Millions (Danny Boyle, 2004) "The French have said au revoir to the franc, the Germans have said auf

wiedersehen to the mark, and the Portuguese have said...whatever to

their thing."

Millions (Danny Boyle, 2004) "The French have said au revoir to the franc, the Germans have said auf

wiedersehen to the mark, and the Portuguese have said...whatever to

their thing.""Now, it's our turn to say good-bye to sterling. This Christmas, we are going to get the euro. Good-bye, old pounds. Everyone says we're going to miss you."

It's 2002, and with the establishment of the European Union, the country-specific currency in the days of conflicting exchange rates was being replaced by the euro in 12 of the member states (although it's now in 20 of the 27 EU countries) as of the first of that year, all in the name of solidarity and globalization. Such a radical shift is the sort of thing to make great stories of, and this little parable (of a sorts) is a remarkable example of making a great story out of cultural change (and not just the monetary kind).

Director Danny Boyle begins Millions with a sun-dappled intro to a child's world, and a visit to the site of a new housing development, where our hero Damian (Alex Etel) and his brother Anthony (Lewis McGibbon) imagine the building of their soon-to-be new home in fantastical stop-motion animation set to John Murphy's cooing Elfmanesque score.* One is instantly charmed, not only by the fairy-tale way in which the story is introduced, but also by the promise of what is to come. Anything is possible.

But, the sequence is interspersed with shots of impossibly propulsive trains, indicating—along with the house-building sequence that, in this child's world, things can move pretty fast.Once, they've moved into their new home named appropriately "Serendipity" ("Surprisingly spacious with attractive views!" enthuses Anthony), it's off to school with them, where Anthony is better able to adapt than Damian who when he's asked if he has any heroes rattles off the names of saints (with whom he's obsessed) enthusiastically detailing their grisly fates to the horror of his fellow students (whose heroes are footballers).But, their lives change when Damian imagines an audience with Clare of Assisi (1194 to 1253 and the patron saint of television...no, really) in his hermitage made of moving boxes taped together to form an ornate structure and its interrupted by the construction being crushed by a flying Nike bag filled with pound notes—£229,520 to be precise—which Damian assumes (naturally) that it came from God. His brother, Anthony, is far less deistic and thinks—maybe—it came from a passing train, but doesn't question it enough to see the opportunities implied. The kids stash the loot, vow to not tell their Dad, and Anthony begins to use it to gain friends at their new school to form a "posse."But, Damian has other ideas (of course). Since the funds came from God, he starts to distribute it the way his idols, the saints, would. His first act is to buy a bunch of pigeons and release them, as per St. Francis (who dutifully shows up to give his approval and suggest that Damian use the money to help the poor). With aid from St. Nicholas, he leaves stuffs a lot of pound notes into the mail-slot of some neighboring Mormon missionaries (they needed a dish-washer and a microwave), the Ugandan Martyrs persuade Damian to give to a Christian charity that will provide wells to African villages (that one is so obvious and un-anonymous it gets him in trouble with his whole family and exposes the fact that he has the loot), then St. Peter comes by for a visit and tells him maybe he should slow down a little as miracles aren't always what they seem.

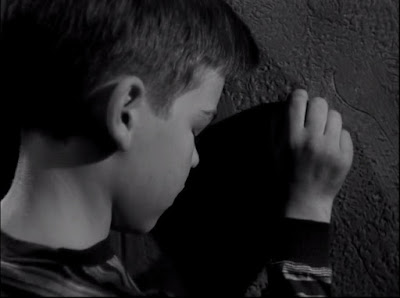

Damian with St. Francis (note the halo)

Meanwhile, there's all this money with a certifiable expiration date and two boys have to figure out how to use it while it's still valuable. Anthony starts to tour real estate "for investment opportunity." Damian comes to realize that even though giving to the poor is a really good idea "it's really hard" to do. Plus things get...complicated once Da knows there's all this money and then, there's the business of some guy nosing around the neighborhood looking like he's lost something really valuable. And Doyle maintains his penchant for keeping things visually fascinating and telling a story in unconventional ways, but still conveying what he absolutely means. Millions is one of those ones I missed in the theater, and one I deeply regret for having missed it. It's a little gem of a movie Boyle made between his zombie-film 28 Days Later (which will be getting a sequel this year) and his sci-fi film Sunshine but sweeter than his usual fare, although—Doyle being Doyle—it does flirt with some dark material involving child jeopardy, but it ultimately has its sacred heart in the right place.At one point St. Peter tells Damian: "Something that looks like a miracle turns out to be dead simple." Millions isn't dead simple, but it is something of a miracle.

It's a highly charming

movie, while avoiding the usual cute kid cliches, and maintaining a

quite sophisticated tone of drama and off-the-wall comedy. That was a

trick even Disney found hard to pull off.** It gets a very high

recommendation from me.

* I was delighted to see that the score was performed by the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and The Northwest Boychoir and recorded at Studio X of my old stomping ground Bad Animals and recorded by old comrade Reed Ruddy. Nifty!

** This being what they are, and the film being originally produced by Fox Searchlight, it is now the property of The House of Mouse.

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.jpg)

_6.png)