Blame the confusion—all of it—on Joseph McCarthy (and put his minion, Roy Cohn, as an asterisk).

Losey (and Dassin) were caught up in the Communist hunt in the 1950's and left America to work—and wait for things to calm down and the industry "black-list" to be officially/unofficially ignored.

As for The Boy With Green Hair, it's not a bad start for a first film; I've been working on a post for one of Fred Zinnemann's early films, My Brother Talks to Horses, which is just plain weird, but one has to start somewhere.

There was a boy

A very strange, enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far

Very far, over land and sea

A little shy and sad of eye

But very wise was he

"Nature Boy" words and music by eden ahbez

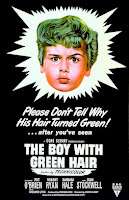

Police find a silent and bald child (Dean Stockwell—he was 12) wandering the streets and bring him, calling on Dr. Evans (Robert Ryan) to find out what the situation is. Through coaxing—and some food—Evans learns that the boy's name is Peter Frye, that his parents are missing and have been since travelling to London during the second World War. The small Frye has been traded from relative to relative until being taken in by Gramps (Pat O'Brien), a retired vaudevillian who, it turns out, is not really his grandfather. Despite the lack of blood-ties, Peter found a stable life with the old man, who is genial and caring and has a boy's sense of play and wonder.Peter has settled enough to be regularly attending a school, with its clique-mindedness and "new-kid" insecurities, and though he makes friends, there's also others who make school-life testing beyond what might be on a page. Much is made that Frye doesn't have any parents—any "real" parents, like a "normal" kid would have—and it becomes apparent (once others bring it up) that he might be considered a war orphan (as his class is setting up a collection at school for the European kid-survivors. This gets to young Peter and more and more, his thoughts turn to the war and its consequences on people...people like him. It doesn't help that there is much in the news about civil defense and the escalating tensions of nuclear proliferation. "Duck and Cover" sounds like a good idea until the shock-wave comes along. It puts a lot on Peter's mind about the consequences of the last war and the likely next one.

So, imagine the kid's surprise when he wakes up from one troubled night's sleep with GREEN hair! At first, he thinks it's funny—what a goofy thing to have green hair. Gramps is alarmed, but goes along with it. But, the kids at school—they consider Peter a freak and begin to regularly haze him and try to cut his hair off—him with his pacifist ideas and all. The fascists! And if they weren't bad enough, the parents are equally aghast. A BOY with green hair! What WILL happen to the neighborhood? And despite being a good-natured soul, Gramps feels the public pressure about this kid that stands out, and Gramps takes him to the barber to get his head completely shaved. A crew-cut wouldn't be good enough, not even in the 1950's.

|

| A vision of European war-orphans explain it all to Peter. |

One other interesting aspect of the film is its score—by Leigh Harline—making extensive use of one of the Summer of '48's music hits, "Nature Boy," a strange and haunting song that almost literally fell into Nat King Cole's lap. It lends the movie a touch of the exotic that makes it a bit more credible...and heartfelt.

And then one day

One magic day he passed my way

While we spoke of many things

Fools and Kings

This he said to me:

"The greatest thing you'll ever learn

Is just to love and be loved in return"

.jpg)

.jpg)