or

"Am I On Fire?"

Not a "car-guy." Never have been. Give me an engine and four wheels and I'm happy. I don't associate myself with horse power, don't give a damn about "cubes," and don't equate my manhood with the make and model of what gets me around.

And I'm enough of a cynic that, although I have a model of James Bond's Aston Martin DB5 sitting on my window sill, I resist the urge to see if it's leaking oil on its base as per its reputation (it's not that accurate!). For me, if it goes, it's good.

So, racing movies leave me cold. Whether The Crowd Roars or Speedway or Grand Prix or Le Mans or Herbie: Fully Loaded, they're empty movies with a lot of hardware beauty shots and cardboard characters who can't really explain the pull of the mystique of racing, when it boils down to making a lot of left turns at high speed.

Ron Howard's Rush came closest to a good racing film because, although it had its own fair share of carburetor-porn, it was about two racers with a love/hate relationship that lasted over years and tracks, and how the two bickered and supported each other owing to their personalities and how it extended over the years because, and in spite of, the competition. They saw each other's value beyond who was first and who was second.

So, at the end, racing movies have had a checkered past.

But, director James Mangold's Ford v Ferrari is the first one I've seen that is entertaining, has its requisite gross weight of Ford/Ferrari fetishism, and even turns the corner on attempting to communicate the need for speed and the intellectual pursuit of putting as much potential energy into a motor engine.

The story, which is based—for the most part—on fact, tells of how the Ford Motor Company, under the leadership of Henry Ford II (in the film, Tracy Letts), and at the urging of Lee Iacocca (played in the film by Jon Bernthal), sought to change the image of Ford, which had suffered set-backs in the family-vehicle field, especially with their Edsel model. Iacocca saw Ford as staid and wanted to make it hip and jazzy to appeal to the Baby-Boomers who were just entering their market share. For Iacocca, it was a matter of style over substance and he wanted to push the planned "Mustang" model as pure "sports-car" material by pushing it into racing. This was to attempt to bite into the Italian car-market, especially Ferrari, whose cars had been dominating the 24 hours of LeMans.

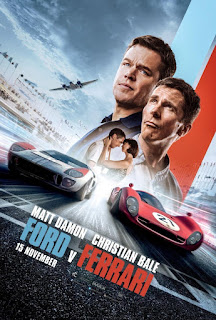

After Iacocca fails to come to terms with Enzo Ferrari over the acquisition of his car company, it turns into a grudge match—Ford II becomes determined to beat Ferrari at LeMans—and Iacocca turns to former LeMans winner Carol Shelby (Matt Damon) to modify a Mustang GT to compete at the French race, and gives him 6 weeks to do it.

It is a daunting task, and to drive, Shelby turns to Ken Miles (Christian Bale) a professional driver and mechanic who is brilliant at what he does, but is self-described as "not a people-person" (which, if I recall, was not a phrase used in the early 1960's). Uncompromising, a perfectionist at engineering and on the race course, Miles thinks making a Ford car race-worthy is an impossible task ("unless you got two, three hundred years"), especially given the corporate group-think entrenched at Ford.*

But, an IRS lien of Miles' garage makes him think twice, and he takes on the job, rubbing—as he does—the Ford execs the wrong way. Those middle-men—especially Leo Beebe (played by Josh Lucas) tolerate Miles' tinkering with the T, which he feels has potential when working with Ford engineers and the Shelby team to shave the design of the model, while also fine-tuning the engine to achieve maximum RPM's. But, when it comes to Miles actually driving the car in the race, that's where they drop the yellow flag. Miles is not a "Ford man," he's not a team player. So when the first race-prepping for LeMans occurs, Shelby is strong-armed to replace him with a more "acceptable" driver...to the Ford execs.

The result is not a "win" putting the entire racing project into question—especially when Ford II's ego is on the line—and Shelby has to use tough-talk and a challenging personal relationship with the CEO to not compromise in his efforts, especially in response to the interference of Ford middle-men.

It's an interesting dynamic. Innovation against corporate interests, all engaged in their own war with different concepts of what constitutes "winning," and pushed to the point where the very goal of winning is in jeopardy as compromise compromises the intended goal. For all the "we're all on the same team here" happy-speak, it is impossible if the goals are different. Sometimes, getting your way gets in the way.

Getting in the way is only a defensive measure on the race-track. And how Ford v. Ferrari characterizes Miles makes him the perfect-combination of driver-engineer, able to perceive not just the performance of his vehicle, but its potential to outlast and out-perform his competition, giving him an advantage in moments of opportunity. The race sequences are thrilling and kinetic, and, combined with its emphasis on character and stakes makes it far more involving than most films of the type coming down the pike.

And Ford v. Ferrari is unique in that it manages to convey that adrenaline kick that fuels drivers and their love of the competition. It does that so well, it should also should have a warning suggesting a designated driver for the ride home.

|

| Damon and Bale, Miles and Shelby |

No comments:

Post a Comment