Wednesday, July 24, 2024

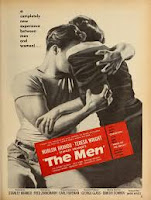

The Men (1950)

Thursday, April 25, 2024

The Formula

Written at the time of the film's release. The Formula (John G. Avildsen, 1980) Fairly lousy movie, done in the clunky Avildsen style, of a police detective (George C. Scott) following a series of murders that involves the MacGuffin of a synthetic substitute for petroleum. Avildsen is the perfect director for thudding cartoons like the "Rocky" series and The Karate Kid. But when having to provide any subtlety or style, as he attempted to do with Slow Dancing in the Big City, it's a miserable failure. And one has to say that he didn't add anything to the thriller or detective genres (or even the "paranoid thrillers" established in the 70's) with The Formula.

The Formula (John G. Avildsen, 1980) Fairly lousy movie, done in the clunky Avildsen style, of a police detective (George C. Scott) following a series of murders that involves the MacGuffin of a synthetic substitute for petroleum. Avildsen is the perfect director for thudding cartoons like the "Rocky" series and The Karate Kid. But when having to provide any subtlety or style, as he attempted to do with Slow Dancing in the Big City, it's a miserable failure. And one has to say that he didn't add anything to the thriller or detective genres (or even the "paranoid thrillers" established in the 70's) with The Formula.

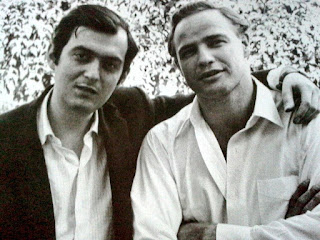

There is one joy, however, and that is to see the meeting of two of the better actors of the American stage square off, and really, it's probably the only reason the film got made (except for a tenuous tie-in to the then-dissolving energy crisis). They have one scene together of any consequence. Both men are a bit over-weight—Marlon Brando playing the fattest of oil-cats—and the two meet for a semi-perfunctory sizing up of each other.* One anticipates sparks flying between two acting titans.

* Come to think of it, Brando's character would have been more effective if he were an insular baron.

** Apparently, the rueful shakes of Scott's head during the scene are his reaction to Brando doing a completely different "read" of his lines than previous takes.

Thursday, April 11, 2024

The Score (2001)

Friday, November 17, 2023

Guys and Dolls

It was one of the "sure things" in a production that spent a lot of its time rolling the dice, hoping for the best.

* Marilyn Monroe lobbied for the part.

Friday, September 6, 2019

Julius Caesar (1953)

Lend me your eyes.

Joe Mankiewicz's first film at his new home at M-G-M was for producer John Houseman, who had produced Orson Welles' acclaimed 1937 stage version of Shakespeare's "The Tragedy of Julius Caesar", staged as if it was a tribal war in Haiti. Welles and Houseman had a venomous falling-out once they both established their film careers, and when Welles started making films of Shakespeare plays (starting with 1948's MacBeth), something might have gotten under Houseman's skin. Perhaps to show him up, Houseman made plans for his own production of "Julius Caesar", with a cast that comprised some of the best film-actors in the world. Mankiewicz adapted the screenplay and then casting began, combining stars from the M-G-M stable and some of the most notable Shakespearean actors of the time.

As well as Marlon Brando.

Now, Brando had made his impression on-stage and on film with "A Streetcar Named Desire," and was the much-ballyhooed klieg-light of "The Method" form of acting, which stood in sharp contrast with the more formal acting of the rest of the troupe, so his casting raised some eyebrows and more than a little skepticism, given his more natural—the term used was "mumbling"—style of acting, especially given his co-stars. After all, co-star John Gielgud was considered a preeminent interpreter of Shakespeare. Brando, knowing what an opportunity he had, prevailed on Gielgud to give him some pointers on negotiating Shakespeare. The rest is pure Brando cunning.

You know the story: "the lean and hungry look;" "It's all greek to me;" Caesar, beware the ides of March;" "Et tu, Brute." Roman emperor Julius Caesar (Louis Calhern) enjoys a popular reign among everyone except some members of the Roman Senate who see the monarch as having too much power and holding onto it for too long, negating any advancement for them, and approaching one of two of Caesar's confidantes—not his military leader Marc Antony (Brando), but the conscientious Senator Marcus Brutus (James Mason)—that the only way they can depose Caesar is to assassinate him.

Several senators confront Caesar and when they can't persuade him to see their way on a specific petition, stab him to death, the previously loyal Brutus being the last to attack and delivering the final, fatal blow.

With Caesar dead, the "liberators" consider the matter of the power vacuum his murder has created (as well as the fear of the populace's reaction to it). To ensure that there is a united front, the conspirators get the stated agreement of Antony to not condemn them when he requests to speak on Caesar's death, assuring that they can make the case for their actions first. It allows a they said/he said with the balance of power at the tipping point.

It's the pivot point on which Shakespeare's play (which is more concerned with the character of Brutus than Caesar) hangs and it is a story of contrasts. Fortunately, Mankiewicz has the right actors to make it play. Mason is all practicality and ideology, making the case for the senators and against Caesar. He lays out his arguments and swings the people to his reasons. But, once Brutus and the conspirators take their leave, Antony brings out Caesar's bloody body and speaks the "Friends, Romans and countrymen" speech, casting himself as the disadvantaged speaker and playing on the crowd's emotions, rather than their reason.

Brando starts out stern and placating, then seemingly breaks down with emotion, building to a feverish pitch and finally screaming the last line, as the crowd starts to rebel against the conspirators (and many of the set's furnishings) and he stands above all and watches the fruits of his handiwork.

With a wedge formed between the conspirators and the people, Antony is free to wage war against them, and, at that point, director Mankiewicz opens up the play out of the studio—Rome is portrayed as bound blocks of marble that have before dominated the film—its own version of a stage's proscenium arch that traditionally frame the Bard's works, to ever so briefly expand the scope by moving out into the real world way from columns and polished surfaces and to Nature's disarray, as the conspirators squabble with each other and their union begins to fray.

It's the best version that I've seen of the play, with strong performances from the entire cast (which also includes Edmond O' Brien, Greer Garson, and Deborah Kerr) and particularly strong performances from Mason and Gielgud, which is where other versions I've seen have fallen a little flat. The roles of Cassius and Brutus are particularly central to the play as it centers on the turning of Brutus to perform an act of betrayal in what he is convinced is a good cause, only to find that it is all for naught and must come to terms with his conscience over it—a sort of "Hamlet" in reverse.

It's an odd combination of star power and acting prowess, and is one of the best presentations of Shakespeare put on the screen.

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

Olde Review: One-Eyed Jacks

This Saturday's films in 130 Kane Are Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks and Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

One-Eyed Jacks (Marlon Brando, 1961)

This one's something of an oddity--it's the only film directed by the greatest "method" actor, Marlon Brando. But what you will see on the screen is really not the film that Brando made. You see, it's one of those stories where nothing really works right. Brando and a number of script-writers worked on the screenplay for a couple of years. Stanley Kubrick was signed to direct and pulled out.* Then, Brando decided to direct it himself and shot a quarter of a million feet of film over a six month period at a cost of five million dollars. Supposedly, there was about 35 hours of film to edit down to a watchable size. Brando's cut was five hours long, but with some noticeable studio shooting, plot summaries were accomplished and got it down to its current two hours and twenty minutes. So it isn't totally Brando's concept.

This one's something of an oddity--it's the only film directed by the greatest "method" actor, Marlon Brando. But what you will see on the screen is really not the film that Brando made. You see, it's one of those stories where nothing really works right. Brando and a number of script-writers worked on the screenplay for a couple of years. Stanley Kubrick was signed to direct and pulled out.* Then, Brando decided to direct it himself and shot a quarter of a million feet of film over a six month period at a cost of five million dollars. Supposedly, there was about 35 hours of film to edit down to a watchable size. Brando's cut was five hours long, but with some noticeable studio shooting, plot summaries were accomplished and got it down to its current two hours and twenty minutes. So it isn't totally Brando's concept.What is there in those two hours and twenty minutes? A superbly acted film, based on a script that at times is intriguing and at times is dull cliche. It's a very weird movie. It's weird, but it does show that Brando certainly had an artistic eye for shots, camera angles, sequences that sometimes take the breath away. You'll also see excellent performances from a cast of Brando, Karl Malden (before TV neutered him),** Katy Jurado, Slim Pickens, Pina Pellicer, Elisha Cook, and Ben Johnson..especially Ben Johnson.

Johnson first worked for John Ford in his westerns and evolved into more than a great actor, but one of those genuine screen presences working in film today. When Johnson and another screen presence, Brando, play off each other in a scene, sparks fly across the screen. Those sparks were expected to fly between Brando and Jack Nicholson in The Missouri Breaks, and never appeared. To see these two greats square off is one of the joys I had watching this film, and also, this film contains my favorite epithet in all of cinema....

They just don't write 'em like they used to."Get up, you scum-suckin' pig!"

Broadcast on KCMU-FM on November 19th and 20th, 1975

Or over-write them. The parts that you can glean from the current cut of One Eyed Jacks (and no one is rushing to restore the full length version, certainly not Paramount Studios, although Criterion did do a restoration for Blu-Ray that was supervised by Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg) suggest an idiosyncratic western with a gritty, grimy feel, which would have made it unique in the western-glut that was happening across theater and television screens across America. Brando's fights were inelegant, and people looked like they got hurt. But the film is a cliche about Authority Figures and Oedipal Conflicts--Karl Malden plays a once-friend-turned-lawman named..."Dad." At one point, Brando's character is whipped in the street before a crowd of on-lookers, and if that doesn't convince you he's a Christ-figure, his tied, outstretched arms just might.

Ulp! It starts to get so thick with things like that, you need hip-waders out in that desert.

** Malden was (at the time of writing this) appearing in an American cop series called "The Streets of San Francisco," with a young actor of good parentage named Michael Douglas.

"Get up, you scum-sucking pig!" occurs at 3:55 in this video—he says it to Ben Johnson