I don't like those: they're rather arbitrary; they pit films against each other, and there's always one or two that should be on the list that aren't because something better shoved it down the trash-bin.

So, I came up with this: "Anytime" Movies.

Anytime Movies are the movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, sometimes it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again (and again!) and never tire of them. There are ten (kinda). They're not in any particular order, but the #1 movie IS the #1 movie.

It's amazing what movies aren’t on the list. It’s amazing to me, and I made the list! Dr. Strangelove isn’t here because 2001 is. A lot of defacto “classics” aren’t here. Where’s Casablanca? (Love it!) Where’s Star Wars? (Love that!) Where’s The Godfather? (Love…and respect...that!).

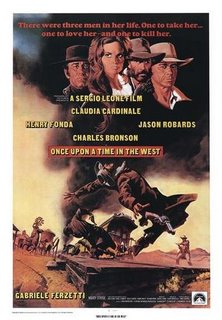

THX-1138 was a big influence. Not here. Where’s Gone with the Wind? (Easy. I hate Gone with the Wind, though I’ve seen it five times) There’s no Hitchcock (That’s interesting). No Spielberg (ditto). The Wizard of Oz? (Not here...not in Kansas, either!) No superhero movies (Not so surprising, really). No foreign films. Hmmm. Seven Samurai and Yojimbo (natch!)—but more importantly, my favorite Kurosawa (so far), Ikiru—and The Leopard, Black Narcissus, Sounder, and Nights of Cabiria would have made the list, but my history with them is short, and I didn’t feel I could write about them well, so, no…unless you count Once Upon a Time in the West and it’s so influenced by American westerns, I don’t really consider it a foreign film.

I think The Wild Bunch and Silverado I consider perfect screenplays. But they're not here. There’s a lot of John Ford films I love dearly along with many directed by Howard Hawks. Those gentlemen get a delegate apiece. It’s a Wonderful Life—but not as wonderful as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. And then there are the missing persons: Where’s Bogart? Cagney? Hepburn (either of them)? Stanwyck? Patton, Lawrence of Arabia, Willy Wonka. Hey, no musicals, though I think Singin’ in the Rain is a near-perfect film. And Goldfinger? Yeah, yeah, I know. It’s a peccadillo, but it's also my list. Go make your own.

And I hate to say it, but I must acknowledge it—the list is so "male"-oriented...and so white (To Kill a Mockingbird with it's white paternalism SO doesn't count...). As Roger Ebert used to crib from Robert Warshow: "A man goes to the movies. The critic must be honest enough to admit that he is that man." This list lays out pretty flatly that i'm a white male...and American.

There were some interesting coincidences, Two films set in Monument Valley (and it makes a cameo in a third). Two with Jean Arthur (and Thomas Mitchell). Three (four, actually) about “lost causes.” All different genres. Different decades.

The other thing is I called them “Anytime Movies”—not the typical “desert island discs,” (or, more appropriately for what they are, "OCD Movies"). On that subject, I think I’d want a desert island movie like a Time/Warner handyman film on “How to Build a Boat” or “25 Interesting Recipes You can Make Using Sand,” or that “Gilligan’s Island” episode where the Professor makes a radio out of a cocoanut.

And none of these movies contain my favorite moment(s) in film. That one is pretty obscure.

It’s the last fourteen minutes or so of Francois Truffaut’s Farenheit 451. The combination of Ray Bradbury’s ideas (a literal translation of RB is usually problematic), Truffaut’s screenplay and direction, and Bernard Herrmann’s yearning music make the most sublime moments of film I’ve ever loved. It’s the “Book People” sequence, where Montag (Oskar Werner), the Fireman who has rebelled against the repressive textless society and escaped never again to burn books (well, except for one) makes his way out of the city to a fragile wooded area (by a lake) and finds a village of people who have each committed to memory one beloved book. As fall turns to winter, these people walk and recite their treasures. One little vignette has a little boy being taught a book by a man, dying, and in a fade, it is the boy who recites by himself, and there is a moment…a moment…when he can’t remember. If that kid loses the book…it’s gone.

That moment has always chilled me right down to the bone far more than any horror movie could, because it shows the fragility of an idea…as fragile as a life. Maybe it’s the sense that those books will go on, life after life. Maybe its because these people have taken on one sacred thing to devote their life to, like monks of literature. Maybe because it’s an island of sanity in a world of madness. Maybe because it’s the perfect melding of picture and sound. But the cumulative effect makes me want to check in with the sequence every couple of months. To make it easy for me, here it is:

Now, once again, for the last time, here are my “Anytime Movies.”

There were some interesting coincidences, Two films set in Monument Valley (and it makes a cameo in a third). Two with Jean Arthur (and Thomas Mitchell). Three (four, actually) about “lost causes.” All different genres. Different decades.

The other thing is I called them “Anytime Movies”—not the typical “desert island discs,” (or, more appropriately for what they are, "OCD Movies"). On that subject, I think I’d want a desert island movie like a Time/Warner handyman film on “How to Build a Boat” or “25 Interesting Recipes You can Make Using Sand,” or that “Gilligan’s Island” episode where the Professor makes a radio out of a cocoanut.

And none of these movies contain my favorite moment(s) in film. That one is pretty obscure.

It’s the last fourteen minutes or so of Francois Truffaut’s Farenheit 451. The combination of Ray Bradbury’s ideas (a literal translation of RB is usually problematic), Truffaut’s screenplay and direction, and Bernard Herrmann’s yearning music make the most sublime moments of film I’ve ever loved. It’s the “Book People” sequence, where Montag (Oskar Werner), the Fireman who has rebelled against the repressive textless society and escaped never again to burn books (well, except for one) makes his way out of the city to a fragile wooded area (by a lake) and finds a village of people who have each committed to memory one beloved book. As fall turns to winter, these people walk and recite their treasures. One little vignette has a little boy being taught a book by a man, dying, and in a fade, it is the boy who recites by himself, and there is a moment…a moment…when he can’t remember. If that kid loses the book…it’s gone.

That moment has always chilled me right down to the bone far more than any horror movie could, because it shows the fragility of an idea…as fragile as a life. Maybe it’s the sense that those books will go on, life after life. Maybe its because these people have taken on one sacred thing to devote their life to, like monks of literature. Maybe because it’s an island of sanity in a world of madness. Maybe because it’s the perfect melding of picture and sound. But the cumulative effect makes me want to check in with the sequence every couple of months. To make it easy for me, here it is:

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Citizen Kane (1941)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

—Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

The Searchers (1956)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Chinatown (1974)

American Graffiti (1973)

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Goldfinger (1964)

Bonus: Edge of Darkness (1985)

Citizen Kane (1941)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

—Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

The Searchers (1956)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Chinatown (1974)

American Graffiti (1973)

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Goldfinger (1964)

Bonus: Edge of Darkness (1985)

.jpg)