First things first, Barrymore is great, looking the very image of Holmes as seen in the original Sidney Paget drawings that accompanied the first publication of the cases in The Strand Magazine. His Holmes is cunning, contemplative and very rarely wears a deerstalker. The story presents a complicated tale (actually several mysteries in one) spanning years of evil deeds perpetrated by Holmes' nemesis, Professor Moriarty (played by an actor with the wonderful name of Gustav von Seyffertitz) on the more young, innocent members of British society (including a young William Powell—this was his first film). It's up to Holmes (and to a much lesser extent, Roland Young's Watson) to get to the bottom of the case.

|

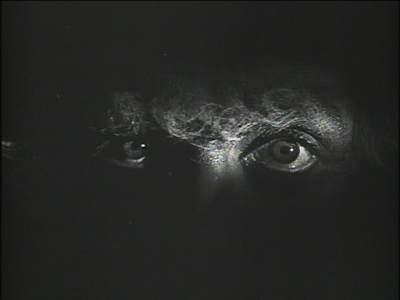

| Powell and Barrymore in the '22 Sherlock Holmes |

It's a silent film, the particulars told in title cards, which is problematic as Holmes, once coerced to reveal the methodology of his deductions, can be a verbose creature. So it falls on the title card authors to show the process in a kind of dense short-hand. Those moments are few and far between. Mostly, it's standard melodramatic fare, without the Doyle back-stories that tie everything together, and explain the gears that set the whole thing in motion (This is done at the beginning and inserting Holmes into it). It's all pretty surface-stuff, befitting a stage presentation (although Parker manages to cross the Victorian era and motor car era in his production design), with Barrymore's performance—he was 40 at the time— breaking the silent tradition by being more interior, more cerebral, setting Holmes' detective apart from the usual over-emoting that was the tradition and chief weapon in communicating emotions during the silents.

Granada's Holmes, Jeremy Brett, used to talk about a conversation he'd had with Robert Stephens, who played the role in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, where Stephens commented "There's nothing there inside the character, just a big empty space that you must fill any way you can." Essentially, he's right. There are lots of Sherlock's who are bland and impenetrable—in fact, the BBC had a rough time with a revolving door of actors who couldn't live up to Brett's version, even when the actor was deathly ill, and didn't until the character was revamped in modern times and played by Benedict Cumberbatch. A "silent" Holmes makes the portrayal even tougher to pull off, as Holmes' theatricality is easiest portrayed with his voice and phrasings, weapons not available in silent films. But Barrymore still manages to make a memorable Holmes, if slightly diluted by a tendency to become romantically involved with his clients. Gillette did so in his play to win audiences and make Holmes a more romantic hero. And although it's slightly unnerving to see, Barrymore makes it acceptable.

Next Saturday: The elementary Sherlock Holmes.