I don't like those: they're rather arbitrary; they pit films against each other, and there's always one or two that should be on the list that aren't because something better shoved it down the trash-bin.

So, I came up with this: "Anytime" Movies.

Anytime Movies are the movies I can watch anytime, anywhere. If I see a second of it, I can identify it. If it shows up on television, my attention is focused on it until the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the direction, sometimes it’s the writing, sometimes it’s the acting, sometimes it’s just the idea behind it, but these are the movies I can watch again and again (and again!) and never tire of them. There are ten (kinda). They're not in any particular order, but the #1 movie IS the #1 movie.

Landscapes.

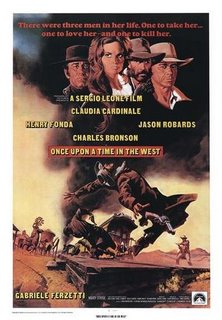

Landscapes.That’s what’s featured in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. Whether it’s the vast, aboriginal spaces of Monument Valley—an affectionate genuflection to the films of John Ford—or the intricately chiseled planes of the faces of Charles Bronson and Henry Fonda—you spend a lot of time looking at both in Once….—as well as deep close-ups of the faces of Jason Robards and Claudia Cardinale. There is one shot where Bronson ever so slowly relaxes a smile out of existence. Bronson does it so subtly you don’t know what’s happening until it’s happened. It’s one of the things I look forward to in the Dance of Death of Once Upon a Time in the West. Here are some others:

1. “Looks Like We’re Shy One Horse…” The first twelve minutes. A dilapidated train station in the middle of nowhere. Three long-coated bad-men wait for a train. They while away the time, each in their own unique fashion. Driven mostly by sound and filmed in extreme close-ups, the sequence, accompanied by the homely squeak of a windmill—one of the out-sized sound effects typical of Leone’s westerns—and the jokey placement of the credits, rolls on and on until a confrontation ends explosively. It’s an opening of great economy and intricate film-making. Few words are spoken throughout. I’ve shown students this sequence to show just how much presence and atmosphere simple sound effects can bring to a scene. It’s just the opening gambit in a plot by two men who are playing against each other. It will take the entire movie to explain why.

3. “People Scare Easier When They’re Dyin’” The villain of the piece is the meanest, rottenest most conniving scumbag to ever walk a dusty street and spit on it. “Frank” is a sadist who smiles when he kills and for the first time in his life he has a patron with a vision—one big enough for Frank to start to see how there might be such a thing as a future, and that one man can own it. He just can’t understand why people are getting in his way.

4. “Instead of Talking, He Plays. And When He Better Play, He Talks.” The composer and the director did it backwards. Ennio Morricone wrote the music for the film first and Leone built his sequences around the music, playing it on-set to establish mood. There are two spectacular pay-offs--one in the previously mentioned Monument Valley sequence. But the other is at a train station where Claudia Cardinale, has just arrived from New Orleans to find no one to meet her. After a long wait (which is actually mercifully short for a Leone western) she decides to hire passage. Sounds disappear as she is seen through a station window talking to an official, and then the camera HEAVES up and over the roof, and in a burst of music reveals a burgeoning western town full of life and activity. It’s as if all of America is presented in that one astounding crane shot. My wife audibly gasped when she saw the shot in some movie clip program on TV, so stunning is the effect. And more than a little of the power of that shot is due to Morricone’s music and the angelic voice of Edda Dell’Orso, wordlessly cooing an ode to the country and to the protagonist around whom the movie and the future hinges.

3. “People Scare Easier When They’re Dyin’” The villain of the piece is the meanest, rottenest most conniving scumbag to ever walk a dusty street and spit on it. “Frank” is a sadist who smiles when he kills and for the first time in his life he has a patron with a vision—one big enough for Frank to start to see how there might be such a thing as a future, and that one man can own it. He just can’t understand why people are getting in his way.

4. “Instead of Talking, He Plays. And When He Better Play, He Talks.” The composer and the director did it backwards. Ennio Morricone wrote the music for the film first and Leone built his sequences around the music, playing it on-set to establish mood. There are two spectacular pay-offs--one in the previously mentioned Monument Valley sequence. But the other is at a train station where Claudia Cardinale, has just arrived from New Orleans to find no one to meet her. After a long wait (which is actually mercifully short for a Leone western) she decides to hire passage. Sounds disappear as she is seen through a station window talking to an official, and then the camera HEAVES up and over the roof, and in a burst of music reveals a burgeoning western town full of life and activity. It’s as if all of America is presented in that one astounding crane shot. My wife audibly gasped when she saw the shot in some movie clip program on TV, so stunning is the effect. And more than a little of the power of that shot is due to Morricone’s music and the angelic voice of Edda Dell’Orso, wordlessly cooing an ode to the country and to the protagonist around whom the movie and the future hinges.5. “Ma’am, It Seems To Me You Ain’t Caught The Idea” For the first time in a Leone western, a woman is the hero, but like her predecessor—"The Man with No Name"—she is flawed and has some learning to do, and it’s up to Leone’s trio of men – another man with no name (going under the aliases of dead men), a wolf-like vagabond-thief, and the villain, Frank—to push, prod, blackmail, challenge and coerce her into a new role. It’s a role each man knows they’ll have no part of, and that, for a time, she is reluctant to fulfill. In the last shot of the film, she is seen bringing water to the railroad work-crew who will be bringing people and prosperity to what will be her town. It may seem a servile role, but as we pull away and follow the disappearing tracks to the frontier, leaving her to her future, she begins to bark orders, to direct and take charge. Her station will become a cornerstone of the push west. “This movie drips with testosterone,” a colleague once told me after a screening. Yes, but Leone includes a healthy shot of estrogen as, for the first time, he is dealing with a story that not only leaves the past behind, but also looks forward to the future. After his spectacular success with the "Dollars" trilogy starring Clint Eastwood, Leone was given a lot of money, quite a bit of it from Paramount Pictures, to not make his next planned film (based on the novel, "The Hoods" which would eventually become his last film Once Upon a Time in America) but make his next production a western. When he delivered this slow-moving epic on a small scale writ large, the full length film (2 hours, 46 minutes) became a hit in Europe, but Paramount cut what it considered "extraneous" material—a full 25 minutes of it—for its American release.* The film was a bomb in the States. It was released, after all, in 1968, the year of Bullitt, Rosemary's Baby, and 2001: a Space Odyssey. Cinema, and its audience, was changing. The next year Easy Rider would be a huge hit. Once Upon a Time in the West might have seemed a little archaic to the youth audience. Eastwood, a popular star outside of the Leone films by then, wasn't in it. Bronson—popular in Europe, but a supporting actor in America—was. Fonda, Cardinale, and Robards, perfectly cast though they are, did not bring in droves of film-goers.

But, despite its reputation from the box-office performance upon its release in America, the film has developed a cult following here—more than that, it is acknowledged as a masterpiece of film-making, one of the great films of the 20th Century, maybe a little behind-the-times for the box-office, but certainly ahead of its time for the influence it has had on subsequent film-makers.

For me, it is simply beautiful, dusty and hard-scrabble though it is. Some of the images, some of the sequences, run through my head daily, and Morricone's music "ear-worms" into my head once a week. It is still, despite the acolyte-directors who "one-off" the style and sometimes the film, wholly original, while acknowledging its debt to films of the past, presenting them in its own unique way. You'll never see a wide-screen film filled so interestingly as Once Upon a Time in the West. Filled and brimming. Rustic and operatic, Once Upon a Time in the West is a fairy-tale of Myth and History—film history—while making its own.

Claudia Cardinale: The West wrapped around her little finger.

Anytime Movies:

Once Upon a Time in the West

-Only Angels Have Wings

The Searchers

** There had been a precedent: United Artists cut 16 minutes from the nearly 3 hour The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly. And Paramount made a worse decision when it eventually released Leone's Once Upon a Time in America: restructuring the director's intricate flashback structure into a chronological narrative, which robbed the movie of its melancholy tone, and removed any mystery the film contained. Curiously, the longer film is fascinating throughout, but Paramount's re-edit seemed interminable. It just shows the differences between a genuine film-maker and studio hacks.

The Searchers

* And, on Sunday, we'll put up a "Don't Make a Scene" feature from each week's film.