The Window (Ted Tetzlaff, 1949) Film noir is that darkened crusty under-belly of American cinema made in the jaded post-World War II era of film-making, where the pre-war rose-colored glasses were slapped off people's faces exposing the corruption of power (no matter how menial their power is) and how common folks with a conscience might become prey to the whims of Fate. Those films were suspicious of innocence (somebody's always guilty of something) and sneered at respectability because no fortune was ever made without a little larceny. The ambiguous Raymond Chandler phrase describing them that I always loved was that they took place where "streets were dark with more than Night." Some corruption of the Soul and Nature lurked where the halogen-lights couldn't reach and permeated them beyond the fact that they were B-movies that didn't have the budget for a lot of fancy studio-lighting.

They were usually black and white, but the subjects were always shades of a dusky gray.

The darkest of these that I hold dear to my heart is Kiss Me Deadly, where even the hero is such a low-life degenerate that the Universe conspires to destroy the world in a purifying nuclear fire-ball.

But, the sickest, most twisted one is this new one to me, RKO's The Window, made in the streets of New York's Lower East Side during the winter months of 1947-1948, but not shown in theaters until 1949 (because new studio owner Howard Hughes considered it "unreleasable"). When it was finally allowed to see the light of the projector, it became a huge hit for the cash-strapped studio.Nine year old Tommy Woodry (Bobby Driscoll) is what the spin-doctors would call "a fabulist." And what the internet would call "an entrepreneur." He lies. Well, he makes things up...just like an entrepreneur. His latest whopper is that the family is moving out "way out West" "Texas" "Tombstone" "to a ranch", but when the Landlord suddenly shows up at dinner to show the apartment to prospective renters, Tommy's parents (Barbara Hale and Arthur Kennedy) know the score. Tommy's been lying again, telling his lurid tall tales of cops and robbers and cowboys and indians. The parents severely reprimand him and he's sent to bed. It's Summer, he's out of School, and New York simmers with a heat wave. He sleeps...barely...with the window open and the constant awareness that one boy's ceiling is another man's floor; the movements of the upstairs Kellersons (Paul Stewart and Ruth Roman) are constantly creaked and groaned to him in his room.

It's too hot to sleep in there, so he decides to sleep out on the fire escape, but climbs to the next level to take advantage of a rare breeze and he wakes up when there's some activity in the window of the Kellersons. What he sees is a guy seemingly passed out on the kitchen table and Mrs. Kellerson taking cash out of the guy's wallet. The guy wakes up out of his supposed slumber and attacks her, only to be caught up in a fight with Mr. Kellerson. Soon, the guy falls to the floor, stabbed in the back by a pair of nearby scissors administered by the Mrs.Seems the Kellersons are in a not-so-neat little game of bait-and-switch-blade with the Mrs. luring sailors to their place, knocking them out before they get too demanding, and either rolling them, or—if they're too much trouble—killing them. Tommy has just enough time to tell his Mom what he saw—she tells him to go back to sleep, he had a nightmare—before he goes back to retrieve his pillow below the murderous couple take the body up the fire escape and across the roofs to dump it in the abandoned tenement next door.

Tommy is scared to death. He knows the Kellersons are bad, but when he tells what he saw to his Dad (as Mom was no help!), who has just come home from his night-shift, he gets another lecture and a useless case of the guilts. All the while, in his bedroom alone, he hears the Kellersons' footsteps on his ceiling, and he's left thinking: "I'm the only one who knows. As long as the Kellersons don't know that I know, then I'm safe. But, I need to tell someone." So, the next morning, he climbs out of his bedroom window, goes down the fire escape, and tells the police.

And they don't believe him, either! But, there is one detective (Anthony Ross), who decides to get the story, so he decides to see the Woodrys and see what he can discover. What he finds are frustrated parents, who are embarrassed that their kid has dragged the authorities into his little white lie that is getting bigger and darker by the hour. Something needs to be done about this, and if time-outs won't do it, some advanced shame may be the key to stopping Tommy's lying ways.

And they don't believe him, either! But, there is one detective (Anthony Ross), who decides to get the story, so he decides to see the Woodrys and see what he can discover. What he finds are frustrated parents, who are embarrassed that their kid has dragged the authorities into his little white lie that is getting bigger and darker by the hour. Something needs to be done about this, and if time-outs won't do it, some advanced shame may be the key to stopping Tommy's lying ways.

But, detective Ross isn't done digging yet. He goes a flight up and talks to the Kellersons, posing as a building inspector, which puts both the upstairs neighbors a bit on edge: the husband just casuals his way through it, but she's visibly jittery. Ross concludes it's just a false alarm, even though there's a suspicious stain on the carpet. And the Kellersons are starting to feel that things are starting to close in on them.

But, the damage has been done: what Tommy knows has gotten out of the bag, and he no longer has control of the information. Suddenly, everything he thought he knew about his parents and cops has been proven absolutely false, and as the situation starts to get out of control, Tommy realizes that his life may be in serious jeopardy, and to his terror finds out that it is absolutely true. He must rely on himself to get out of trouble, as the adults (with all the power) are doing nothing to help him, and—in their efforts to work out what they perceive as problems—end up putting him in harm's way.

For Tommy, it's a right of passage (one could say this is also a perverse kind of "Coming of Age" movie) as he has to grow up, and take matters into his own hands. Even so, for all the lessons learned, ultimately the only way he can get out

of his nightmares is—ironically—to take a leap of faith and trust that a group of

adults will do the right thing...for the first while in a long while.

Watching The Window, I was constantly amazed how cynical it was, how relentless and mean-sprited, but also how diabolically smart. It sets up a trap for its young protagonist (Bobby Driscoll is brilliant in this, with a child's eyes, but an adult's questioning eyebrows) and keeps making it worse and worse, until he is forced to take action for himself, and not go running for the aid of his immediate authority figures. It's a shadowed lesson in self-actualization when everything around you is turning against you.

And here's another thing: The Window not only has the adult themes of murder, deceit, and sociopathy, but dares to invade the protected space of kids, and adding to the usual suspects of noir sins on the rap sheet, it includes child neglect and child abuse, leaving one particular bowery boy with nowhere to run to—his parents don't believe him, the police don't believe him, and all his authority figures let him down. The only adults who live up to his view of them are the murderers, who have no qualms about murdering a child to save their own skins.

And here's another thing: The Window not only has the adult themes of murder, deceit, and sociopathy, but dares to invade the protected space of kids, and adding to the usual suspects of noir sins on the rap sheet, it includes child neglect and child abuse, leaving one particular bowery boy with nowhere to run to—his parents don't believe him, the police don't believe him, and all his authority figures let him down. The only adults who live up to his view of them are the murderers, who have no qualms about murdering a child to save their own skins.

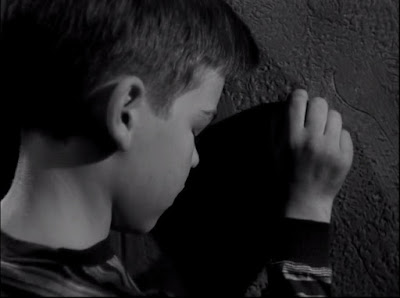

And, as opposed to other film-noirs, it rather boldly includes the purest form of shame—which Tetzlaff shows with the kid's face away from the camera. All noirs have an element of shame to them—all those black silhouettes must have SOME use. The folks in them know they did something wrong, they compromised their ethics, their standards, or their conscience, and are just self-aware enough that they don't need an audience judging them—they mutely judge themselves. But, in young Tommy's case, it's like some hellish retribution for his fibs, putting him through an adult version of Hell, far beyond his years to comprehend.

_6.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment