Walter Murch

Walter MurchWho?

Walter Murch is a film editor, sound editor, film historian and renaissance man. He is part of the "young turks" class of students at USC who changed movies forever--Coppola, Lucas, Milius. Murch directed one movie (the opportunity provided to him by the clout of his class-mates) the weird and wonderful Return to Oz, which followed L. Frank Baum's version of Oz, rather than the MGM Musical Department's (which is probably why few went to see it, and the ones that did were confused and disoriented by it--"Toto, we're really not in Kansas anymore!"). The rest of his career he's been support-staff, but a major supporter whose influence and technique determines the shape and feel of each film he works on.

When I caught up to Murch, he had already done one significant thing--he had coined the phrase that now pervades the sound-editing field, that being "Sound Designer." Briefly, the story of that phrase originates with Murch not being a member of the sound editor's union at the time he was working on Coppola's The Rain People. Coppola asked him how he wanted to be listed in the credits, since they were prohibited from using the "Sound Editor" designation. "Sound Designer" was Murch's reply* And a new aspect and depth to the field was coined. The credit on his next film, George Lucas' THX-1138 had his work classified, not him. "Sound Montage by Walter Murch" (he also co-wrote the screenplay) was how the credits (rolling from the top of the screen against the norm) read. Murch filled the spaces of "THX" with echoing yelps, bizarre clusters of sounds and cheap Muzak. His motorcycles emitted flangeing screams and in plexiglas confessionals deep, sonorous voices gave comfort. His sounds were not only accurate (in that they sounded appropriate to the visuals) but also displayed wit and satire.

His next film for Lucas, American Graffiti, was more sophisticated and tougher to pull off in its more recognizable world. Lucas had strung together a continuous soundtrack of golden oldies and Wolfman Jack patter to serve as a constant back-drop and Greek chorus, and Murch re-recorded the entire track using a method he dubbed "world-izing" (a technique he later found had been used by Orson Welles to authenticate sound). He took the track, played it in a large empty space and recorded the result, moving the speakers at key times to muffle the sound, delay it by a few frames, attenuate it to a thin squeal, or layer on vast coat of echo. He inserted recorded kids' conversations and shrieks to enliven the background, making the empty midnight world of the cruisers full of activity and fun. For Coppola's The Godfather, Murch kept the soundtrack real, but everyone remembers the roar of the el' train as Michael Corleone hesitates in the bathroom of an Italian restaurant before he sets out to "make his bones." There's another favorite sound moment of mine in The Godfather as Michael Corleone walks the deserted echoing halls of the hospital on a visit to see his father. He finds a Christmas party halted in mid-revelry, including a Johnny Fontaine record stuck in a groove and playing one chilling word--"toniiiiihght/toniiiiight." It's unnerving, and the moment we can distinguish what the words are, Michael snaps into action to save his father from a "hit." Murch expanded his role during Coppola's The Conversation, editing the picture as well as the sound, and was responsible for all the sonic permutations that "the conversation" take on. And his other-worldly sound design for Apocalypse Now, took us into the madness and surreal beauty of Viet Nam. Or Coppola's Viet Nam, anyway.

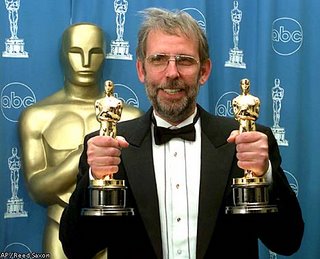

Over the years he's cherry-picked the movies he's supervised: Fred Zinnemann's Julia; three films with Anthony Minghella (The English Patient, The Talented Mr.Ripley, and Cold Mountain) K-19: The Widowmaker, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Ghost, Jarhead for Sam Mendes, Youth without Youth, Francis Coppola's first film in ages.

He's written one book, "In the Blink of an Eye," a practical and philosophical guide to film editing, done numerous interviews and essays (links below) and had two books written about him--"The Conversations" by the author of "The English Patient," Michael Ondaatje and "Behind the Seen," which talks about Murch's efforts to edit "Cold Mountain" using Final Cut Pro, a consumer editing system--and which became a book about Murch, himself. Plus, he's tackled personal assignments, like taking Orson Welles' detailed memo of the steps that could be taken to get "Touch of Evil" back to his original intentions, and then doing just that. Or syncing pioneer film maker W.K.L. Dickson's first attempt at a film-audio hybrid by finally marrying the sound found on a tinfoil cylinder to the original film "reel" both done in 1895. The historic results are here:

When I saw (and heard) THX-1138 on the lower-end of a "Sci-Fi" double bill (with the egregiously pedestrian Soylent Green) at the Crossroads Theater with my brother John, it was a "thunderbolt" moment. No other film I'd seen looked like it, or, more importantly, sounded like it. It was right then that I, more than anything, wanted to be doing that kind of work with sound like that--a "creative" way to bring reality to the screen and color it with a certain sensibility. Not many people get to live their dream. I have. And I'm grateful to Walter Murch for inspiring me--and for continuing to teach me new things with every new film he does.

When I saw (and heard) THX-1138 on the lower-end of a "Sci-Fi" double bill (with the egregiously pedestrian Soylent Green) at the Crossroads Theater with my brother John, it was a "thunderbolt" moment. No other film I'd seen looked like it, or, more importantly, sounded like it. It was right then that I, more than anything, wanted to be doing that kind of work with sound like that--a "creative" way to bring reality to the screen and color it with a certain sensibility. Not many people get to live their dream. I have. And I'm grateful to Walter Murch for inspiring me--and for continuing to teach me new things with every new film he does. We'll be looking at the new film edited by Murch tomorrow: Particle Fever.

Murch articles at FilmSound.Org

Murch articles at Transom. org-Has a great article on Murch's "Rule of 2 1/2 of Sound Mixing"

Murch interviewed on "Fresh Air"

Murch story on "All Things Considered"

Murch as guest on "Studio 360"

Murch on American Graffiti: "Music as Mist"

An interesting little piece on those initial helicopter sounds in "Apocalypse" and a nifty little graphic showing how Murch made it spin through your head.

And finally, Murch explains "Worldizing" far better than I ever could

* Back in my "Bad Animals" studio days, there was a time when "sound designer" was being put on our business cards instead of the usual "engineer." I thought that was a little pretentious, so, being a "smart-ass," I asked that the term "Audio Architect" be put on mine. I've also used the term "Sound-Wave Landscaper," and these days I've boiled it down to "Chief Noisemaker." Now, I'm working at a place where the guy across the hall works on various compression schemes to make mp3's sound good at lower band-widths (so you can stuff more songs into your Ipod) His title? "Audio Architect."

Funny old world, innit?

No comments:

Post a Comment