitchcock leaves a tennis court @ 21:15.

The Farmer's Wife (1928) Samuel Sweetland (Jameson Thomas) has suffered two devastating emotional blows recently: the death of his wife Tippy and the marriage of his daughter and her moving out of his house and his life. Now an empty-nester (except for his servants 'Minta—played by Lillian Hall-Davis—and Ashe—played by Gordon Harker), and feeling that his life isn't over, he determines that he will marry again. With 'Minta's help, he draws up a list of eligible town-women and is shocked and dismayed to find out that none of them (for various reasons) want to marry him.

A gentle rural comedy, based on a successful play, it seems atypical Hitchcock, but he manages enough visual trickery for story-telling effect (particularly when Sweetland imagines blissful domestic life as a ghostly fade-in to the now-empty chair by the fire). But, there has been a subtle sea-change between production of Downhill and The Farmer's Wife: freed from Ivor Novello's melodramatics, the acting here is subtle, particularly from Thomas (although surprise is conveyed with a single sharply raised eyebrow) and Hall-Davis. It's like they actually believe the camera can capture what they're thinking (and, of course, it can). The "silent treatment" (the over the top kind) is relegated to the character actors, as a means to emphasize their eccentricities and (among the prospective brides) why they might not be suitable matches. The visual touches are frequently ingenious (a nervous type is shown holding a plate of quivering jelly-mould) as usual, but Hitchcock doesn't overwhelm the story with too many fluorishes. And there is a jump in the number of dialogue cards used as some of them have colorful declarations that go beyond the obvious and have their own inherent enjoyment.

A gentle rural comedy, based on a successful play, it seems atypical Hitchcock, but he manages enough visual trickery for story-telling effect (particularly when Sweetland imagines blissful domestic life as a ghostly fade-in to the now-empty chair by the fire). But, there has been a subtle sea-change between production of Downhill and The Farmer's Wife: freed from Ivor Novello's melodramatics, the acting here is subtle, particularly from Thomas (although surprise is conveyed with a single sharply raised eyebrow) and Hall-Davis. It's like they actually believe the camera can capture what they're thinking (and, of course, it can). The "silent treatment" (the over the top kind) is relegated to the character actors, as a means to emphasize their eccentricities and (among the prospective brides) why they might not be suitable matches. The visual touches are frequently ingenious (a nervous type is shown holding a plate of quivering jelly-mould) as usual, but Hitchcock doesn't overwhelm the story with too many fluorishes. And there is a jump in the number of dialogue cards used as some of them have colorful declarations that go beyond the obvious and have their own inherent enjoyment.

Downhill (aka When Boys Leave Home, 1927) Hitchcock starts with an opening card: "Here is a tale of two school-boys who made a pact of loyalty. One of them kept it—at a price." Young scion Roddy Berwick (Ivor Novello) is a promising scholar and footballer at an exclusive prep school. He and best friend Tim Wakely (Robin Irvine) are inseparable, even, apparently, to seeing a waitress (Annette Benson), who ultimately brings up charges to the school that one of them has made her pregnant. In a confrontation at the headmaster's office, she accuses Roddy (it was actually Tim) and young Berwick is expelled. He remains silent as Tim would be ruined, losing the scholarship that would get him to Oxford—as opposed to Roddy, Tim's father is a reverend and cannot "buy" schools. Returning home to the family, manse, the elder Berwick (Norman McKinnel) is aghast at the accusation and disowns Roddy, setting him adrift to make his own way in the world. That world is not kinder to Roddy—starting out as an actor (starting out as an actor?), where, thanks to a sudden unexpected inheritance, he's emboldened to wed the leading lady (Isabel Jeans) of the play he's in.

The play this is based on was actually co-written by Novello (under the name David LeStrange with Constance Collier—who would appear in Hitchcock's Rope) and Hitchcock does what he can with it, visually—although one internet commenter noted: "If I have to see another character go downstairs..."— the downward spiral that Roddy follows is remarkably non-spiralling and far more angular, but instead of "Money is the root of all evil" being a theme, it is "women are the root of all trouble." Roddy's downfall comes at the actions, and in the reflection of...women—they're very one-dimensional in this, with suspect motivations. Things were so much simpler in the ivory towers of the boys' school. It's the main problem with the film, and Hitchcock (who appears not to have Alma Reville looking over his shoulder on this one) would become less discriminating in his material and more discriminating in choosing it.

The Ring (1927) Hitchcock's only original screenplay credit, and even at this stage of the game, his fifth film, his story-telling abilities are sophisticated, his humor dark and slightly sarcastic, and his voyeuristic themes are showing through. "One Round" Jack Sander (Carl Brisson) is a "winner-take-all" boxer at a sideshow carnival. He's undefeated until Bob Corby (Ian Hunter) is attracted to the tent by Sander's pretty fiance (Lillian Hall-Davis) Corby knocks Sanders down (the "round" cards is a clever Hitch bit—the first one is in disrepair and slides into the display easily, but the seldom-used second one looks new and has difficulty going in). Sanders becomes Corby's sparring partner, but seeing how Corby still has eyes for his girl, he works his way up in the standings so he can have one more shot at his rival, inside and outside the ring. Very nice work here, and one starts to realize many minutes in, how few title cards Hitchcock depends on to tell his story. It's all in the images and their details.

The play this is based on was actually co-written by Novello (under the name David LeStrange with Constance Collier—who would appear in Hitchcock's Rope) and Hitchcock does what he can with it, visually—although one internet commenter noted: "If I have to see another character go downstairs..."— the downward spiral that Roddy follows is remarkably non-spiralling and far more angular, but instead of "Money is the root of all evil" being a theme, it is "women are the root of all trouble." Roddy's downfall comes at the actions, and in the reflection of...women—they're very one-dimensional in this, with suspect motivations. Things were so much simpler in the ivory towers of the boys' school. It's the main problem with the film, and Hitchcock (who appears not to have Alma Reville looking over his shoulder on this one) would become less discriminating in his material and more discriminating in choosing it.

The Ring (1927) Hitchcock's only original screenplay credit, and even at this stage of the game, his fifth film, his story-telling abilities are sophisticated, his humor dark and slightly sarcastic, and his voyeuristic themes are showing through. "One Round" Jack Sander (Carl Brisson) is a "winner-take-all" boxer at a sideshow carnival. He's undefeated until Bob Corby (Ian Hunter) is attracted to the tent by Sander's pretty fiance (Lillian Hall-Davis) Corby knocks Sanders down (the "round" cards is a clever Hitch bit—the first one is in disrepair and slides into the display easily, but the seldom-used second one looks new and has difficulty going in). Sanders becomes Corby's sparring partner, but seeing how Corby still has eyes for his girl, he works his way up in the standings so he can have one more shot at his rival, inside and outside the ring. Very nice work here, and one starts to realize many minutes in, how few title cards Hitchcock depends on to tell his story. It's all in the images and their details.

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927) "To-night - Golden Curls." The story surrounding the hunt for a London serial killer self-named "The Avenger," (who only kills on Tuesdays and whose victims are always fair-haired), this is the first Hitchcock film considered a "classic" and popular* to be in circulation enough to avoid being lost forever by mis-handling or the vagaries of time. The film was made in Germany (although there is some London location work), and displaying, even at this stage, that Hitchcock was experimenting with story-telling and what could be achieved with moving pictures and graphics. Hitchcock takes pains to use as few dialogue cards (which are usually heavily ironic) and scene-setters as possible. The story is told almost entirely in moving images, even going so far as explain relationships by bits of business—unrequited love is played out with cookie dough and a heart-shaped cookie-cutter. Hitchcock is at full visual realization and his inventiveness with the medium (with a puckish sense of humor) is on full display.

During the murder frenzy with the city on full alert and the population thirsting for revenge (and grisly details on the murders), a young man (Ivor Novello) comes to rent a room from Mr. and Mrs. Bunting (Arthur Chesney, Marie Ault) and his behavior is, to say the least, suspicious: he matches the vague description of "The Avenger" (tall, thin, face mostly covered); he acts nervous and secretive, and leaves the lodgings every Tuesday; he paces constantly; then—most alarming of all—he turns towards the wall every portrait of a blond woman in his room. Yet, he's payed a month in advance, so the Buntings are happy to have him, even when he shows an intense interest in their blond-haired daughter Daisy (June Tripp, but presented as "June"), much to the consternation of her detective suitor, Joe (Malcolm Keen). The motivations of all are complex and hidden, with many twists and turns (often merely provided by the director's manipulations) and the last set-piece of the film—a man-hunt with mob mentality is one of those instances where a feeling of sick helplessness is evoked. The Lodger is the first true "Hitchcock thriller," containing the specific story DNA and peculiar themology, which (when he wasn't distracted by prestige projects or a best-selling adaptation or a particular actress) would be his "fall-back" template lasting his entire career, and is a book-end to his second-to-last film, Frenzy, the movies in between littered with wrong men and women placed in peril by the mistake of their own unexceptionalness.

During the murder frenzy with the city on full alert and the population thirsting for revenge (and grisly details on the murders), a young man (Ivor Novello) comes to rent a room from Mr. and Mrs. Bunting (Arthur Chesney, Marie Ault) and his behavior is, to say the least, suspicious: he matches the vague description of "The Avenger" (tall, thin, face mostly covered); he acts nervous and secretive, and leaves the lodgings every Tuesday; he paces constantly; then—most alarming of all—he turns towards the wall every portrait of a blond woman in his room. Yet, he's payed a month in advance, so the Buntings are happy to have him, even when he shows an intense interest in their blond-haired daughter Daisy (June Tripp, but presented as "June"), much to the consternation of her detective suitor, Joe (Malcolm Keen). The motivations of all are complex and hidden, with many twists and turns (often merely provided by the director's manipulations) and the last set-piece of the film—a man-hunt with mob mentality is one of those instances where a feeling of sick helplessness is evoked. The Lodger is the first true "Hitchcock thriller," containing the specific story DNA and peculiar themology, which (when he wasn't distracted by prestige projects or a best-selling adaptation or a particular actress) would be his "fall-back" template lasting his entire career, and is a book-end to his second-to-last film, Frenzy, the movies in between littered with wrong men and women placed in peril by the mistake of their own unexceptionalness.

Cameo: Hitchcock's first cameo in one of his films, sitting with his back to the camera, at a newsroom desk @03:30.

And Alma Reville, who married Hitch in 1926 and was his "secret weapon" throughout his career (first as continuity person, then as an un-credited editing/story-consultant) has a cameo—the only one she did—as a horrified listener to the news over the "wireless" @05:21.

And Alma Reville, who married Hitch in 1926 and was his "secret weapon" throughout his career (first as continuity person, then as an un-credited editing/story-consultant) has a cameo—the only one she did—as a horrified listener to the news over the "wireless" @05:21.

The Mountain Eagle (1926) This is considered the #1 "lost" film in movie history.

|

| One of the few remaining stills from The Mountain Eagle |

The Pleasure Garden (1925) Second feature by Hitchcock (filmed in Munich) and recently restored from existing pieces. Although filmed in 1925, it wasn't actually released to the movie-going public until after Hitchcock had a hit with his next film, The Lodger. This one is a morality tale of life among chorines at The Palace Garden Theater, known for the "very popular revues" attended by well-heeled lotharios and older gents, who are there for a glimpse of leg and maybe a "chance" at one of the girls. Patsy Brand (Virginia Valli) comes to the big city with the hope of becoming a dancer, but no "in" to meet the owner, Mr. Hamilton. The headliner Jill Cheyne (Carmelita Geraghty) gives her a place to stay—her place—gets her an audition—Patsy's hired—and involves her in her life, meeting her caring fiancee, the responsible company man Hugh Fielding (John Stuart), who is going off to some foreign country for a few months so he can get ahead and marry Jill; and Hugh's friend in the company, Levett (Miles Mander) who is taken with Patsy and starts to pursue her. While Hugh is away, Jill starts to see the rakish Prince Ivan, and Patsy's beside herself trying to convince Jill not to toss aside her fiancee for a life of luxury with the vainglorious Prince. Patsy marries Levett, but learns that her simple dreams of love and life can be undone by distance and the duplicities of those around her. At the same time, she learns a valuable lesson in patience, persistence, and the effects that the absence of each (and alcohol) can lead to disaster and worse.

|

| The very first shot of Hitchcock's existing works— chorus girls descend a vertiginous spiral staircase. Not all of them are blonds. |

Number 13 (1922)-Never completed and presumed lost. A short film (two reels) that was to have starred Ernest Thesiger (The Bride of Frankenstein) and Clare Greet (who became a staple of early Hitchcock films).

|

| A still of of Number 13: Ernest Thesiger and Clare Greet |

With some minimal searching, the Internet has a few complete Hitchcock's from this period available to stream, due to these early Hitchcock's falling into the public domain—there are also a virtual "murder" (the word for a clutch of crows) of rather crude DVD collections of them that are usually presented as if they were all later works by Hitchcock (caveat emptor).

I would also direct your attention to the Hitchcock version of Wikipedia, from there you can find a web-site called the "1000 Pictures Project" reducing every Hitchcock film to 1000 individual frames. Once I found that, I found it incalculably useful for illustrations throughout the text (I believe they follow a mathematical pattern: divide the film's length by 1,000, grab a frame at every interval of that amount. It would explain why some critical shots are not included. But, hey, if you've got a complaint, you try it!). I also spent some enjoyable time re-acquainting myself with "Hitchcock/Truffaut," Francois Truffaut's near-definitive book-length interview with Hitchcock. Want to hear the original tapes of those sessions? Go here. You'll find that the book (translated from English to French and then back to English) doesn't follow the conversation too exactly. And it's many hours of fun listening to Hitchcock tell stories, only occasionally getting annoyed with Truffaut's questions.

Is Hitchcock important to Film or (as he put it) The Cin-e-ma? Of course he is. The man, with every film, designed a new way to present the world, a new way to communicate it—our psychology and our fears made visceral—to turn it into art. He managed to expand the vocabulary of visual presentation, of film itself, into a whole nother realm, and one would think that that expansion stopped dead with Hitchcock, given how often his tricks and framing are used by current directors. Often imitated. Never topped. One is hard-pressed to think of anyone since who has furthered that work as much. The fact that Hitchcock worked in the thriller realm should not negate his importance, though it almost certainly kept him from winning an Oscar for directing...ever (he won the Irving Thalberg Award in 1968). Big deal. He was a name unto himself in Hollywood and throughout the world. Though he may not have had great success at the end, he never stopped being a household word, or being a significant draw for his movies. And that's a result of consistently being innovative in ways of connecting with his audience. And after all, Ingrid, it's only a moo-vie.

The other aspect about Hitchcock to remember is that he was relentlessly entertaining...and just fun.

It would actually spoil things to take Hitchcock too seriously.

Peter Bogdanovich tells the story of interviewing Hitchcock, and after a few drinks, they take the elevator down to have dinner. At the 18th floor, more people come in to go to the dining room, and Hitchcock begins talking, "...Oh, it was horrible! There he was, lying in a pool of his own blood! Blood coming from his ears...from his nose...Blood everywhere!" Bogdanovich has no idea where this is coming from, but assumes that's because he's a little drunk, and must have missed something.

At the 15th floor, more people come in. Hitch continues: " Blood everywhere! He was such a sorry mess, and caked on the walls, it was absolutely horrible, I thought 'I need to go call a doctor, but was there time?'"

The elevator is now at the bottom floor to the dining room and the bell rings, but Hitchcock goes on. "And I said to him, 'What happened? How did this happen?'" The door opens. No one moves. Everyone is waiting to hear the answer. Hitchcock seizes the opportunity to get exit the elevator and get to the dining room first: "Excuse me," says Hitchcock and grabs Bogdanovich and exits the car and goes to dinner, leaving the stunned elevator passengers behind. Bogdanovich turns to Hitchcock, whispering, "Well, what did he say?"

Hitchcock waves him off, "Oh, nothing...that was just my elevator story."

* It was so popular that, when it was remade five years later as a talkie (directed by Maurice Elvey and also starring Novello), it flopped, while the silent version remained in circulation.

** Hitchcock plays this for laughs with a one-armed military funeral attendant, who has to take the phaux-bier down after convincing the attendees and cocking it up.

1 "Hitchcock/Truffaut" copyright 1967 p.54

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment