* I remember, as a kid, having to suffer through Richard's film Summer Holiday, the first film of the double bill, at the Seattle premier of A Hard Day's Night. I have a vague memory of it as being insufferable and more amused at the Beatles-starved audience being impatient with it. Summer Holiday was directed by another up-and-coming director, Peter Yates. It was a hit in Britain, though, earning the position of the 2nd most popular film of 1963, right behind From Russia With Love.

Friday, April 25, 2025

Having a Wild Weekend

* I remember, as a kid, having to suffer through Richard's film Summer Holiday, the first film of the double bill, at the Seattle premier of A Hard Day's Night. I have a vague memory of it as being insufferable and more amused at the Beatles-starved audience being impatient with it. Summer Holiday was directed by another up-and-coming director, Peter Yates. It was a hit in Britain, though, earning the position of the 2nd most popular film of 1963, right behind From Russia With Love.

Friday, August 18, 2023

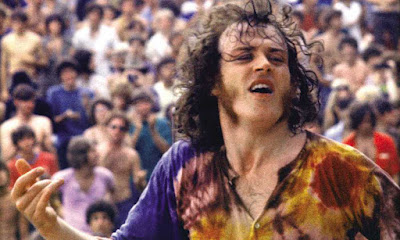

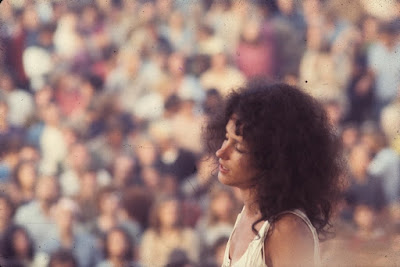

Woodstock

Well, what do you say about Woodstock, the documentary film of the rock festival that made history in the short-lived Summer of Love? That was—what?—54 years ago?

Friday, July 1, 2022

We Are the Thousand

Tuesday, August 24, 2021

Respect

Friday, July 30, 2021

The Wrecking Crew! (2008)

Written at the time of the film's fund-raising campaign at select theaters. After a Kickstarter campaign, the film was released nationally in 2015.

And now, look at that...you can watch it on YouTube for free.

Amazing

Unsung Artists of Note

or

Who the Hell Played It

They're the recording artists you don't know. The hit-makers. The band-members who never got credit. The recording artists who never got royalties. The ones who didn't tour (although some did). The ones who made The Sound.

You could call them The Beach Boys or The Monkees, Phil Spector's Wall of Sound, The Markettes, The T-Bones, The Byrds, The Tijuana Brass, Buffalo Springfield, The Association, The Mamas and the Papas, because they were playing the instruments for the recordings for all those groups.

They're the session musicians who walked in, got the sheet-music and made them sing through their playing, their economy, their versatility, and their incredible talent. Then, they got paid, walked out, and went to their next gig at another studio.

And nobody knows their names. Hal Blaine. Karen Caye. Plas Nelson. Tommy Tedesco. Just a handful of the corps of L.A. session musicians who made the hits and backed the famous and their inimitable recordings. The name that was tossed around in the industry for them was The Wrecking Crew!And the ultimate irony is that their presence in so much music is so pervasive, ever-present, and so essential to the telling of their story that it may make it impossible to see this movie celebrating them. It's a labor of love for the director and instigator, Tedesco's son, Denny, and so it has to be done right, and thus the music has to be there—it (and the interviews that make up the core of the film) cannot be told without it. But each one of those songs costs money to use in the film, and though the piper has been paid, the rights-holders to those songs must be satisfied. And there is so much music, integral to the telling of the tale, to lose anything would be to compromise...and that doesn't seem right for these artists.

The cost is prohibitive, and so Tedesco is raising money through small screenings—one of which I attended the other night—to raise funds to pay off the reproduction, mechanical and distribution rights for the soundtrack to put the show on the road and get it seen...and especially heard. One screening at a time, one of those songs is cemented into the movie and its future, like the parts of an orchestra, the colors, creating a unified whole, the complete story in song.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

It Might Get Loud

What's interesting about the documentary and hearing them three men talk is their completely different approaches to using the electric guitar: for Page, it's technique; for The Edge, it's technology; for White, it's breaking it down to the bare essentials. All three do things nobody else does with the electric guitar, approaching the instrument with a completely different mind-set, as writers approach a piece of paper.

It reduces them to human beings, all capable of greatness, but not fathoming where each gets it ("I can't tell you what a 'process' is" says Page at one point): to see the unbridled love in the eyes of The Edge and White as they watch Page play the opening to "Whole Lotta Love," how Edge intensely scrutinizes White's fingering during a jam session, all three's tales of creative crises—Page's dissatisfaction with studio sessions, Edge's dealing with writing the "War" album, White, how to create a blues aesthetic in a world of "packaged" music and bands.And it is fun to watch them eye each other and tell tales and compare notes, artisans and students all. My favorite moments are with White, whose work I know the least and who always veers precipitously close to the edge of pretension: the first opens the film as he builds a guitar out of scrap wood and a pick-up; the second, is in the extras, and has Page and Edge ask about a particular riff that White wrote for "Seven Nation Army" and White tells the tale of how he socked it away "if I was going to write a James Bond theme song or something." But Edge wants to know how he did it, and when White tells them, the others' eyes go wide with the simplicity of it, and both have to try it. Then, they all riff, finding possibilities. "That'll be five dollars," White cracks.

I'm not a musician, but I appreciate musicianship*, and I have no particular interest in electric guitars, but I like good stories told by good people. And It Might Get Loud sure is fun.

Tuesday, September 17, 2019

Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice

or

"No, I Didn't Re-Invent Myself. I Never Invented Myself to Begin With."

"There Are a Lot of Good Female Singers Around. How Could I Be the Best? Ronstadt's Still Alive"

There's this thing that happens to me. I've worked with Sound for a number of years, so I notice it. I notice my reactions to it. One of those things is when a vocal artist goes from a resting volume to full-throated in a split-second. My heart gives an involuntary jump and tears can come to my eyes. Now, I know you're expecting me to talk about Linda Ronstadt (because that's her on the left), but it's also happened with the late announcer of the Seattle Mariners, Dave Niehaus, who would lull you with talking about how green the grass is in the outfield and the count is 1-2 and SWUNG ON AND BELTED DEEP TO RIGHT FIELD! AND THAT BALL IS GONNA FLY, FLY AWAY....

Instant heart-bump. I remember I heard a call like that while I was listening to highlights of a Mariners season for a potential broadcast introduction, potential because there was discussion that the team was going to move, and I heard one of those "0 to 60" calls Niehaus could do and, realizing I might never hear that again and get that amazing heart-bump again, I started to cry. Silly. But it happened.

So...Linda Ronstadt. Ronstadt does that to me, too. She does that on "You're No Good," starting sultry, then on the third verse ("I learned my lesson, it left a scar...") amping it up so you hear the power in the voice and then going full-bore on the chorus. Heart-bump.

|

| Linda Ronstadt at 16...barefoot. |

Then, she went on to do music from Mexico because she grew up on it, living near the Mexican border in Arizona, and because she respected it enough to "do it right". There were also collaborations with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris, when they formed a mutual admiration society and did a series of albums together. Ronstadt started doing more collaborations with singers she admired because as she says in her new biographical film Linda Ronstadt—The Sound of My Voice: "I was a harmony singer without any material." Plus, she's sold enough records for her backers that they couldn't deny her.

But, how she got there...now that's the story.

It started out with her singing at a very young age in a house that seemed filled with music and the family constantly singing to amuse themselves and because it seemed so natural. Her father had a background of Mexican music and her mother a love for classical. They constantly played standards of the 40's and 50's. Ronstadt was steeped in it and she and her brother and sister started a little singing group that played local clubs, Ronstadt usually appearing on-stage bare-foot. The siblings dropped out, found lives. She stayed and found other collaborators, which became "The Stone Poneys." That lead to a manager who took on the Poneys even though he wanted to fire the guys because he only wanted "the girl singer." Ronstadt wouldn't hear of it, and they had a hit record with Ronstadt's turning of Mike Nesmith's "kiss-off" song "Different Drummer" into a woman's rejection rather than a man's. In the studio, the arrangement was less the Poneys' arrangement and lighter—more feminine, along the lines of Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides Now" which Ronstadt objected to. It became a hit, which Ronstadt ruefully admits "It's a good thing they didn't listen to me."

It started out with her singing at a very young age in a house that seemed filled with music and the family constantly singing to amuse themselves and because it seemed so natural. Her father had a background of Mexican music and her mother a love for classical. They constantly played standards of the 40's and 50's. Ronstadt was steeped in it and she and her brother and sister started a little singing group that played local clubs, Ronstadt usually appearing on-stage bare-foot. The siblings dropped out, found lives. She stayed and found other collaborators, which became "The Stone Poneys." That lead to a manager who took on the Poneys even though he wanted to fire the guys because he only wanted "the girl singer." Ronstadt wouldn't hear of it, and they had a hit record with Ronstadt's turning of Mike Nesmith's "kiss-off" song "Different Drummer" into a woman's rejection rather than a man's. In the studio, the arrangement was less the Poneys' arrangement and lighter—more feminine, along the lines of Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides Now" which Ronstadt objected to. It became a hit, which Ronstadt ruefully admits "It's a good thing they didn't listen to me."The group did break up, however, although one of the band-members stayed with Ronstadt as she was finding her way. You can usually tell Ronstadt from this period because she's wearing one of only three striped dresses she used for gigs. She wasn't interested in being a star, she just wanted to sing. The manipulation to achieve that would come later and from outside parties.

What she found was The Troubadour, which was the place to hang-out if you were interested in the L.A. music scene. It was where Ronstadt hooked up with J.D. Souther, Glenn Frey, and Don Henley, who became band members and then went and formed a little group called "The Eagles." Their first album didn't do very well, but Ronstadt recorded a song from it—"Desperado"—and raised their profile.

|

| Ronstadt on "The Johnny Cash" show with one of those three dresses. |

What Ronstadt was doing wasn't completely definable, although there were many opinions of what kind of singer she was—folk, folk-rock, pop, in an introduction to her appearance of "The Midnight Special," José Feliciano says she's a country singer. The first words of the movie are Johnny Cash's introducing Ronstadt on his show: "Right now, I'd like you to meet a young lady who has what it takes to be around for a long time." But, Ronstadt sang what she wanted to sing, going with what moved her—"Every song has a face I sing to" she would say.

What Ronstadt was doing wasn't completely definable, although there were many opinions of what kind of singer she was—folk, folk-rock, pop, in an introduction to her appearance of "The Midnight Special," José Feliciano says she's a country singer. The first words of the movie are Johnny Cash's introducing Ronstadt on his show: "Right now, I'd like you to meet a young lady who has what it takes to be around for a long time." But, Ronstadt sang what she wanted to sing, going with what moved her—"Every song has a face I sing to" she would say.It didn't hurt that she was cute as a button (still is, by the way), but that had a tendency to make folks overlook the voice and what she was doing with it. The face got her noticed, but as Henley notes in the movie, she gave you the impression that she was "feminine and vulnerable—but when she opened her mouth everything was different." Plus, her eclecticism in material made her tough to pigeon-hole and promote, even as she was also introducing record-buyers to new song-writers and old classics.

But, the formula started paying off with the album "Heart Like a Wheel," which began her collaboration with Asher, the first producer with whom she had no romantic entanglements, and it began a string of best-selling albums that propelled her to the top of the charts and made her a top-draw at stadium-sized concerts.

The documentary, directed by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, was resisted by Ronstadt for years as potentially exploitative and "self-involved," and those instincts aren't there. For those interested in her private life, well, there's some mention of Jerry Brown and J.D. Souther, but that's it. One of The Eagles mentions that he "didn't have a chance," which says more about him and the male-dominated environment Ronstadt was working in, rather than her. There's a lot of archival footage and plenty of heads talking, most importantly Parton and Harris and Karla Bonoff. She blazed a trail, sidestepping relationships, survived what she called "the great culling" of her contemporaries to drugs—her drug of choice was diet pills because...expectations—and instead concentrating on her art and career, and pursuing her muse and her quest for harmony, which led her to championing a lot of songstresses and fellow artists. Blazing a trail? She took a machete to it. And rock...and pop...and country...have gained a lot more soul because of it. And her.

The title is curious, sounding exactly the "self-involved" title that Ronstadt was trying to avoid. But it refers to a Jimmy Webb song Ronstadt covered that plays the end-credits: "Still Within the Sound of My Voice." That might have been a more appropriate title, but a less positive one, evoking the thought that that once powerful voice is "stilled"—Ronstadt confesses she still can hear it in her head, but loss of muscle control makes it impossible to replicate. And although she insists in the documentary that it isn't "singing," she accompanies her nephew on a Spanish song because "it's family."

Heart-bump. Tears.

|

| Linda Ronstadt...now. |