or

It Always Pays to Accessorize...

Shaun (Simu Liu), your friendly valet down at that swanky San Francisco hotel is seen by most not to be living up to his potential, and that includes the family of his pal, Katy (Awkwafina), who also valets, and she might agree with them, if she didn't also enjoy the slacker lifestyle and its freedoms.

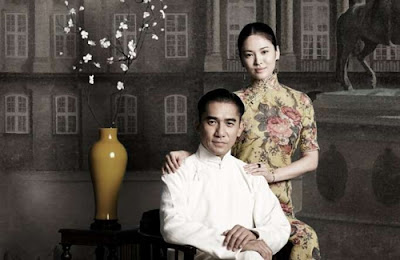

But, they don't know the half of it. Not even the tenth of it. Shaun is actually Shang-Chi, son of the immortal villain Xu Wenwu (Tony Leung, MVP), who, after the death of his mother (Fala Chin) by enemies of his father, was trained as a martial arts assassin to avenge her death. When charged by Wenwu to carry out an assassination, Shang-Chi disappeared, leaving behind his sister Xialing (Meng'er Zhang) and becoming invisible in the world, and leaving behind the world of evil in which his father lives.

All this is to say: tip your valet next time. You don't know what he's been through to get there.

Look. This movie has spent a long time getting made. Marvel was going to do something with "The Ten Rings" as far back as the original Iron Man movie, kind of fluffed the chance when they botched the character of The Mandarin in Iron Man 3—it is alluded to here in this film—and it looks—for now—that they're going to center "Phase 4" of the Marvel films around it (at least until something better comes along).

That's great. One could speculate as to why Marvel chose to go with "The Infinity Stones" story-line in the last phase, but it would be to the detriment of the studio and its perception of their audience. No, let's just say this next step opens up the Marvel Universe to other cultural worlds and can expand their exploration of the Asian culture beyond ninja's and sumurai.

Because, let's face it, the origin of Shang-chi (or "Master of Kung Fu" or "Brother Hand" as he's been known) at Marvel is a little cringe-worthy: unable to obtain the rights to adapt the TV series "Kung Fu" to comics, Stan Lee and the creators at Marvel decided to make their own, snagging the rights to Fu Manchu and creating Shang-Chi as his son. When the "Fu" rights expired, the writers changed the story-line/origin story and allowed the character to mature beyond pulp stereotypes.

The Ten Rings story is an interesting one—not unlike the Infinity Stones, but they're more complex and can do more things,* and it appears that the MCU is making them bracelets as opposed to the comics' finger-rings to make them visually more distinct than the Infinity Gauntlet thing. I'm sure there will be moans from the comics fans that everything isn't completely faithful to the originals, but then, the X-men never wore leather in the comics, either.

So, how's the movie? Pretty good—the first Marvel character movies have traditionally been good to great and then slide into mediocrity (with the exception of the Captain America series, interestingly) although the story is not much to write home about—Delusional Evil Dad wants son back and sends his agents to find him and bring him home. What makes it special is Tony Leung Chiu-Wai is such a great actor that you actually work up some sympathy for him. Plus, Michelle Yeoh is there as "Aunt Nan" (really) and she's always welcome.

Director Cretton keeps things fast and moving, including the dialogue, and as so much of this movie is fighting, he has a great way of filming choreography, which is always a plus in a genre where one should be as expert as possible in animating fisticuffs.

Again, an interesting start for Marvel which makes one excited for things to come.

* And I guess that may be my major complaint about the movie—the Rings aren't explained, they're just a given. They're magic. They do magical things. Why? And how? It tends to negate any sense of tension when there aren't any rules or limitations explained, so that when somebody gets the upper hand you think "Wait! Can he do that?" It's like playing a board game without reading the instructions. There's no meaning to it. It's an adjunct of the visually stunning Marvel comics that had those magnificent ships appearing over a cityscape and having it explained by a character that said "I don't know what it is, but it sure is BIG!"

.jpg)