Gangster Story (Walter Matthau, 1959) An odd one, this. And not a very good one, but still an oddity. A capital "B" B-movie, directed by Walter Matthau, and the only movie he ever directed (someday I want to see the one Cagney directed, too), done very early in his career. At the time, Matthau was a stage actor, but since 1950 he'd been doing small parts in TV series, and didn't make his first film until 1955's The Kentuckian (starring Burt Lancaster and, as we're on a theme here, directed by him, as well) and would start becoming a fixture in films with Elia Kazan's A Face in the Crowd.

It's not known whether it was done on a dare, or out of desperation. The script wasn't much, but Matthau took the job, starring in and directing, because he had gambling debts. His co-star was his wife, Carol Grace, and instead of New York, it was filmed in sunny Los Angeles, mostly during the day, unusual for a supposed film-noir, and where the most shadows are seen in, of all places, a library.

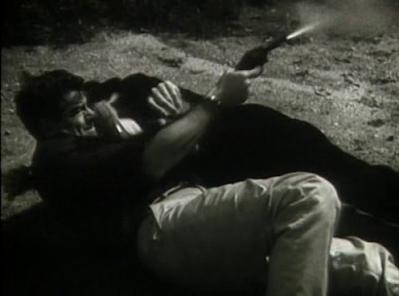

Matthau is fine, his performance, at least, is professional, but loose and schlumpy, and plays well, even in scenes that are patently absurd...like the one where his con character Jack Martin stages a bank-vault robbery by posing as a movie director rehearsing a scene—distracting the guards to "stay in character" and convincing the bank president to open the vault. (Really? It's that easy? Everyone is that dumb and star-struck, not even asking for a filming permit and with no cameras, no crew, nothing?), while most of the other performers range from merely amateurish to a painfully charitable "at least they remembered their lines."

Wouldn't have mattered if they didn't. The entire movie is post-dubbed, the dialogue replaced in the studio after the fact—whether because they had no sound recordist during filming (it was a five-man crew...and edited by future porn director Radley Metzger) or background sounds are so pervasive. It does create a rather unnerving sequence, late in the movie (when nobody was paying attention?) where dialogue is punctuated a few times by the sound of the timing "beep" that alerts the actor when to talk—no one bothered to take them out...it wasn't in the critical first or last reels, and maybe it was just overlooked.

Professionalism aside, what this movie most resembles is the 1973 film Matthau made with director Don Siegel, Charley Varrick, about "the last of the independents" (criminal division). Both Martin and Varrick are bank-robbers, who get caught up in a situation they're not accustomed to: not only avoiding the police, but also the organized crime lord attached to the last institution Matthau's perp robbed. Both involve a good amount of time on the lam and hiding out, although Martin capitulates and, to settle differences, joins the organized bad guys to save his neck. The quirky, nastily-funny Siegel film is full of invention and colorful characters; everything about Gangster Story is pure black-and-white, and is really worth watching only for the curiosity factor. Matthau moved on, and when this vampire of a movie rose from the dead in conversation he'd crack wise in interviews saying the film "premiered at Loew's in Newark and never crossed the Hudson." He never was tempted to direct again.

Professionalism aside, what this movie most resembles is the 1973 film Matthau made with director Don Siegel, Charley Varrick, about "the last of the independents" (criminal division). Both Martin and Varrick are bank-robbers, who get caught up in a situation they're not accustomed to: not only avoiding the police, but also the organized crime lord attached to the last institution Matthau's perp robbed. Both involve a good amount of time on the lam and hiding out, although Martin capitulates and, to settle differences, joins the organized bad guys to save his neck. The quirky, nastily-funny Siegel film is full of invention and colorful characters; everything about Gangster Story is pure black-and-white, and is really worth watching only for the curiosity factor. Matthau moved on, and when this vampire of a movie rose from the dead in conversation he'd crack wise in interviews saying the film "premiered at Loew's in Newark and never crossed the Hudson." He never was tempted to direct again.