Interviewer: What do you think about the kids?

Police Officer:

From what I've heard from the outside sources for many years I was

very, very much surprised and I'm very happy to say we think the people

of this country should be proud of these kids, not withstanding the way

they dress or the way they wear their hair, that's their own personal

business; but their, their inner workings, their inner selves, their,

their self-demeanour cannot be questioned; they can't be questioned as

good American citizens.

Well, what do you say about Woodstock, the documentary film of the rock festival that made history in the short-lived Summer of Love? That was—what?—54 years ago?

Chaotic, but, as such, it was true to its subject.

As with most documentaries, "it is what it is." But—even though it is a documentary—it is, as such, subject to a narrative thrust that is imposed in the editing phase, which was daunting. Look at the statistics: There were 14 to 18 cameras filming it over three days, under strenuous conditions, night-shots, in the rain and mud, by camera-men with very little sleep, who would circle the acts like gladiators, sometimes catching each other in the frames, at angles looking up at the performers, meaning they were on their knees or hunched, trying to maintain their positions and their angles. They brought back 50 miles of film—one hundred and twenty hours of exposed film. Just to watch all of it took two weeks, even before editing started.

"Somebody was saying this is the second largest city in New York. There's

been no police. There's been no trouble. If you check the statistics

out, you'll find out these people at three hundred plus thousand people

have lived together peacefully."

Then, they had to sync picture to sound, and picture to picture—opposing angles from different sources had to match frame or it would destroy the illusion of watching a performance in real-time. Then, they had to make sense of it all, not just the performances, which would be the "draw" for the audience, but also those in attendance, which was the biggest story (so many people—400,000—crammed into such a small space, experiencing—only a couple thousand could actually see the acts, most just getting the sound, usually at a distance). The crews that built the stage, lit the stage, cleaned the stage, in rain or sun. The massive undertaking to get people on the stage to entertain a small city. Interviews with townsfolk who looked at the spectacle and supposed it was a disaster or a triumph, even the local merchants, who pitched in to feed the overflow crowd.

All were photographed dutifully, painfully. And at a Warner Brothers-stipulated running time of 3 hours, the editors had to cull the highlights, choosing to put as much footage as possible on the screen, choosing a three-screens-in-one widescreen presentation, that, in certain moments becomes phantasmagorical.*

Under Wadleigh's supervision, the editing team led by Martin Scorsese and his editor Thelma Schoonmaker (with an uncredited assist from Walter Murch and a squadron of other editors) began to shape a story out of the chaos, that, in its long-form, captures a moment in a declared state of emergency where the music was really good, and the crowd was appreciative and "made do."

Two people died at Woodstock. Two were born. Statistically, that makes for a zero population growth, one of the many societal concerns at the time. There was also a war going on, which was ridiculed and mocked by the performers on-stage, but when the U.S. Army started supplying helicopters to transfer sick, injured and overdosed to nearby hospitals, their efforts were lauded from the stage ("Somebody may have noticed or all of you may have noticed, our familiar

colored helicopter over there. The United States Army has lent us some

medical teams and giving us a hand. They're with us, man! They are not

against us! They're with us and they're here to give us all a hand and

help us."). Survival was the order of the day. Survival with some of the best musical acts extant.

Here's who appears in the film:

Richie Havens—an intense set of "Handsome Johnny" and "Freedom"/"Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child." Havens was the first artist to perform, even though he was scheduled to be fifth. But, the opening act was Sweetwater, was stuck in traffic—so was Havens' bass player, for that matter—and Havens reluctantly took the stage, telling promoter Michael Lang that he would owe him big-time if the crowd threw bottles at him. He needn't have worried. Havens' set went on for nearly an hour, including three encores—the third, an entirely impromptu song he made up on the spot, "Freedom." Havens would joke that he had to go see the movie to write down what it was he actually sang!

Canned Heat—the Director's Cut contains one song—"A Change is gonna Come" from their one hour set, although their hit "Goin' Up the Country" is played over the opening credits.

Joan Baez—although six months pregnant at the time of the concert, and with her husband in prison, Baez performs "Joe Hill" and "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" in the film.

The Who—in what may be the longest sequence in the film, play "We're Not Going to Take it" and "See Me, Feel Me" from the concept album/opera "Tommy" and "Summertime Blues."

Sha-Na-Na—the classic oldies rock group play "At the Hop."

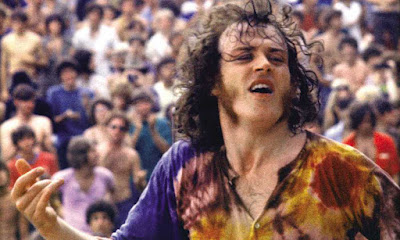

Joe Cocker—in one of the more classic sequences from the film, Cocker belts his hit waltz-time man-possessed soul cover of the Beatles' "With a Little Help From My Friends."

Country Joe and the Fish—the first film sequence featuring the band is their song "Rock and Soul Music."

Arlo Guthrie—Guthrie looked out at the huge crowd, noted the numbers and commented "Lotta freaks!" then launches into "Coming into Los Angeles"

Crosby, Stills, and Nash—new member Neil Young played in their electric portion, but when the harmonizing trio went acoustic he bowed out. The film features a performance of "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" followed by a comment from Stills:

This is the second time we've ever played in front of people, man, we're scared shitless.

Ten Years After—Alvin Lee's blues band plays an intense version of "I'm Going Home" and the film has a three-screen presentation set mostly on Lee's face.

Jefferson Airplane—in the initial cut, the band's relegated to one song "Saturday Afternoon", but the Director's Cut includes two more, "Won't You Try" and "Uncle Sam's Blues."

John Sebastian—the front-man for The Lovin' Spoonful wasn't even scheduled, but was in the audience and coached onto the stage to fill time for the next act to arrive. He sings "Younger Generation."

Country Joe and the Fish return for "The FISH cheer" and the acerbically cheeky "Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-To-Die-Rag"

Santana—Carlos Santa's jazz-rock band performs a furious version of "Soul Sacrifice" and while the film does give Santana his solo shots, the emphasis is on the band's incredible rhythm section.

Sly and the Family Stone—the eclectic generator of hits puts on a great show, encouraging the huge crowd to sing-along to "I Want to Take you Higher" after finishing off a thumping version of "Dance to the Music."

Janis Joplin—"Pearl" does an ecstatic version of "Work Me, Lord" (which was—stunningly—left off the original cut, but re-instated to the Director's Cut). Joplin did her show at 2 in the morning, but she doesn't betray any tiredness in a rangy voice that never wavers from her dancing performance, accompanied by the Kozmic Blues Band.

Jimi Hendrix—the final act, done on the last day, where half of the audience had already left, anticipating the grueling exit from Yasgur's farm through the small town of Bethel. The 1970 version leaves out his performance of "Voodoo Child" and starts with Hendrix's iconic stunning electric version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" and finishes with a stormy haunting performance of "Purple Haze" to bring the curtain down...if there was a curtain.(Jeez, I'm exhausted!)

Quite the presentation. But, still, even the four hour edit leaves out such bands as "The"

Band, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Grateful Dead, Blood, Sweat and

Tears, Ravi Shankar, Tim Hardin, Melanie, Johnny Winter, and The Paul

Butterfield Blues Band. One should be grateful for what one has, and agreements had been made with some of the performers for various reasons (B,S,&T, for example, didn't like how their performance sounded). But, it's a great highlights reel, condensation, and representation, and maybe a palimpsest for another cut somewhere down the long road.

But, Woodstock did its job. The film saved the promoters of the festival from financial ruin after giving up trying to sell tickets to a crowd that just showed up.

In 1996, Woodstock—which won the Best Documentary Oscar in 1971—was inducted into the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." All the films put in the Registry fill that bill, in one way, or another, but, with Woodstock, it feels like an understatement.

Woodstock, the festival and film, are equally and separately, something of a miracle.

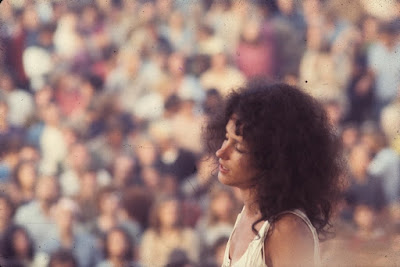

The crowd: too big to fit the frame

Schoonmaker, Murch, Wadleigh and Scorsese

* The Director's Cut, released in 1994, runs 224 minutes and that's the version I watched.

No comments:

Post a Comment