Robert Earl Wise, Jr. was born on September 10, 1914 in Winchester, Indiana. After his childhood—where Wikipedia states his favorite past-time was going to the movies—he attended Franklin College, intending to pursue a career in journalism on a scholarship. But, in his second year, he moved to Hollywood, where his older brother David had secured a job at RKO Studios, where he did odd jobs (including working in the shipping department) before securing a job editing, first sound (where one of his first jobs was to sync up the morse code sounds on the RKO logo), then picture, working with RKO's editing head William Hamilton, receiving his first co-editing credit on the film The Hunchback of Notre Dame and his first solo editing credit on Bachelor Mother. Wise became known for working creatively under budgetary constraints, his studious preparation, and miserly frugality. In RKO's studio system, making the best for the least paid off and he became well-known and respected, even innovayive, leading to a plumb assignment that would make cinema history. Wise's first Oscar nomination for editing was garnered for his work on Orson Welles' film Citizen Kane and was working on the director's follow-up The Magnificent Ambersons, when, after what was deemed "disastrous" previews, Welles was dismissed from the studio. Per RKO mandates, Wise supervised a hasty re-edit of the film (against Welles' wishes) and supervised the direction of new sequences (including a new ending) to cover the story-gaps. When producer Val Lewton fired the director of an odd sequel to one of the studio's big hits—for falling behind the production schedule—Wise was called in to try to save the production's fortunes.

The Curse of the Cat People (1944) (Gunther von Fritsch/Robert Wise) Wise's first directing job (after years of editing for RKO) began with this odd sequel, one of the few that is better than the original, Curse features the cast from the first but turns it on its tail. Oliver (Kent Smith) and Alice (Jane Randolph) are married and their daughter, Amy (the melancholy little Ann Carter) is troubled—attacking other children viciously and living in a fantasy world with an imaginary friend—who just happens to be Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon), the "cat-girl" from the previous movie! Is "cat-scratch fever" communicable?

Curse actually has little to do with Cat People—all the species are dead and Amy might be haunted by the reminders of her father's first wife (who is never mentioned in the house), so that she imagines Irena. Given the family history, Dad discourages her little flights of fantasy, thinking it could lead to the tragedy of the first film, a tactic that confuses Amy and makes her distrustful of her own family. Then, she is glommed onto by a grasping older actress who lives down the street (Julia Dean). You know those older actresses, they can be pretty dramatic and this one favors Amy over her own daughter (Elizabeth Russell). Not a movie about monsters in the shadows, but the ones in our minds. Although one could make a case for for it being about possession, it's not a horror film, but instead an atmospheric fantasia about the dark side of childhood imagination and alienation, as potent and strange as The Innocents or Night of the Hunter.

Mademoiselle Fifi (1944) Based "on the patriotic stories of Guy de Maupassant," this Val Lewton production plays a bit like a set-bound Stagecoach set during the Franco-Prussian War, circa 1910. A team of stuffy French citizens are held captive at an inn by Prussian lieutenant von Eyrick (Kurt Kreuger), unless the common laundress Elizabeth Rousset (Simone Simon)—who has been barely tolerated by the snooty passengers—dines with with him in the evening. She is a patriotic French-woman and refuses, and although initially supported by the others (who are not so principled), they turn on her when the inconvenience becomes too much for them. To her "fellow travelers," ideals can be dispelled for the slightest of reasons, but the humble laundress still maintains her zeal for France, despite the mocking of her Prussian host...and the disdain of the French upper-crustiness. When the lieutenant insists on accompanying them back to the laundress' village, where he takes his position of "führer," the tensions escalate and become deadly.

The film is very low-budget ($200,000) with the simplest of snowy location shots and much work done in the RKO "European village" (enhanced by cardboard sets at times, even a church belfry is merely a process shot) and it is only once in awhile that Wise shows a particular flair for staging and composition. Despite the low cost, it didn't turn a profit, but is a curious example of a WWII propaganda film hiding under the safety of a period piece. It's also a good example of a film complying with the Hays Code and skirting it, as Elizabeth is a prostitute in the original story and the "dinner" has her as the main course, however, two murders occur and the assailants both survive without punishment as the film ends.

The Body Snatcher (1945) Dr. Wolfe MacFarlane (Henry Daniell) is a teaching professional and surgeon in London, haunted by the limits of his knowledge that would improve his skills and medical knowledge. A student of Dr. Robert Knox, who employed grave-robbers to provide cadavers for his surgical lectures With his third film, a low budget horror film based on the Robert Louis Stevenson story (itself based on the Burke and Hare grave-robbing scandal in London), Wise got to work with an acting legend, Boris Karloff (as well as Bela Lugosi, relegated to a lesser role at the insistence of Karloff after the Hungarian actor received the lion's share of praise in their previous collaboration, Son of Frankenstein), who used his weight to influence his way, as he had just signed a deal with RKO after leaving Universal Studios. In his defense, Karloff was shooting two films simultaneously for producer Val Lewton (who'd had a hand in the script). Wise, ever the diplomat, held his praise for Henry Daniell "as far from a complainer as I've ever known...he'd walk on the set, do his job like the pro he was, do it damn good, and then quietly leave without being a burden to anyone. Period."

A Game of Death (1945) A remake of "The Most Dangerous Game" based on the Richard Connell story (there's even some footage re-used from the pre-Code 1932 version). This was probably made by RKO as they couldn't re-release the original due to the Hays Code and because in that version, the villain is Russian—but as this was WWII-era, the Russians were seen as allies and so the villain is German, the mad hunter Krieger (Edgar Barrier). Krieger, a big game hunter of great renown, became dissatisfied with hunting in the wild and now, on his own private island, he has stocked the island with all sorts of big-game (which we never see), but he has since moved on to a new kind of game, the most dangerous kind...hunting man. He lures ships to crash on his reef and those who survive to the beach, he provides fine accommodations before setting them loose in the jungle for him to track and kill. This is how hunter Don Rainsford (John Loder) and brother and sister Robert and Ellen Trowbridge (Russel Wade and Audrey Long) find themselves together in Kreiger's trap.

There's not a long distance between this John Loder version and the Joel McCrea-Faye Wray version of '32, except the tone—try as he might, Wise can't match the perversity of the first version (we never see the "trophy room", for instance) and concessions are made for the Hays Code—Robert Trowbridge only pretends to be an insufferable drunk—but, it's okay for Krieger to have vicious hounds on the premises and to stalk his helpless prey. And only one of Rainsford's "malayan traps" that he's prepared the previous night is encountered. The violence occurs off-screen, mostly, and not lingered upon. But, it pales to the original in its ability to portray the sheer creepiness of the concept, which became a staple...and then, a trope, for most television adventure series.

Criminal Court (1946) Smarty-pants lawyer Steve Barnes (Tom Conway) is well-known for using "cheap courtroom theatrics" which would make Perry Mason bluster in objection. But, sometimes the tactics you use in court can work against you in real life. He's starting a campaign to run for District Attorney and doing a lot of surveillance work on local racketeers. While doing one of those "exploratory" functions for backers, he leaves the room unnoticed—he's received a call from racketeer Vic Wright (Robert Armstrong),owner of the Circle Club, saying he he wants to show him something damaging to any potential campaign. Barnes shows up, scoffs at the "evidence" and takes out a lighter and burns it. What happens next isn't so clever: after an altercation with Wright, the gangster pulls out a gun. Barnes grabs his arm, knocking the gun out of his hand. The gun hits the edge of a desk and fires, hitting Wright through the pump. He's dead. Barnes doesn't touch anything and leaves. A little complication, though: Steve's girl (Martha O'Driscoll) has just been hired at the Circle as a chanteuse—note: two songs to fast-forward through—and she's the one who next enters Wright's office...and find the body...and TOUCHES the gun. Aaargh! She's arrested, and try as Barnes might to tell them what really happened, nobody believes him because "that's just the sort of story you'd tell to get your dame off the hook." Cried "wolf" a few too many times. it seems.

Wise strips this B movie—his first since leaving Val Lewton's unit at RKO—down to its bare essentials, and keeps the thing moving and moving fast (it only clocks in at 60 minutes!). The only clever touch is to show Wright's attraction to O'Donnell's singer by starting with an over-the-shoulder shot of him staring at her across the Club's dance-floor and then trucking the camera forward so he gets larger and larger in the frame.

Born to Kill (1947) Pot-boiler based on James Gunn's "Deadlier Than the Male." Set in Reno and San Francisco it tells the story of Helen Brent, a "cold iceberg of a woman," who's "rotten inside" and thinks "most men are turnips," becomes attracted to a brick-wall of a psychopath named Sam Wild ("What I want, I take and nobody cuts in") ,who after killing two people in Reno, follows her like a bad stink all the way to 'Frisco, where he starts to horn in on her society pals, and eventually marries her foster-sister. It all sounds nice n' cozy, don't it?

But toughs like Sam (Laurence Tierney) are never satisfied. As one character says, "every mad whim that enters (his) brain, whips (him) around." Once he gets a taste for the good life, he wants more. Pretty soon, Sam is pushing his wife to get him a job running her father's newspaper because "he can do it better" and once he gets real power, "I can spit in anybody's eye! I'll make 'em and break 'em!" Helen would only like Sam to get caught in his bull-headed machinations, but she's conflicted. Something inside her "right down to her roots" makes her want Sam for herself. This can't come to good. No way. No how.

Here, Wise rivals Michael Curtiz in filling his shots with odd details, and then, in moments of high impact, dousing the screen in black simplicity. Wise pulls off the murders, evoking a building horror on the part of the audience, and he's ably abetted by a idiosyncratic cast of character actors who straddle the fence of right and wrong.

But the two stars are Claire Trevor (who made a career and won Oscars for playing "bad" women), and Lawrence Tierney, in what amounted to his first starring role, and his last. Tierney was a rough character, who might have been the nastiest guy in Hollywood when Otto Preminger wasn't in town. On the commentary track, noir student Eddie Muller talked about how, for most actors, stunt-men replaced them in fights to keep them from getting hurt. With Tierney, you replaced him because he didn't know when to stop. Tierney, the actor, had all the mannerisms of a silent-film star, and not for the good, but you couldn't deny when he got angry he could provide an authentic "prison-yard stare." You may remember Tierney for his last major role--the concrete-voiced Joe Cabot in Reservoir Dogs.

Mystery in Mexico (1948) Quickie (slightly over 60 minutes) programmer for RKO to take advantage of their half-interest in Churubusco Studios in Mexico. Horn-dog insurance agent Steve Hastings (William Lundigan) is pretty ambivalent about going south of the border to find a missing fellow-agent who was investigating some missing jewelry, that is, until he sees a picture of the agent's sister Victoria (Jacqueline White), who is also flying there to try and meet her brother. He goes far beyond making a smirking nuisance of himself in trying to get information to the point where you wonder why he isn't constantly sporting cheek bruises and suit-stains from thrown margaritas. Wise makes good use of location shooting in Mexico City and Cuernavaca with a lot of local color in the form of ubiquitous mariachi bands and even a jai-alai contest. And, when he gets away from sun-blasted landscapes, he does some wonderful lighting effects to provide the "Mystery" of the title. Things happen very fast—it is only an hour—and the emotional yin-yanging on the point of the heroine towards the hero is almost schizophrenic. But, the film, despite the sunny locations, is considered a film-noir, probably because the world seems stacked against any moral high ground, and everybody is so underhanded that you can't trust anybody, not business professionals, not the police, not your driver, and not even your own brother. Even in sunny Mexico, the world is corrupted by shadows.

Blood on the Moon (1948) "S'no law that says a man has to stay on the wagon-road, is it?" RKO programmer starring Robert Mitchum as saddle-tramp/gun-man Jim Garry, who stumbles on a range war between independent cattlemen and the guy he's signed on with, Tate Riling (Robert Preston). Riling's working with the government to cheat the long-established John Lufton (Tom Tully) to sell them their beef for cheap by having them forced off grazing land. Riling has also conned some old-timer homesteaders (like Walter Brennan) into going against Lufton when the plan is they're going to get run off too. Thing is, Lufton seems like a good guy and his daughters, Carol (Phyliis Thaxter) and Amy (Barbara Bel Geddes) are loyal and devoted. But, things are much more divided than they appear with double-crosses and triple-crosses in the mix and there ain't no wagon-road to show the way of what's right. It takes Garry some time before he can look at the real bad guy and say "I've seen dogs that wouldn't claim you for a son." Between Wise's moody lighting, the gritty bar-fights with considerable damage done, and conflicts of the conscience and shady government types, one could make a case for a western/film-noir hybrid. Mitchum's scuffed-up cowboy betrays scars but no emotions and isn't always sure to win a fight. But, he's got a sure-fire exit line: "Well, I'll drift..."

The Set-Up (1949) Nearly perfect boxing film done in nearly real-time from the opening frame when a couple of small time managers are talking about the chances of Bill "Stoker" Thompson (Robert Ryan) being able to win his scheduled fight that night. Its pre-arranged that he should "take a fall", but 1) Thompson isn't told about it (so sure is his manager that he's going to lose, anyway) and 2) Stoker is determined to win to show his wife Julie (Audrey Totter) he can still make it in the fight game despite his age. Wise uses his film-noir/horror roots to film in the deepest blacks and whites and was particularly proud to show a "warts-and-all" spectrum of the fight business from the nervous rookies puking before their first fights to the past-their-prime punching bags who can barely remember their name even before they go into the ring. And then, there are the adrenaline-junkies and cheap-thrill addicts, who make up the bulk of the ring-siders—they get their own time in the glare of Wise's spotlight. A simple story, stripped right down to its trunks, but it's a B-movie with A-movie aspirations, calculating the odds in the zero-sum game in one movie's running time.

Two Flags West (1950) An odd foot-note in American history is the basis for this Western—during the Civil War, President Lincoln issued pardons to all Confederate POW's if they would volunteer for the Cavalry in the Indian Wars. When Col. Clay Tucker (Joseph Cotten) accepts this duty on behalf of his men, he is assigned to Camp Thorn, whose hobbled commander Maj. Henry Kenniston (Jeff Chandler) has had some common experience, having escaped from a Confederate Camp. On the surface, he welcomes the help from the Reb's, but deep down he resents them, especially Tucker's role in campaigns that have killed his brother, leaving a widow (Linda Darnell) that he dotes on and probably covets. The animosity Kenniston holds for Tucker is only the most simmering example of what is brewing between the blue and the grey troops stationed at Fort Thorn, New Mexico, a mere stop-over on the way to California. Such a remote position in the middle of nowhere is probably a safe bet for such troops as the reb's and the best-out-of-the-way Kenniston. They can be quietly ignored while the Army concentrates on the Civil War, out of sight, out of mind. But with Southern sympathizers who see it as an opportunity to bring California to the aid of the South, and a bitter vet in charge, who just barely keeps his anger under control, it should probably bear a bit more scrutiny. Wise does some channeling of John Ford in his elegiac compositions and asides, the cast boasts a fine collection of characters actors, but Cotten roots the movie with his Virginian background and his courtly manner.

Three Secrets (1950) The first words of the movie lay out the basic problem to be solved in the movie:"Mommy, when we gettin' home?" A plane crash in a high remote area near San Pedro looks like there are no survivors, but photo analysis shows that one 5 year old child has survived. As search parties start getting ready, it's revealed that little Johnny is adopted...so...who's the real parents? Well, considering the plane crashed on the way back to celebrating Johnny's birthday...

Well, it'll take the whole movie and lots of flash-back footage to find out. The three women who hear about it and are most concerned—tough newspaperwoman Phyllis "Phil'" Horn (Patricia Neal) gave up her child after a divorce, Susan Chase (Eleanor Parker) gave up her child after an indiscretion with a Marine and is now comfortably married to a lawyer, and showgirl Ann Lawrence (Ruth Roman) gave up her child because she was serving a prison stretch, for killing the rich bastard who threw her over. But, that's flashbacks, who's going to get the kid if and when they can get him off the mountain? If the formula sounds a lot like the previous year's Letter to Three Wives, that's because it's the same template and the same brand of soap. Even if you do figure out who the mother is, there's still the decision of who's going to take the kid. I smell noble gestures happening—that is, if the film follows formula. It does.

The House on Telegraph Hill (1951) Victoria Kowelska (Valentina Cortese) survives Bergen-Belsen with her friend Karin Dernakova who tells her of her son whom she sent away to San Francisco in the U.S. with her Aunt Sophia. Karin dies and when the camp is liberated, Victoria assumes her identity to get passage to the States. When she gets to New York, she finds out Aunt Sophia has died and the boy has gone to the legal guardian Alan Spender (Richard Basehart). Spender's legal team is suspicious of "Karin" as her son has inherited her Aunt's fortune. But, Spender is attracted to "Karin" and marries her within three days of meeting her and takes her back to Mandalay...er, the House on Telegraph Hill, where she must contend with the way Aunt Sophie's portrait stares at her...as well as Margaret (Fay Baker), who is son Christopher's care-taker, and takes to "Karin" the way Mrs. Danvers takes to Rebecca. On top of that, one of Spender's best friends is the very same Major, Marc Bennett (William Lundigan), who handled Victoria's papers when she was first liberated from Belsen. Fancy that!

Pretty soon, "Karin" is jumping at every shadow, every creaking floorboard, miffed at every slight, and starts to become very nosy about the place—like the playhouse that has a hole blown out of it..."by accident." And the time, she decided to take the car out...and the brakes failed...in San Francisco?

It's a stateside Rebecca, with the switched papers providing a good angle of how to introduce the woman-in-peril into the situation. And if you ever want to know where Meryl Streep got her "slovak" accent in Sophie's Choice, check out Valentina Cortesa in this film.

After a 22 year stint at RKO, Wise, now directing A-list pictures, took a 3-year contract with 20th Century Fox, starting his career with them with a humble, B-list science fiction film, which, nevertheless, capture audiences' imagination and became a classic of the form...

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) Iconic sci-fi pic that managed to be just strange enough to be spiritual without having to explain itself. Edmund H. North's script (adapted from the 1940 Harry Bates story "Farewell to the Master") just assumed that any advanced civilization's technology would seem like magic to us (ala Clarke's Third Law). It's anti-nuke theme was somewhat off-set by it's Christ allegory under-pinnings: a human-appearing being from above comes to Earth with a "message," is killed and resurrected to give mankind a lesson in humility. That the alien--Klaatu (Michael Rennie)--walks among us under the guise of a "Mr. Carpenter" just nails the significance home.

Right from the get-go, The Day The Earth Stood Still announces its intention with a "spooky" theremin-laced score (by the brilliant Bernard Herrmann), quite at odds with its message of peace. Wise shows a global humanity surrounded by its current technology (radio, television, radar) spreading the news of an invader from space, which lands in the Mall area of a tourist-clogged Washington D.C. in Spring. Phalanxed by a wall of tanks and military might (with a larger crowd of tourists behind it) the alien presence reveals itself and is shot by a panicky soldier for its trouble. Before you can say "Kent State," the alien is taken to Walter Reed to be treated, observed and questioned, and the formal Klaatu--patient, curious, but with a hint of passive condescension--does his own analysis, escaping from the hospital and blending with the populace as "Mr. Carpenter"--taking a room at a boarding house, becoming involved with a widowed secretary (Patricia Neal)--it IS the '50's, after all--and her son, seeing humanity first-hand.

Meanwhile, his Enforcer, Gort, a lumbering, laser-cyclopsed, soft-metal robot stands guard over the saucer, turning his evil eye on any hint of aggression, without any regard to how much of the GNP was flushed to make those tanks. If Gort could laugh when he turned on his eye-light, he'd probably do it with glee.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is a classic film—a time-capsule, of a kind—from a different time and place and space that reminds, yes, with great power comes great responsibility--but there's always someone more powerful, who might take yours away, and make you stop and smell the fall-out.

The Captive City (1952) The first movie made by Aspen productions (formed by Wise and fellow RKO editor-director Mark Robson), The Captive City is a very cheap film noir based on true incidences but heavily fictionalized and photographed (again) on location in Reno, Nevada, not quite in a cinema verite style but darned close. Local paper editor Jim Austin (John Forsythe in his first starring role in a film—he might have been familiar to television audiences) has a nice little community paper going, but he gets a scoop from a informer he thinks is a crank; a local PI has had his license revoked by the police. It seems he's been working for the ex-wife of one Murray Sirak (Victor Sutherland) in a divorce case. Sirak is an insurance salesman, but he's more into making sure that the insurance is needed as he runs a series of book-making businesses as well. And business is good. Austin makes some inquiries with the police and city officials and is reassured that the guy's had a bad history and Austin ignores his repeated phone calls. Until they stop coming. Turns out the guy's a victim of a suspicious hit-and-run. And the more Austin digs into it, the more resistance he gets, his advertisers start to pull out of the paper, and his business partner decides maybe a little lucrative graft can be lived with. Finally, he begins to feel pressure from the police, who, even though they cooperate with Austin to a certain extent to show him the hopelessness of his crusade, start to follow him, forcing him to make a run for it to the State Capitol to plead his case to the Kefauver Committee. Kefauver was a U.S. Senator investigating various vices in the U.S. and had high hopes to use the film to further his political interests—which, I suppose, one could see as influence.

Wise, in his first film for his Aspen Productions, was able to achieve an A-film look to his cheap B-film, thanks to "the Hoge lens" which gave his film a seemingly infinite depth of field, not unlike Citizen Kane.

Something for the Birds (1952) Anne Richards (Patricia Neal) is an environmentalist with the SPCC (The Society for the Preservation of the California Condor) wading her way through the halls and ballrooms of Washington D.C. to protect a habitat marked for natural gas drilling. She may be a fan of condors but the vultures of Capitol Hill are quite another matter. Luckily for her she meets one of the flock of D.C. wannabe's "Admiral" Johnnie Adams (Edmund Gwenn), a regular fixture at Washington functions—he's an engraver by trade, and never been in the Navy but someone thought he was an admiral at some point and he's never corrected the mistake for, in Washington, the impression of power is everything. Through Johnnie, she meets snaky lobbyist Steve ("Excuse me, while I peddle my influence...") Bennett (Victor Mature), who would like to help, but he's more interested in her "quid Pro quo." Oh, and one of his clients is gas company who wants the habitat's mineral rights. The movie is a nest of duplicity and glad-handering, but, as it's a comedy, it's all in good fun and good governance, one of those movies that doesn't shy away from the awful truth of institutionalized influence, but manages to make a statement for democracy in numbers. Why, it's almost fun to watch sausage being made. Neal is a joy to watch in a comedy role, and although Mature smiles a lot, he seems rather uncomfortable.

Destination Gobi (1953) One of those "untold stories" of World War II with an odd twist—this was about a consignment of "Saddles for the Navy." It's a long story. Chief Boatswain's Mate Sam McHale (Richard Widmark) is tasked by the Navy to lead a troop of meteorologists to the edge of Outer Mongolia to study weather patterns to help plan naval operations. McHale reluctantly accepts the assignment, trading in the sea and ships for desert and weather balloons and is aggrieved to spend months in the desert with a typical cadre of civillian wags (including Martin Milner, Darryl Hickman, Max Showalter, and Ross Bagdasarian and Earl Holliman, who isn't credited) who like to kid McHale about his dependence on chain-of-command and protocol. There is a side-benefit, however—a semi-friendly relationship with a tribe of Mongul nomads who pass through and take a grudging regard for the strangers in their midst—who have no interest in the grass of the oasis which is their staple. Both keep a wary eye for the Japanese zeros who are strafing their encampments, and after one such dust-up, the Navy Yanks find themselves in the same boat as the Monguls—crossing the brutal desert to try to get back to the ocean. The film plays like a Western merged with a war film, only with the Americans taking a much less xenophobic tact with their actions towards the indigenous people (although they still talk tough throughout and are ready with racial slurs for the Japanese enemy). It tries to play the movie for more laughs than it's worth, but it's ultimately a rather light study in culture clashes and cooperation.

The Desert Rats (1953) Two years after James Mason had starred as Field Marshall Erwin Rommel in The Desert Fox, he reprised the role for producer Darryl Zanuck in this low-budget telling of the 241 siege of Tobruk, where Australian and Italian troops held off Rommel from moving to Cairo and the Suez. Mason was the top-draw and the most notable name in the cast, despite playing a cameo role. Starring was Richard Burton, just before his break-out role in Fox's The Robe, with support by Robert Newton (three years after starring in Disney's Treasure Island). Burton plays a British "advisor", Captain "Tammy" MacRoberts, charged with making the Aussies crack-troops to repel Rommel's North Afrika Corps. He's a bit of a martinet, not well-liked by the men, but manages to get results and turns the troops into more than just a competent defense, but a fierce commando unit specializing in night-raids on Rommel's positions. Newton plays his former Headmaster, who, though considered "the best of the lot" by MacRoberts and the students, has a hard time keeping away from the drink and his self-estimation as a coward. Burton and Mason have only one scene together—a convenience that feels a bit too planned and too prominent. And it's interesting to see how Mason changes his performance for this film—he's not the reluctant hero here but a cunning adversary—and the performance, mostly in German, seems a bit more like Erich von Stroheim's work as Rommel in Billy Wilder's Five Graves to Cairo. Wise makes the most of the meager budget making a war film that feels mostly set-bound, with few desert scenes that are plumped up by war footage from the fight and Ray Kellogg's visual effects work.

So Big (1953) After two war films, Wise changes pace with an adaptation of Edna Ferber's already-twice-filmed Pulitzer Prize winning novel. Maybe the rigors of location shooting influenced him to make a domestic drama.

We meet Selina Peake (Jane Wyman) at a boarding school where she offers up to her house-mates her well-to-do father's saying: there are two kinds of people in the world—wheat and emerald; wheat people provide sustenance and emerald people are creative, providing the world beauty.

Dad dies, leaving her penniless. But, the family of a school-friend finds her a teaching position for a Dutch farming community. So, she moves from Chicago to the outskirts, where her buoyant ability to find the best in everything—"the cabbages are beautiful!" is one of her sentiments that makes the rounds—endears her to the community, and makes her a bit of a curiosity. She finds a room with the Poole family where she takes an interest in young Rolfe (Richard Beymer, who would work again with Wise, later, as a young adult)—who no longer attends school, tending, instead, the family farm—giving him books and encouraging him to pursue his interest in the piano and composing.

She meets and marries Pervus DeJong (Sterling Hayden), a truck farmer with a lot of land, but no luck raising crops and little education; she helps in the fields and with his "figurin'" at market. Soon, they have a child, Dirk, who, from birth, stretches out his arms, earning him the nickname "So Big." Life takes a turn for the worse when Pervus dies and Selina determines that she'll continue the farm, bucking tradition and raising eyebrows by taking her crops to market herself. Pervus' diligent farming and Selina's improvements eventually pays off and she's able to send Dirk to college to study architecture..

But, Dirk decides, after years of being a draftsman at a prestigious Chicago firm, to take a fast track to a higher income in sales and promotion, which makes him wealthy, but disappoints Selina, a wheat, who had hoped Dirk would become emerald, instead of (as she describes it) "a rubber stamp."

It's a story that runs parallel with Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons (which Wise edited...and helped butcher when Welles was out of the country) where worth and splendor of spirit have more to do with accomplishment than the accumulation of wealth. It's a cautionary tale that may seem out-of-fashion in these days...or even in the days of 1953...or 1923 when it was written. But, it's a nice little endorsement for hard work and gumption than the spoils of avarice.

Executive Suite (1954) John Houseman produces, Ernest Lehman writes and Wise starts out with a bang as executive Avery Bullard (in POV) walks out of a meeting with executives, rides the elevator to the lobby, writes out a cable that he's calling an emergency meeting at 6pm and dies of a stroke hailing a cab. Bullard is the "one man" of a one man corporation, Tredway Industries, and as business abhors a vacuum, the Vice Presidents immediately begin to position themselves for taking over the CEO job. Strategies are concocted, loyalties are tested, and backs are summarily stabbed in the power-grab between factions of a furniture-making company.

It all happens within a 24 hour period and the movie plays like a Grand Hotel of the board-meeting set. With an all-star cast of William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Frederic March (who acts like he's auditioning to play Richard Nixon), Walter Pidgeon, Paul Douglas, Louis Calhern, and Dean Jagger (with June Allyson and Shelley Winters in supporting roles), it is Nina Foch who walked away with an Oscar nomination for her work as Bullard's executive assistant. Wise keeps things moving along with just enough interference from unruly extras that you get the sense that it all isn't being played in a bubble. It is also one of the few movies that gets away without a music score of any kind—nor do you miss it.

Helen of Troy (1956) Wise moves from M-G-M to Warners for this Cinemascope "historical" epic based on Homer's "Iliad." Prince Paris of Troy (Jacques nee "Jack" Sernas) travels to Greece to negotiate a peace with the acquisitive nation, but is ship-wrecked in a storm, where he is rescued by Queen Helen of Troy (Rossana Podesta) and her maid-servant Andraste (Brigitte Bardot—yes, Bridgitte Bardot, just before she was to hit big with And God Created Woman) that would end up creating the war he was trying to avoid. Convinced by Helen that she's a slave to the Queen, Paris falls for her, thinking her the living embodiment of Aphrodite, but once all is revealed, the two are thrown together, and to keep Paris from being killed (after a fight with champion Ajax), they sail to Troy, where the citizenry aren't exactly thrilled once they find out who "the girl" is—the stolen wife of King Menelaus (Niall McGinniss).

Then, of course, the Greeks launch their "thousand ships," Hector (Harry Andrews) and Achilles (Stanley Baker) get into the act, and the Greeks leaving their little "gift" of a horse. What's different about this version is that it takes "the side" of Paris and Helen, even though their actions spell disaster for the glory that is Troy. It is a tough argument to make and no matter how ardent the two lovers may be (and Sernas and Podesta don't make the case very convincingly), one still sees them as selfish and irresponsible—the screenplay doesn't even try to blame it on the Gods, despite Paris' constant harkening to Aphrodite.

Wise (who also produced) shot at Cinecitta Studios in Rome and the film boasts an interesting international cast (save for the two leads) and Wise's compositions make full use of the Cinemascope frame, especially in the big crowd and battle scenes. The overall effect is a bit stilted and lifeless, a bit like the Trojan Horse itself, but doesn't hold as many surprises.

Tribute to a Bad Man (1956) James Cagney (taking over a role Spencer Tracy balked at because of the high frontier location) as rancher Jeremy Rodock ("a hard man to figger") raising horses on the big chunk of Wyoming that he owns. Young Pennsylvanian Steve Miller (Don Dubbins) rides into Rodock Valley, helps old man Rodock out of a jam with horse-thieves and then signs up for a spring on the ranch. There, he mingles with hands, particularly McNulty (Stephen McNally) who has his eyes on "the gal" on the place, Jocasta (Irene Pappas' first U.S. film). Well, with so much space and so little constabulary around, Rodock is only too quick to mete out his own form of justice: take an interest in Jocasta, you're fired; steal any of his horses, he hangs you right then and there. The "hands" are full of tales of Rodock's "hangin' fever" and though he may be sentimental about the horses, he won't back down from his rule of law, despite the Eastern ways of the new kid and the protests of the woman he falls just short of saying that he loves.

Only two reasons to watch this and that's Wise's Cinemascope landscapes and the only guy who could rival them for attention—Cagney. He's never been too comfortable on Westerns, but portraying a man of conflicting emotions (all of them at 100%) then Cagney's your man—Tracy wouldn't have made Rodock nearly as interesting—his posture like a braying rooster when he's full of himself or angry, and with his arms always cocked like he's about to start a fight or he should have reins in his hand. The story's hog-wash, but Cagney's the real deal.

Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956) Paul Newman's second starring role (and also the second with Pier Angeli playing his wife), this adaptation (by Ernest Lehman) of boxer Rocky Graziano's autobiography traces Graziano's youth as a rebellious street-punk (where one of his rival gang-members is Steve McQueen—you'll be amazed how many future character actors are in this movie!) through his tumultuous Army service, his desertion and arrest for that offense culminating in prison time, all the while fighting his own demons (personified by a father played by Harold J. Stone) and anyone daring to get in the ring with him. The film benefits greatly from Newman's performance going from a young pain-in-the-neck to a family man trying to save his reputation from mobsters putting pressure on him to throw fights or face exposing his past as a con. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Graziano has to decide whether he's going to continue to submit and cave in or take a chance and risky his career to be ruined. For any actor it would be a tough transition to pull off, but Newman makes Graziano a believable combination of tough guy, bone-head, and love-struck family man.

This Could Be the Night (1957) Schoolteacher Anne Leeds (Jean Simmons) takes a part-time job in the evenings at "The Tonic", a Broadway nightclub run by former bootlegger Rocco (Paul Douglas) and Tony Amotti (Anthony Franciosa), his younger, hot-headed partner. Written by Isobel Lennart (based on short stories by Cornelia Baird Gross), This Could Be the Night plays like a Cinemascope black and white modern-dress version of Damon Runyon (Simmons had starred in Guys and Dolls two years earlier for Columbia) with the innocent pigeon finding her way amongst the nighthawks, while they're crackin' wise. The three leads have most of the screen-time, but the film is filled with nicely drawn out parts for the nightclub staff, who, one by one, start to affectionately call her "Baby"—although no one comes out and says it, it's because she's a virgin (a "greenhorn," "no runs, no hits, no errors" are some of the colorful verbal dancing they do around it) and in their world, that peculiarity is particularly rare...and to be protected. The character actors collected do some memorable work, particularly Joan Blondell as a stage mother, Neile Adams as her daughter, an aspiring cook and/or showgirl, J. Carrol Naish as the cook, Leon, Rafael Campos as busboy Hussein Mohammad, and particularly Julie Wilson as the house chanteuse/wise-gal, Ivy. Wise makes great use of the Cinemascope frame (Russell Harlan is the cinematographer) in a set-bound movie, and you can see him edging into musical territory—this is for M-G-M—with some nicely integrated musical numbers by Wilson and Adams. Surprisingly entertaining, with some rich dialog and clever blocking.

Until They Sail (1957) Based on a James A. Michener story and a Robert Anderson screenplay—both men served in the Pacific in WWII—Until They Sail is another "service love story" in Michener's vein. The four Leslie sisters—Anne "the iceberg" (Joan Fontaine), practical Barbara (Jean Simmons), Deliah (Piper Laurie) and debutante Evelyn (Sandra Dee)—of Christchurch, New Zealand are keeping the home-fires burning. Dad and Mum are dead, father being killed in the service, and Barbara's husband is serving in North Africa. They keep a map of the locations of the servicemen they've met and the battle-centers they read about in the papers. Deliah, with her beau out there somewhere gets into a hasty marriage with Phil or "Shiner" (Wally Cassell), but when he's shipped off, she ships out to the big city of Wellington, where she engages in a series of loose affairs. There's plenty of opportunity because it's just after Pearl Harbor and the Yanks are in town.

All the sisters find their own lives invaded by the war, as it affects the men in their lives, while they must cope with the after-effects whether "all's fair" or not. Love is found, love is lost and love is wasted in this soapish story of the collateral damage of war, where the lives of women are dictated and determined by men. Paul Newman makes a late entry as a love interest, but he doesn't appear all that happy to be there.

Run Silent Run Deep (1957) One of those general entertainment movies that manages to do so many things exceptionally well that one comes away grateful for the experience. Directed by Wise with a true sense of claustrophobia, the script by John Gay maintains a strict military accuracy while displaying a keen sense of drama, psychology and brevity. A psychological drama, a war film, a story of mystery as well as redemption, the film manages to pull everything off with a propulsive rhythm and fine performances throughout.

Produced by Hecht-Hill-Lancaster, Burt Lancaster the producer takes a back-seat to his star, Clark Gable, the older actor in one of his understated roles that takes into account his age. Gable's the flawed figurehead with shades of Ahab who finagles his way into the command of the S.S. Nerka patrolling the Pacific during World War II, having already lost one sub and and a frustrating convalescence at a desk-job.

Lancaster's exec Jim Bledsoe is torqued because Gable's Cmdr. "Rich" Richardson has pulled rank to get command—his command—and is now drilling the men to dive and shoot a torpedo within a record 35 seconds. The already suspicious crew starts to snarl about all this practice with nothing to show for it. Then a lucky strike convinces some of them the new Captain is golden, while the other half think he's out to torpedo their mission. Lancaster turns into a reluctant arbiter.

Run Silent, Run Deep is an intelligent tribute to the fighting services without resorting to jingoism, racism or choired flag-waving. The film-makers' respect for the professionalism under duress of sub-crews runs silent and deep.

Star! (aka "Those Were the Happy Times")(1968) During production of The Sound of Music, Wise, producer Saul Chaplin and Julie Andrews began discussing ideas for a project they could continue with in order to honor Andrews' two picture deal with 20th Century Fox. Chaplin and Wise thought a biography of Gertrude Lawrence had promise, but Andrews had some trepidation of trying to live up to Lawrence's reputation. The script, and Wise's handling of it, has a two-point structure that initially resembles Citizen Kane—the film begins with a film-within-a-film (with a vintage Fox logo and its own false credits) chronicling the life of Lawrence, while an impatient and less-rigid Lawrence (now played by Andrews) watches in wide-screen and fills in the blanks.

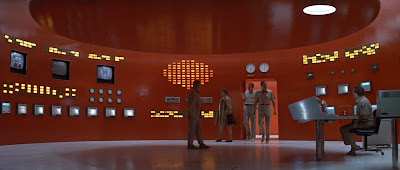

The Andromeda Strain (1971) Robert Wise's return to science-fiction after years in the musical field proved that he was still as effective as a gritty story teller as he was a choreographer. He was intrigued by Michael Crichton's tale of a population-decimating contagion from space, but more that the author made it seem more real by citing scholarly works (all of them fabricated by Crichton). For the movie version of The Andromeda Strain, Wise pulled off a similar cinematic trick to keep it real—he didn't cast stars, just good character actors (and a couple of formidable stage actors) for the leads, filmed what was essentially a "bottle show" (mostly taken place in a contained space with few exteriors in an unfussy, clean style in wide panavision and split-screen, and maybe the first instance of on-screen date/time/location computer updates graphicked across the screen to orient ourselves. It's played out in as un-melodramatic a way as possible with minimum effects. Wise and screenwriter Nelson Gidding do a thorough job of negotiating Crichton's juggled narrative and technical jargon, not withholding anything essential to the investigation no matter how arcane, and then boil it down like a detective story to the central puzzle: why two disparate survivors escaped having their blood crystallized, specifically, how a perfectly healthy squawling baby is similar to a decrepit vagabond with a bleeding ulcer and a taste for drinking sterno. Obvious answers are discarded one by one and it's a neat exercise in re-thinking a problem.

It's smart. And it assumes the viewer is smart enough to follow along, and that's refreshing (especially compared to its mouth-breathing, knuckle-dragging 2008 remake by the Scott Brothers production company), and it's core cast (the irreplaceable Arthur Hill and Kate Reid, David Wayne and James Olsen) does a terrific job of underplaying the drama (the smaller, more bureaucratic roles have a tendency to drift towards hyperbole and easy caricature), and it has a smashing pay-off with one of the best cliff-hangers in sci-fi history (as did the book).

Two People (1973) After the technical work-out of The Andromeda Strain, it must have been a seemed a creative palate-cleanser to make a simple low budget love story shot-on-location (away from a studio) and in sequence. Plus, the successes of Love Story and Easy Rider (and bagging one of its stars!) might have seemed like a good bet for its by-now nearing 60 director. But, again, timing was an issue. After a year dominated by larger budgeted splashy fare like The Godfather and Cabaret, Two People seemed a little too little, too late. Peter Fonda plays a Vietnam War deserter in exile in Marrakesh, who has been persuaded to come back to the States to face punishment. Of all the people to run into, he encounters a conflicted Vogue fashion model (Lindsay Wagner—her first movie) grappling with responsibility issues. The two begin a testy, talky romance as they both make their way from Morrocco to Paris to New York, both mopey over their life-choices. The most interesting thing is the reversal of the Love Story set-up—she's the rich socialite, he's the deep one. But, if you're going to have an existential crisis, it might as well be with a super-model (I wouldn't know!). Wagner is great and game in this, but Fonda vacillates between practiced sincerity and odd acting choices. An odd combination of Vogue and vague.

The Hindenburg (1975) This film came right in the midst of the "disaster" film cycle, so it's marketed like one of those ("Who will die?"), but it's actually an odd little thriller-conspiracy film about a Luftwaffe colonel (George C. Scott) who's been assigned to run security on the initial Transatlantic flight of the Hindenburg from Germany to New York...or, specifically, Lakehurst, New Jersey. Now, we all know how it ends (37 died; 62 survived), so the film is actually more of a mystery-suspense film built around a well-documented tragedy—a speculation behind truth, like any good/bad conspiracy, something of a Hollywood specialty.

The Hindenburg (1975) This film came right in the midst of the "disaster" film cycle, so it's marketed like one of those ("Who will die?"), but it's actually an odd little thriller-conspiracy film about a Luftwaffe colonel (George C. Scott) who's been assigned to run security on the initial Transatlantic flight of the Hindenburg from Germany to New York...or, specifically, Lakehurst, New Jersey. Now, we all know how it ends (37 died; 62 survived), so the film is actually more of a mystery-suspense film built around a well-documented tragedy—a speculation behind truth, like any good/bad conspiracy, something of a Hollywood specialty.

Because the cause of the Hindenburg's sudden immolation is still shrouded in mystery (personally, I think Amelia Earhart's responsible), there is a little conspiracy theory that a saboteur (William Atherton) had rigged a bomb to put a damper on Nazi hubris over their airship, but there's also Scott's security colonel, AND an SS agent (Roy Thinnes), who's malignantly watching both of them and is such a vicious monster that he ends up being a contributor to the disaster, anyway. Oh, the humanity. If the film is somewhat inert—Scott tries bravely to breathe some life into it—the special effects by Albert Whitlock are amazing, combining modern special effects with the seared-in-the-memory newsreel footage...if somewhat lingered over a bit too much.

Audrey Rose (1977) Ivy Templeton (Susan Swift) is coming up on her 11th birthday and she is having terrible, inexplicable nightmares. Could be oncoming puberty, could be the gargoyles festooning the New York apartment building her parents (Marsha Mason, John Beck) inhabit...or it might be the "weird, spaced-out looking guy" (Anthony Hopkins) named Elliott Hoover who seems to think Ivy is possessed of the reincarnated soul of his daughter Audrey Rose, killed in a car-crash only two minutes before Ivy was born. This leads to a restraining order and a court-case that stretches credulity and bests even veteran actors like Robert Walden and John Hillerman.

The movie's full of Serling's clever touches, but one sums it up: "You know, you give the world enough sodas and fishing pools, you'd have so much brotherhood, God would smile!"

Robert Wise spent most of his later career working in the background of the film industry and student film organizations. He won four Oscars, two for Best Director, was President of their organization from 1985 to 1988. He served on the boards of The American Film Institute and The National Student Film Institute. And, with the advent of DVD's, he spent his last years supervising their transfers and providing commentary tracks. His last work was re-visiting Star Trek: The Motion Picture and re-editing a "Director's Cut" and revising some special effects sequences.

Born to Kill (1947) Pot-boiler based on James Gunn's "Deadlier Than the Male." Set in Reno and San Francisco it tells the story of Helen Brent, a "cold iceberg of a woman," who's "rotten inside" and thinks "most men are turnips," becomes attracted to a brick-wall of a psychopath named Sam Wild ("What I want, I take and nobody cuts in") ,who after killing two people in Reno, follows her like a bad stink all the way to 'Frisco, where he starts to horn in on her society pals, and eventually marries her foster-sister. It all sounds nice n' cozy, don't it?

But toughs like Sam (Laurence Tierney) are never satisfied. As one character says, "every mad whim that enters (his) brain, whips (him) around." Once he gets a taste for the good life, he wants more. Pretty soon, Sam is pushing his wife to get him a job running her father's newspaper because "he can do it better" and once he gets real power, "I can spit in anybody's eye! I'll make 'em and break 'em!" Helen would only like Sam to get caught in his bull-headed machinations, but she's conflicted. Something inside her "right down to her roots" makes her want Sam for herself. This can't come to good. No way. No how.

Here, Wise rivals Michael Curtiz in filling his shots with odd details, and then, in moments of high impact, dousing the screen in black simplicity. Wise pulls off the murders, evoking a building horror on the part of the audience, and he's ably abetted by a idiosyncratic cast of character actors who straddle the fence of right and wrong.

But the two stars are Claire Trevor (who made a career and won Oscars for playing "bad" women), and Lawrence Tierney, in what amounted to his first starring role, and his last. Tierney was a rough character, who might have been the nastiest guy in Hollywood when Otto Preminger wasn't in town. On the commentary track, noir student Eddie Muller talked about how, for most actors, stunt-men replaced them in fights to keep them from getting hurt. With Tierney, you replaced him because he didn't know when to stop. Tierney, the actor, had all the mannerisms of a silent-film star, and not for the good, but you couldn't deny when he got angry he could provide an authentic "prison-yard stare." You may remember Tierney for his last major role--the concrete-voiced Joe Cabot in Reservoir Dogs.

Mystery in Mexico (1948) Quickie (slightly over 60 minutes) programmer for RKO to take advantage of their half-interest in Churubusco Studios in Mexico. Horn-dog insurance agent Steve Hastings (William Lundigan) is pretty ambivalent about going south of the border to find a missing fellow-agent who was investigating some missing jewelry, that is, until he sees a picture of the agent's sister Victoria (Jacqueline White), who is also flying there to try and meet her brother. He goes far beyond making a smirking nuisance of himself in trying to get information to the point where you wonder why he isn't constantly sporting cheek bruises and suit-stains from thrown margaritas. Wise makes good use of location shooting in Mexico City and Cuernavaca with a lot of local color in the form of ubiquitous mariachi bands and even a jai-alai contest. And, when he gets away from sun-blasted landscapes, he does some wonderful lighting effects to provide the "Mystery" of the title. Things happen very fast—it is only an hour—and the emotional yin-yanging on the point of the heroine towards the hero is almost schizophrenic. But, the film, despite the sunny locations, is considered a film-noir, probably because the world seems stacked against any moral high ground, and everybody is so underhanded that you can't trust anybody, not business professionals, not the police, not your driver, and not even your own brother. Even in sunny Mexico, the world is corrupted by shadows.

Blood on the Moon (1948) "S'no law that says a man has to stay on the wagon-road, is it?" RKO programmer starring Robert Mitchum as saddle-tramp/gun-man Jim Garry, who stumbles on a range war between independent cattlemen and the guy he's signed on with, Tate Riling (Robert Preston). Riling's working with the government to cheat the long-established John Lufton (Tom Tully) to sell them their beef for cheap by having them forced off grazing land. Riling has also conned some old-timer homesteaders (like Walter Brennan) into going against Lufton when the plan is they're going to get run off too. Thing is, Lufton seems like a good guy and his daughters, Carol (Phyliis Thaxter) and Amy (Barbara Bel Geddes) are loyal and devoted. But, things are much more divided than they appear with double-crosses and triple-crosses in the mix and there ain't no wagon-road to show the way of what's right. It takes Garry some time before he can look at the real bad guy and say "I've seen dogs that wouldn't claim you for a son." Between Wise's moody lighting, the gritty bar-fights with considerable damage done, and conflicts of the conscience and shady government types, one could make a case for a western/film-noir hybrid. Mitchum's scuffed-up cowboy betrays scars but no emotions and isn't always sure to win a fight. But, he's got a sure-fire exit line: "Well, I'll drift..."

The Set-Up (1949) Nearly perfect boxing film done in nearly real-time from the opening frame when a couple of small time managers are talking about the chances of Bill "Stoker" Thompson (Robert Ryan) being able to win his scheduled fight that night. Its pre-arranged that he should "take a fall", but 1) Thompson isn't told about it (so sure is his manager that he's going to lose, anyway) and 2) Stoker is determined to win to show his wife Julie (Audrey Totter) he can still make it in the fight game despite his age. Wise uses his film-noir/horror roots to film in the deepest blacks and whites and was particularly proud to show a "warts-and-all" spectrum of the fight business from the nervous rookies puking before their first fights to the past-their-prime punching bags who can barely remember their name even before they go into the ring. And then, there are the adrenaline-junkies and cheap-thrill addicts, who make up the bulk of the ring-siders—they get their own time in the glare of Wise's spotlight. A simple story, stripped right down to its trunks, but it's a B-movie with A-movie aspirations, calculating the odds in the zero-sum game in one movie's running time.

Two Flags West (1950) An odd foot-note in American history is the basis for this Western—during the Civil War, President Lincoln issued pardons to all Confederate POW's if they would volunteer for the Cavalry in the Indian Wars. When Col. Clay Tucker (Joseph Cotten) accepts this duty on behalf of his men, he is assigned to Camp Thorn, whose hobbled commander Maj. Henry Kenniston (Jeff Chandler) has had some common experience, having escaped from a Confederate Camp. On the surface, he welcomes the help from the Reb's, but deep down he resents them, especially Tucker's role in campaigns that have killed his brother, leaving a widow (Linda Darnell) that he dotes on and probably covets. The animosity Kenniston holds for Tucker is only the most simmering example of what is brewing between the blue and the grey troops stationed at Fort Thorn, New Mexico, a mere stop-over on the way to California. Such a remote position in the middle of nowhere is probably a safe bet for such troops as the reb's and the best-out-of-the-way Kenniston. They can be quietly ignored while the Army concentrates on the Civil War, out of sight, out of mind. But with Southern sympathizers who see it as an opportunity to bring California to the aid of the South, and a bitter vet in charge, who just barely keeps his anger under control, it should probably bear a bit more scrutiny. Wise does some channeling of John Ford in his elegiac compositions and asides, the cast boasts a fine collection of characters actors, but Cotten roots the movie with his Virginian background and his courtly manner.

Three Secrets (1950) The first words of the movie lay out the basic problem to be solved in the movie:"Mommy, when we gettin' home?" A plane crash in a high remote area near San Pedro looks like there are no survivors, but photo analysis shows that one 5 year old child has survived. As search parties start getting ready, it's revealed that little Johnny is adopted...so...who's the real parents? Well, considering the plane crashed on the way back to celebrating Johnny's birthday...

Well, it'll take the whole movie and lots of flash-back footage to find out. The three women who hear about it and are most concerned—tough newspaperwoman Phyllis "Phil'" Horn (Patricia Neal) gave up her child after a divorce, Susan Chase (Eleanor Parker) gave up her child after an indiscretion with a Marine and is now comfortably married to a lawyer, and showgirl Ann Lawrence (Ruth Roman) gave up her child because she was serving a prison stretch, for killing the rich bastard who threw her over. But, that's flashbacks, who's going to get the kid if and when they can get him off the mountain? If the formula sounds a lot like the previous year's Letter to Three Wives, that's because it's the same template and the same brand of soap. Even if you do figure out who the mother is, there's still the decision of who's going to take the kid. I smell noble gestures happening—that is, if the film follows formula. It does.

The House on Telegraph Hill (1951) Victoria Kowelska (Valentina Cortese) survives Bergen-Belsen with her friend Karin Dernakova who tells her of her son whom she sent away to San Francisco in the U.S. with her Aunt Sophia. Karin dies and when the camp is liberated, Victoria assumes her identity to get passage to the States. When she gets to New York, she finds out Aunt Sophia has died and the boy has gone to the legal guardian Alan Spender (Richard Basehart). Spender's legal team is suspicious of "Karin" as her son has inherited her Aunt's fortune. But, Spender is attracted to "Karin" and marries her within three days of meeting her and takes her back to Mandalay...er, the House on Telegraph Hill, where she must contend with the way Aunt Sophie's portrait stares at her...as well as Margaret (Fay Baker), who is son Christopher's care-taker, and takes to "Karin" the way Mrs. Danvers takes to Rebecca. On top of that, one of Spender's best friends is the very same Major, Marc Bennett (William Lundigan), who handled Victoria's papers when she was first liberated from Belsen. Fancy that!

Pretty soon, "Karin" is jumping at every shadow, every creaking floorboard, miffed at every slight, and starts to become very nosy about the place—like the playhouse that has a hole blown out of it..."by accident." And the time, she decided to take the car out...and the brakes failed...in San Francisco?

It's a stateside Rebecca, with the switched papers providing a good angle of how to introduce the woman-in-peril into the situation. And if you ever want to know where Meryl Streep got her "slovak" accent in Sophie's Choice, check out Valentina Cortesa in this film.

The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) Iconic sci-fi pic that managed to be just strange enough to be spiritual without having to explain itself. Edmund H. North's script (adapted from the 1940 Harry Bates story "Farewell to the Master") just assumed that any advanced civilization's technology would seem like magic to us (ala Clarke's Third Law). It's anti-nuke theme was somewhat off-set by it's Christ allegory under-pinnings: a human-appearing being from above comes to Earth with a "message," is killed and resurrected to give mankind a lesson in humility. That the alien--Klaatu (Michael Rennie)--walks among us under the guise of a "Mr. Carpenter" just nails the significance home.

Right from the get-go, The Day The Earth Stood Still announces its intention with a "spooky" theremin-laced score (by the brilliant Bernard Herrmann), quite at odds with its message of peace. Wise shows a global humanity surrounded by its current technology (radio, television, radar) spreading the news of an invader from space, which lands in the Mall area of a tourist-clogged Washington D.C. in Spring. Phalanxed by a wall of tanks and military might (with a larger crowd of tourists behind it) the alien presence reveals itself and is shot by a panicky soldier for its trouble. Before you can say "Kent State," the alien is taken to Walter Reed to be treated, observed and questioned, and the formal Klaatu--patient, curious, but with a hint of passive condescension--does his own analysis, escaping from the hospital and blending with the populace as "Mr. Carpenter"--taking a room at a boarding house, becoming involved with a widowed secretary (Patricia Neal)--it IS the '50's, after all--and her son, seeing humanity first-hand.

Meanwhile, his Enforcer, Gort, a lumbering, laser-cyclopsed, soft-metal robot stands guard over the saucer, turning his evil eye on any hint of aggression, without any regard to how much of the GNP was flushed to make those tanks. If Gort could laugh when he turned on his eye-light, he'd probably do it with glee.

The Day the Earth Stood Still is a classic film—a time-capsule, of a kind—from a different time and place and space that reminds, yes, with great power comes great responsibility--but there's always someone more powerful, who might take yours away, and make you stop and smell the fall-out.

Wise, in his first film for his Aspen Productions, was able to achieve an A-film look to his cheap B-film, thanks to "the Hoge lens" which gave his film a seemingly infinite depth of field, not unlike Citizen Kane.

Something for the Birds (1952) Anne Richards (Patricia Neal) is an environmentalist with the SPCC (The Society for the Preservation of the California Condor) wading her way through the halls and ballrooms of Washington D.C. to protect a habitat marked for natural gas drilling. She may be a fan of condors but the vultures of Capitol Hill are quite another matter. Luckily for her she meets one of the flock of D.C. wannabe's "Admiral" Johnnie Adams (Edmund Gwenn), a regular fixture at Washington functions—he's an engraver by trade, and never been in the Navy but someone thought he was an admiral at some point and he's never corrected the mistake for, in Washington, the impression of power is everything. Through Johnnie, she meets snaky lobbyist Steve ("Excuse me, while I peddle my influence...") Bennett (Victor Mature), who would like to help, but he's more interested in her "quid Pro quo." Oh, and one of his clients is gas company who wants the habitat's mineral rights. The movie is a nest of duplicity and glad-handering, but, as it's a comedy, it's all in good fun and good governance, one of those movies that doesn't shy away from the awful truth of institutionalized influence, but manages to make a statement for democracy in numbers. Why, it's almost fun to watch sausage being made. Neal is a joy to watch in a comedy role, and although Mature smiles a lot, he seems rather uncomfortable.

Destination Gobi (1953) One of those "untold stories" of World War II with an odd twist—this was about a consignment of "Saddles for the Navy." It's a long story. Chief Boatswain's Mate Sam McHale (Richard Widmark) is tasked by the Navy to lead a troop of meteorologists to the edge of Outer Mongolia to study weather patterns to help plan naval operations. McHale reluctantly accepts the assignment, trading in the sea and ships for desert and weather balloons and is aggrieved to spend months in the desert with a typical cadre of civillian wags (including Martin Milner, Darryl Hickman, Max Showalter, and Ross Bagdasarian and Earl Holliman, who isn't credited) who like to kid McHale about his dependence on chain-of-command and protocol. There is a side-benefit, however—a semi-friendly relationship with a tribe of Mongul nomads who pass through and take a grudging regard for the strangers in their midst—who have no interest in the grass of the oasis which is their staple. Both keep a wary eye for the Japanese zeros who are strafing their encampments, and after one such dust-up, the Navy Yanks find themselves in the same boat as the Monguls—crossing the brutal desert to try to get back to the ocean. The film plays like a Western merged with a war film, only with the Americans taking a much less xenophobic tact with their actions towards the indigenous people (although they still talk tough throughout and are ready with racial slurs for the Japanese enemy). It tries to play the movie for more laughs than it's worth, but it's ultimately a rather light study in culture clashes and cooperation.

So Big (1953) After two war films, Wise changes pace with an adaptation of Edna Ferber's already-twice-filmed Pulitzer Prize winning novel. Maybe the rigors of location shooting influenced him to make a domestic drama.

We meet Selina Peake (Jane Wyman) at a boarding school where she offers up to her house-mates her well-to-do father's saying: there are two kinds of people in the world—wheat and emerald; wheat people provide sustenance and emerald people are creative, providing the world beauty.

Dad dies, leaving her penniless. But, the family of a school-friend finds her a teaching position for a Dutch farming community. So, she moves from Chicago to the outskirts, where her buoyant ability to find the best in everything—"the cabbages are beautiful!" is one of her sentiments that makes the rounds—endears her to the community, and makes her a bit of a curiosity. She finds a room with the Poole family where she takes an interest in young Rolfe (Richard Beymer, who would work again with Wise, later, as a young adult)—who no longer attends school, tending, instead, the family farm—giving him books and encouraging him to pursue his interest in the piano and composing.

She meets and marries Pervus DeJong (Sterling Hayden), a truck farmer with a lot of land, but no luck raising crops and little education; she helps in the fields and with his "figurin'" at market. Soon, they have a child, Dirk, who, from birth, stretches out his arms, earning him the nickname "So Big." Life takes a turn for the worse when Pervus dies and Selina determines that she'll continue the farm, bucking tradition and raising eyebrows by taking her crops to market herself. Pervus' diligent farming and Selina's improvements eventually pays off and she's able to send Dirk to college to study architecture..

But, Dirk decides, after years of being a draftsman at a prestigious Chicago firm, to take a fast track to a higher income in sales and promotion, which makes him wealthy, but disappoints Selina, a wheat, who had hoped Dirk would become emerald, instead of (as she describes it) "a rubber stamp."

It's a story that runs parallel with Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons (which Wise edited...and helped butcher when Welles was out of the country) where worth and splendor of spirit have more to do with accomplishment than the accumulation of wealth. It's a cautionary tale that may seem out-of-fashion in these days...or even in the days of 1953...or 1923 when it was written. But, it's a nice little endorsement for hard work and gumption than the spoils of avarice.

Executive Suite (1954) John Houseman produces, Ernest Lehman writes and Wise starts out with a bang as executive Avery Bullard (in POV) walks out of a meeting with executives, rides the elevator to the lobby, writes out a cable that he's calling an emergency meeting at 6pm and dies of a stroke hailing a cab. Bullard is the "one man" of a one man corporation, Tredway Industries, and as business abhors a vacuum, the Vice Presidents immediately begin to position themselves for taking over the CEO job. Strategies are concocted, loyalties are tested, and backs are summarily stabbed in the power-grab between factions of a furniture-making company.

It all happens within a 24 hour period and the movie plays like a Grand Hotel of the board-meeting set. With an all-star cast of William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Frederic March (who acts like he's auditioning to play Richard Nixon), Walter Pidgeon, Paul Douglas, Louis Calhern, and Dean Jagger (with June Allyson and Shelley Winters in supporting roles), it is Nina Foch who walked away with an Oscar nomination for her work as Bullard's executive assistant. Wise keeps things moving along with just enough interference from unruly extras that you get the sense that it all isn't being played in a bubble. It is also one of the few movies that gets away without a music score of any kind—nor do you miss it.

Helen of Troy (1956) Wise moves from M-G-M to Warners for this Cinemascope "historical" epic based on Homer's "Iliad." Prince Paris of Troy (Jacques nee "Jack" Sernas) travels to Greece to negotiate a peace with the acquisitive nation, but is ship-wrecked in a storm, where he is rescued by Queen Helen of Troy (Rossana Podesta) and her maid-servant Andraste (Brigitte Bardot—yes, Bridgitte Bardot, just before she was to hit big with And God Created Woman) that would end up creating the war he was trying to avoid. Convinced by Helen that she's a slave to the Queen, Paris falls for her, thinking her the living embodiment of Aphrodite, but once all is revealed, the two are thrown together, and to keep Paris from being killed (after a fight with champion Ajax), they sail to Troy, where the citizenry aren't exactly thrilled once they find out who "the girl" is—the stolen wife of King Menelaus (Niall McGinniss).

Then, of course, the Greeks launch their "thousand ships," Hector (Harry Andrews) and Achilles (Stanley Baker) get into the act, and the Greeks leaving their little "gift" of a horse. What's different about this version is that it takes "the side" of Paris and Helen, even though their actions spell disaster for the glory that is Troy. It is a tough argument to make and no matter how ardent the two lovers may be (and Sernas and Podesta don't make the case very convincingly), one still sees them as selfish and irresponsible—the screenplay doesn't even try to blame it on the Gods, despite Paris' constant harkening to Aphrodite.

Wise (who also produced) shot at Cinecitta Studios in Rome and the film boasts an interesting international cast (save for the two leads) and Wise's compositions make full use of the Cinemascope frame, especially in the big crowd and battle scenes. The overall effect is a bit stilted and lifeless, a bit like the Trojan Horse itself, but doesn't hold as many surprises.

Only two reasons to watch this and that's Wise's Cinemascope landscapes and the only guy who could rival them for attention—Cagney. He's never been too comfortable on Westerns, but portraying a man of conflicting emotions (all of them at 100%) then Cagney's your man—Tracy wouldn't have made Rodock nearly as interesting—his posture like a braying rooster when he's full of himself or angry, and with his arms always cocked like he's about to start a fight or he should have reins in his hand. The story's hog-wash, but Cagney's the real deal.

This Could Be the Night (1957) Schoolteacher Anne Leeds (Jean Simmons) takes a part-time job in the evenings at "The Tonic", a Broadway nightclub run by former bootlegger Rocco (Paul Douglas) and Tony Amotti (Anthony Franciosa), his younger, hot-headed partner. Written by Isobel Lennart (based on short stories by Cornelia Baird Gross), This Could Be the Night plays like a Cinemascope black and white modern-dress version of Damon Runyon (Simmons had starred in Guys and Dolls two years earlier for Columbia) with the innocent pigeon finding her way amongst the nighthawks, while they're crackin' wise. The three leads have most of the screen-time, but the film is filled with nicely drawn out parts for the nightclub staff, who, one by one, start to affectionately call her "Baby"—although no one comes out and says it, it's because she's a virgin (a "greenhorn," "no runs, no hits, no errors" are some of the colorful verbal dancing they do around it) and in their world, that peculiarity is particularly rare...and to be protected. The character actors collected do some memorable work, particularly Joan Blondell as a stage mother, Neile Adams as her daughter, an aspiring cook and/or showgirl, J. Carrol Naish as the cook, Leon, Rafael Campos as busboy Hussein Mohammad, and particularly Julie Wilson as the house chanteuse/wise-gal, Ivy. Wise makes great use of the Cinemascope frame (Russell Harlan is the cinematographer) in a set-bound movie, and you can see him edging into musical territory—this is for M-G-M—with some nicely integrated musical numbers by Wilson and Adams. Surprisingly entertaining, with some rich dialog and clever blocking.

Until They Sail (1957) Based on a James A. Michener story and a Robert Anderson screenplay—both men served in the Pacific in WWII—Until They Sail is another "service love story" in Michener's vein. The four Leslie sisters—Anne "the iceberg" (Joan Fontaine), practical Barbara (Jean Simmons), Deliah (Piper Laurie) and debutante Evelyn (Sandra Dee)—of Christchurch, New Zealand are keeping the home-fires burning. Dad and Mum are dead, father being killed in the service, and Barbara's husband is serving in North Africa. They keep a map of the locations of the servicemen they've met and the battle-centers they read about in the papers. Deliah, with her beau out there somewhere gets into a hasty marriage with Phil or "Shiner" (Wally Cassell), but when he's shipped off, she ships out to the big city of Wellington, where she engages in a series of loose affairs. There's plenty of opportunity because it's just after Pearl Harbor and the Yanks are in town.

All the sisters find their own lives invaded by the war, as it affects the men in their lives, while they must cope with the after-effects whether "all's fair" or not. Love is found, love is lost and love is wasted in this soapish story of the collateral damage of war, where the lives of women are dictated and determined by men. Paul Newman makes a late entry as a love interest, but he doesn't appear all that happy to be there.

Run Silent Run Deep (1957) One of those general entertainment movies that manages to do so many things exceptionally well that one comes away grateful for the experience. Directed by Wise with a true sense of claustrophobia, the script by John Gay maintains a strict military accuracy while displaying a keen sense of drama, psychology and brevity. A psychological drama, a war film, a story of mystery as well as redemption, the film manages to pull everything off with a propulsive rhythm and fine performances throughout.

Produced by Hecht-Hill-Lancaster, Burt Lancaster the producer takes a back-seat to his star, Clark Gable, the older actor in one of his understated roles that takes into account his age. Gable's the flawed figurehead with shades of Ahab who finagles his way into the command of the S.S. Nerka patrolling the Pacific during World War II, having already lost one sub and and a frustrating convalescence at a desk-job.

Lancaster's exec Jim Bledsoe is torqued because Gable's Cmdr. "Rich" Richardson has pulled rank to get command—his command—and is now drilling the men to dive and shoot a torpedo within a record 35 seconds. The already suspicious crew starts to snarl about all this practice with nothing to show for it. Then a lucky strike convinces some of them the new Captain is golden, while the other half think he's out to torpedo their mission. Lancaster turns into a reluctant arbiter.

Run Silent, Run Deep is an intelligent tribute to the fighting services without resorting to jingoism, racism or choired flag-waving. The film-makers' respect for the professionalism under duress of sub-crews runs silent and deep.