Seven Chances is a few films in one: it starts with a brief prologue in tableau'd fades of a stalled romance between Jimmy Shannon (Keaton) and Mary Jones (Ruth Dwyer) as they don't communicate as the seasons change around them, and Mary's puppy becomes a full-grown dog.*

Then, the plot thickens. A financial broker on the verge of bankruptcy, he is informed that his grandfather has bequeathed him seven millions of dollars on one condition—he must be married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday (which happens to be that day). His first instinct is to marry Mary, but circumstances force him to look elsewhere, and he spends the day trying desperately to get married, but is refused at every drop to his knees.

Next, an ad is placed in the paper for a bride, which produces an entire church-load of potentials, which, once panic ensues, begins a long drawn out chase, first through the streets of 20's Los Angeles (in scenes highly reminiscent of Keaton's 1922 short Cops, but with the added joke of runners in white dresses and long veils). As is typical with Keaton, the ideas build, usually logically from barriers and obstructions and passers-by thrown into the mix, the silent equivalent of a parkour course which the dexterous (and seemingly boneless) Keaton must dodge, duck and dance around while scampering at full tilt.

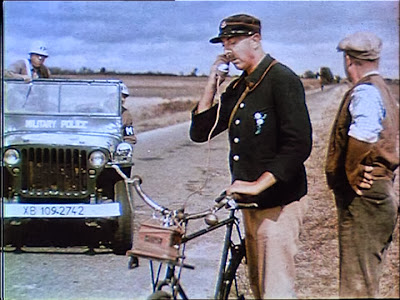

But, once out of the city limits, Nature starts to come into play with expected and unexpected obstacles that keep piling on, literally, in an extended sequence where Keaton, running down an impossibly long hill, must avoid an avalanche of boulders, that seem bent on pushing him around. The sequence came out of a preview, where a scene of a flopping Keaton dislodging some rocks, start following him down hill, which he quickly tries to avoid. The shot garnered the biggest laugh of the preview, so Keaton went back and shot some more footage and built another routine out of it, building, building, building, extending the momentum, and the resulting audience reaction until he was satisfied.

There are a couple of brief un-PC moments (one of which will fly by modern audiences, but it involves the mentioning of a '20's female impersonator), and there's just a whiff of misogyny here—a mob of women is still a mob, though—but, then part of the joke is that if Jimmy can't have "his" girl, any girl will do, but it's belied by all of the "any" girls rejecting him outright. Also of interest is a brief peak at a young Jean Arthur in the role of a country club receptionist.

Anything involving Keaton on-screen is worth seeing, and good for quite a few laughs...when one isn't gaping in wonderment of what the man was capable of, and capable of doing.

Then, the plot thickens. A financial broker on the verge of bankruptcy, he is informed that his grandfather has bequeathed him seven millions of dollars on one condition—he must be married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday (which happens to be that day). His first instinct is to marry Mary, but circumstances force him to look elsewhere, and he spends the day trying desperately to get married, but is refused at every drop to his knees.

Next, an ad is placed in the paper for a bride, which produces an entire church-load of potentials, which, once panic ensues, begins a long drawn out chase, first through the streets of 20's Los Angeles (in scenes highly reminiscent of Keaton's 1922 short Cops, but with the added joke of runners in white dresses and long veils). As is typical with Keaton, the ideas build, usually logically from barriers and obstructions and passers-by thrown into the mix, the silent equivalent of a parkour course which the dexterous (and seemingly boneless) Keaton must dodge, duck and dance around while scampering at full tilt.

|

| Of course, there must be a chase... |

There are a couple of brief un-PC moments (one of which will fly by modern audiences, but it involves the mentioning of a '20's female impersonator), and there's just a whiff of misogyny here—a mob of women is still a mob, though—but, then part of the joke is that if Jimmy can't have "his" girl, any girl will do, but it's belied by all of the "any" girls rejecting him outright. Also of interest is a brief peak at a young Jean Arthur in the role of a country club receptionist.

Anything involving Keaton on-screen is worth seeing, and good for quite a few laughs...when one isn't gaping in wonderment of what the man was capable of, and capable of doing.

The country portion of the Seven Chances chase scene.

The scene at :30 inspired the extended avalanche scene.

* And it's shot in the primitive version of Technicolor!